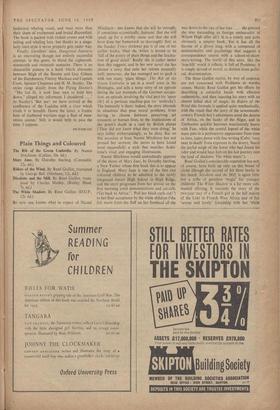

Plain Things and Coloured

The Rib of the Green Umbrella. By Naomi Mitchison. (Collins, 10s, 6d.)

By now one knows what to expect of Naomi

Mitchison : one knows that she will be strongly, if sometimes eccentrically, humane; that she will speak up for a worthy cause and that she will have done her homework so thoroughly that, as the Sunday Times reviewer put it of one of her earlier books, what sht, writes is bound to be 'full of the poetry of plain things and the fascina- tion of good detail.' Really she is rather better than this suggests, and in her new novel she has chosen a story that suits her talents unusually well; moreover, she has managed not to pack it with too many 'plain things.' , The Rib of the Green Umbrella is set in a small town in the Montagna, and tells a tense story of an episode during the last moments of the German occupa- tion, an episode involving the vital part (or 'spare rib') of a partisan machine-gun (or `umbrella'). The humanity is there; indeed, the story abounds in situations that pose moral problems, from having to choose between preserving art treasures or human lives, to the implications of the priest's death in a raid by British planes ('They did not know what they were doing,' he says rather embarrassingly, as he dies), But on this occasion at least Naomi Mitchison has not pressed her sermon; she seems to have found most successfully a style that matches Ardiz- zone's vivid and engaging illustrations.

Naomi Mitchison would undoubtedly approve of the theme of Mary Jane, by Dorothy Sterling, a New Yorker whose first book this is to appear in England. Mary Jane is one of the first two coloured children to be admitted to the newly integrated Junior High School in High Ridge, and the story progresses from her arrival on the first morning amid demonstrations and cat-calls ('Go back to Africa!', 'Pull her black curls out!') to her final acceptance by the white children ('she felt warm from the fluff on her forehead all the way down to the tips of her toes . . . she guessed she was succeeding as foreign ambassador at Wilson High after all') It is a timely and quite obviously a sincere book. Yet it has all the flavour of a glossy mag, with a compound of sentimentality and psychology that suggests a correspondence course with a school-of-short- story-writing. The world of this story, like the `true-life' world it reflects, is full of Problems; it is simply devoid of moral, as distinct from politi- cal, discrimination.

The three Guillot stories, by way of contrast, are not concerned with Problems or worthy causes. Mainly Rend Guillot gets his effects by describing a colourful locale with effective authenticity, and then injecting his story with an almost lethal shot of magic. In Riders of the Wind this formula is applied quite mechanically, with the result that the story of the seventeenth- century French boy's adventures amid the deserts of Africa, on the banke of the Niger, and in Tiinbuctoo quickly becomes wearisomely heavy with Fate, while the central legend of the white mare puts in a perfunctory appearance from time to time, laden down with fine writing (Calvi, 'very near to death' from exposure in the desert, 'heard the joyful neigh of the horse who had found his rider and would bear him on his last journey into the land of shadows. The white mare!').

Rend Guillot's considerable reputation has not, of course, been built up only on this brand of cliché (though the second of his three books in this batch, Nicolette and the Mill, is again little but a trifle of pointless 'magic' for younger children). The White Shadow is a far more sub- stantial offering. lt recounts the story of the two-year stay of a French girl in the hill station of the Lobi in French West Africa and of her 'serene and lovely' friendship with her 'white

shadow,' her sister-shadow, the simple native girl Yagbo (as was foretold by the snake-charmer in Marrakesh). For all Guillot's Conrad-like in- dulgences and the unfailing Gallic polish of his style (`sensitively translated' by Brian Rhys); for all that Galaire the doctor is 'a man of visions' and Tournoy the customs officer is a 'poet of a kind' and Bruce is an animal-man who 'gave you insight into the forest's secrets': for all this load of disabilities, the story is unusual and un- expectedly compelling. Guillot is himself an odd amalgam of visionary, poet of a kind and animal- man and he knows the African world in which his stories are set. Moreover, as, in this book at least, he doesn't lean heavily on the element of African magic, and even seems to some extent willing to expose its crudities, he leaves himself free to introduce Frances to a remote jungle- world dominated by the language of tom-toms and the cries of wild animals. Back at school in Bordeaux, one can sympathise with her sense that 'only her body seemed to be present in the classroom' and hear 'the secret thrill in the voice of the girl' as she speaks to the others of 'a land far away on the edge of the world.'

BORIS FORD

Previous page

Previous page