POSING ALL THE WAY TO THE BANK

Andrew Davidson examines the marketing

phenomenon of Chris Eubank, a boxer whose unpopularity is his greatest asset

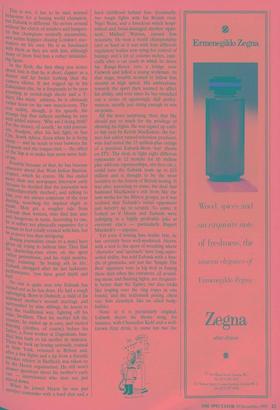

ONCE IN A while a sportsman comes along who is so unpopular as to be intensely marketable. This phenomenon, perceived to be modern but probably as old as the Colosseum, has rarely been so effectively exploited as by the boxer, Chris Eubank, super-middleweight champion of the world. He defends his title again in Manchester on Saturday, live on satellite television, the fourth of a much-trumpeted eight-fight, i6-million deal with Rupert

Murdoch's Sky. It would not be an exag- geration to say that most boxing fans in Britain are hoping that he loses.

Given the fact that British world cham- pions in any sport are rare indeed, and tend to be revered whatever their personal failings, it takes a remarkable man to over- come the sports fan's traditional jingoism. But Eubank, whose high-domed forehead, little-girl lisp and dandy demeanour make him a distinctive figure, works hard at it. His blunt disdain for boxing and his appar- ent desire to do the very minimum in the ring to win each fight raise strong feelings among the sport's followers. Ask them their opinion of Eubank and the response

is usually pithy: he is, in the argot of East End gyms, a 'prat' and a `wanker'. Why? Perhaps it is the monocle, jodli. purs and spats (the 28-year-old Eubank,

believe it or not, likes to dress like all

Edwardian gent out on an elephant shoot), or his arrogant, blunt obstructiveness In interview, or simply the fact that he is prob- ably no more than just an averagely god boxer — when he can be bothered. Bat somehow Eubank manages to convey a

message that couldn't be more offensive to the true boxing enthusiast. The sport, he says, is for blood-thirsty mugs. 'If I found

two million poundth tax-free in the road I, would be out of thith bithnith tomorrow,

he announced recently. He is not going t°

bleed all over the canvas for anyone, 3 novel approach to a sport in which the capacity to suffer, as well as to inflict suf- fering on others, is vital. Simply put, he refuses to play the game. Some of this is clearly clever marketing. Eubank's fly, Romford-based manager, Barry Hearn, is no stranger to manipulat- ing working-class dreams and aspirations. Hearn, who likes to describe himself as

'king of the Cis', was one of the main movers in the transformation of snooker from a shady pastime for villains and layabouts (who else has all afternoon t°

practise?) into a top-rating television Wort' The twist now is that he is no longer ereat. ing heroes. In Eubank — whose back- ground (poor, black, south London) is II° different from most other boxers' — he has helped create something that gets right up working-class noses. That, in turn, helPs sell tickets.

Yet perhaps Hearn should not be given too much credit, as the increasingly eccea- tric Eubank is clearly a broken law OW himself. Despite living with wife and tv'i° children in a modern mansion in Hove, he is frequently to be seen cruising Savile Ro.v or Jermyn Street adding to his extra0r.(11- nary wardrobe, or driving his motorbike round London, dropping in on his acqual°- tances in the media. He still, for instance, regularly visits the offices of Esquire 111 Soho, some three years after it did a covert feature on him. He is also a frequent goes at middle-class media parties. This is not, it has to be said, normal behaviour for a boxing world champion, but Eubank is different. He moves around Without the clutch of minders and hangers- 011 that champions normally accumulate, and seems happier chasing London's star- makers on his own. He is as fascinated with them as they are with him, although nt. ally of them find him a rather intimidat- ing figure.

In the flesh, the first thing you notice about him is that he is short, dapper as a dancer and far better looking than the camera allows. If not togged up in his Edwardian chic, he is frequently to be seen Prowling in crotch-high shorts and a T- shirt; like many athletes, he is obviously rather keen on his own muscle-tone. The real oddity, though, is his speech, the strange lisp that inflects anything he says With added naivety. 'Why am I doing thith? !or the money, of courth,' he told journal- ists, deadpan, after his last fight, in Sun CitY, South Africa. Even when he is being Sharp — and he tends to veer between the eloquent and the tongue-tied — the effect of the lisp is to make him seem more ludi- crous.

Possibly because of that, he has become Obsessive about that West Indian fixation, respect, which he craves. He has ended more than one newspaper interview early because he decided that the journalist was Mthrethpectfully drethed', and talking to hurl, You are always conscious of the eyes • arting, searching insult. for implied slight or Men get a rougher ride from Eubank than women, who find him sexy and dangerous in turns. According to one, he is rather too physically expansive for a woman to feel totally relaxed with him, but he is never less than intriguing. . Boxing journalists (male to a man) have given up trying to fathom him. They find his chattering-class views on the sport irather pretentious, and his regal noncha- lance irritating. 'In boxing ath in life,' Eubank shrugged after his last lacklustre Performance, 'you have good dayth and No one is quite sure why Eubank has turned out as he has done. He had a tough upbringing. Born in Dulwich, a child of his Widowed mother's second marriage and ,surrounded by nine siblings, he learnt to nox the traditional way, fighting off his elder brothers. Then his mother left the el:3.11114Y, he ended up in care, and started tfhieving (clothes, of course) before his ather, a Ford worker at Dagenham, bun- dled him back to his mother in America. There he took up boxing seriously, trained ul New York, returned to Britain and, after a few fights and a tip from a friendly bsnooker referee in Sheffield, was taken on Y the Hearn organisation. He still won't neuSwer questions about his mother's early interviewers who dare are just stared down. When he joined Hearn he was just allOther contender with a hard chin and a hard childhood behind him. Eventually, two tough fights with his British rival, Nigel Benn, and a knockout which hospi- talised and brain-damaged another oppo- nent, Michael Watson, earned him notoriety. He won a world championship (not as hard as it was with four different regulatory bodies now vying for control of boxing) and a lot of column inches, espe- cially after a car crash in which he drove his Range-Rover into a bridge near Gatwick and killed a young workman. At that stage, trouble seemed to follow him around at high speed. His ambivalence towards the sport then seemed to affect his ability, and ever since he has stretched out a series of agonisingly dull perfor- mances, usually just doing enough to win on points.

All the more surprising, then, that Sky should pay so much for the privilege of showing his fights. He was signed up earli- er this year by Kelvin MacKenzie, the for- mer Sun editor turned television producer, who had noted the 15 million-plus ratings of a previous Eubank-Berm 'war' shown on ITV. The deal, to fight eight different opponents in 12 months for £.6 million plus add-ons (sponsorships, site-fees etc.), could earn the Eubank team up to £10 million and is thought to be the most lucrative in the history of British boxing. It was also, according to some, the deal that hastened MacKenzie's exit from Sky (he now works for the Mirror group), as it was realised that Eubank's initial opponents just weren't up to scratch. To some, it looked as if Hearn and Eubank were indulging in a highly profitable joke at everyone else's — particularly Rupert Murdoch's — expense.

Yet even if boxing fans loathe him, he has certainly been well-marketed. Hearn, with a nod to the sport of wrestling where 'character' and 'spectacle' have long super- seded ability, has sold Eubank with a bun- dle of gimmicks, not just the 'Simply The Best' signature tune (a big deal in boxing these days when the entrances, all pound- ing music and flashing lights, are frequent- ly better than the fights), but also tricks like leaping over the ring ropes in one bound, and the trademark posing, chest out, fists clenched, like an oiled body- builder.

None of it is particularly original. Eubank shares his theme song, for instance, with Chancellor Kohl and a well- known fizzy drink, to name but two (he also has the motto inscribed on his Mer- cedes). As a package it gives him a distinct image, but recently, combined with his lacklustre performances, it has only served to infuriate the crowds to new heights of derision. The Eubank pose, especially, in a sport which can enthral with its grace of movement, is now seen as the perfect defi- nition of what he is about: stasis. No won- der boxing fans scream 'Get on with it!' at him.

Yet the more he is disliked, the more interest there is in seeing him get beaten, as the grinning Hearn never fails to point out. Eubank is not simply the best, he is a conundrum. No one knows if he will ever recover the form that saw him do the unthinkable — permanently scramble the brains of an opponent — or if the very fact that he has done that means that he will never give his all again. Some think he just won't fight properly because he is now frightened of getting his face cut.

Eubank certainly has his detractors. The whisper in the sport is that, for all his games of bluff-and-brag with the media, he is no smarter than the average boxer who earns a huge bundle and spends it as fast as he gets it. There are the stories of Eubank's lorry (he fell in love with a large American HGV, bought it, shipped it over and then failed his HGV driving test, so it sits in the drive of his home; occasionally he climbs in and toots the horn), and of the shopping expeditions by Concorde to get his wife a dress, the thousands spent on clothes every month.

Perhaps it is all tabloid tosh, but some who know him think that underneath the braggadocio Eubank is probably rather a confused figure, in need of advice but too headstrong to let anyone, even Hearn, close enough to guide him. As he says, if he's lucky he will get out of the sport at the end of his eight-fight deal with a few mil- lion in the bank and his brains and face intact.

Previous page

Previous page