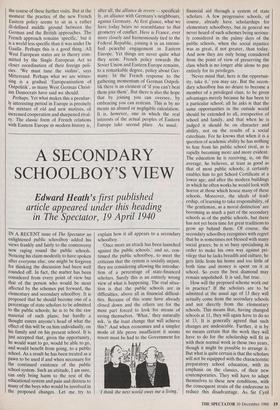

A SECONDARY SCHOOLBOY'S VIEW

Edward Heath's first published

article appeared under this heading in The Spectator, 19 April 1940

IN A RECENT issue of The Spectator an enlightened public schoolboy added his views frankly and fairly to the controversy now raging round the public schools. Noticing his claim modestly to have spoken after everyone else, one might be forgiven for thinking the discussion had been well rounded off. In fact, the matter has been considered from every point of view but that of the person who would be most affected by the schemes put forward, the elementary and secondary schoolboy. It is proposed that he should become one of a Percentage of state scholars to be admitted to the public schools; he is to be the raw material of such plans; but hardly a thought enters anyone's head of what the effect of this will be on him individually, on his family and on his present school. It is Just accepted that, given the opportunity, he would want to go, would be able to go, and would benefit from going, to a public school. As a result he has been treated as a pawn to be used if and when necessary for the continued existence of the public school system. Such an attitude, I am sure, can only bring harm to the rest of the educational system and pain and distress to many of the boys who would be involved in the proposed changes. Let me try to

explain how it all appears to a secondary schoolboy.

'Once more an attack has been launched against the public schools,' and so, con- tinued the public schoolboy, to meet the criticism that the system is socially unjust, they are considering allowing the introduc- tion of a percentage of state-financed scholars. Surely this is an entirely wrong view of what is happening. The real situa- tion is that the public schools are in difficulties, above all in financial difficul- ties. Because of this some have already closed down and the others are for the most part forced to look -for means of saving themselves. 'What,' they naturally ask, 'is the least change that will achieve this?' And when economies and a simpler mode of life prove insufficient it seems resort must be had to the Government for

'I think the next world owes me a living.' financial aid through a system of state scholars. A few progressive schools, of course, already have scholarships for elementary schoolboys, but in general we never heard of such schemes being serious- ly considered in the palmy days of the public schools, when the social injustice was as great, if not greater, than today. And now they are only being considered from the point of view of preserving the class which is no longer able alone to pay entirely for its privileges.

'Never mind that; here is the opportun- ity, take it,' you may say. But the secon- dary schoolboy has no desire to become a member of a privileged class, to be given advantages merely because he has been to a particular school; all he asks is that the same opportunities in the outside world should be extended to all, irrespective of school and family, and that when he is judged it should be on character and ability, not on the results of a social catechism. For he knows that when it is a question of academic ability he has nothing to fear from his public school rival, as is rapidly becoming more and more evident. The education he is receiving, is, on the average, he believes, at least as good as that of most public schools; it certainly enables him to get School Certificate at a lower age; and after the modern buildings in which he often works he would look with horror at those which house many of these schools. Moreover, the ideals of lead- ership, of learning to take responsibility, of 'the gentleman, as a moral distinction' are becoming as much a part of the secondary schools as of the public schools, but there has not yet been time for great traditions to grow up behind them. Of course, the secondary schoolboy recognises with regret that he is sometimes not blessed with many social graces; he is so busy specialising in order to make his own way against pri- vilege that he lacks breadth and culture; he gets little from his home and too little of both time and money is spent on it at school. So even the best diamond may remain unpolished. It is sad, but true.

How will the proposed scheme work out in practice? If the scholars are to be - admitted at the usual age of 13 they will actually come from the secondary schools and not directly from the elementary schools. This means that, having changed schools at 11, they will again have to do so at 13. It is generally agreed that such changes are undesirable. Further, it is by no means certain that the work they will have to do for the scholarship will fit in with their normal work in those two years, though it might be possible to arrange it. But what is quite certain is that the scholars will not be equipped with the characteristic preparatory school education, with its emphasis on the classics, of their new contemporaries. They will have to adapt themselves to these new conditions, with the consequent strain of the endeavour to reduce this disadvantage. As Sir Cyril Norwood has pointed out, to avoid these difficulties the whole of the present prepa- ratory school system, including the age of admission to public schools, would have to be altered. There is little sign of this happening at the moment.

But there is one objection to this scheme which cannot be avoided, though it may be ignored, and that is the effect it would have on the secondary schools in general. It would mean that the cream of their boys would be skimmed off.

Every school has its natural leaders and everyone knows how much the tone and the achievements of the school depend on them. The boys who would go off to the public schools would be the leaders in embryo of their houses, in work and in sport, in music and debate, and their loss would lower the standards of their school all round. Of course, I cannot speak for secondary school masters, but to say the least it would not be surprising if they objected strongly to losing their best boys in this way.

My last thoughts on this scheme will perhaps seem unimportant to the educa- tional theorist or the planner; to the person of imagination they may count above all else. They are these: to have to answer that one's father is a bus-driver, or a carpenter, perhaps; to know that one's parents cannot afford to travel to school functions, or to see them there, unhappy and ill at ease, and feel oneself shudder at a rough accent or a 'we was'; to be asked to stay with a school friend and to have to refuse for fear of asking him back to a humble villa; to have no answer to others' stories of travel in the holidays; worst of all, to see one's parents, who have made such sacrifices, grieve because they know one cannot have all the things one's associates have; that is what it will mean for a state scholar. Public schoolboys, we were told, 'are class- conscious and socially snobs'. Moreover, most boys are, consciously or unconscious- ly, cruel, and no matter how good a 'loving parent' the state may be it cannot alter these things; the pain and distress will be there, the strain of trying to reconcile home life and school life will take its toll of youthful happiness, and may leave its mark through life. Unlike Mark Bonham-Carter, I am no longer at school, but I am close enough to those years to know their thoughts; and at Oxford I've seen public and secondary schoolboys together; and, even in that home of tolerance, there iS the unhappiness which I am sure would exist, many times multiplied, were this scheme to be adopted in our schools. Our legislators will ignore it at their peril.

But though I may have disagreed with the public schoolboy over this particular proposal, we are, to judge from his article, in agreement on our ultimate aims, in his words 'to establish equality of opportunity in this country ... by abolishing inequality of education'. There is probably a job for both of us to do in trying to achieve that.

Previous page

Previous page