Cinema

Clara's Heart (`15', Warner West End)

One sob too many

Hilary Mantel

Two months ago, in a café near Leices- ter Square, I was eavesdropping while two elderly ladies planned their afternoon cine- ma trip. It was impossible to work out exactly what they were going to see, but they were clearly aiming at an afternoon of the most pleasurable emotional wallowing. `Tissues disintegrate nowadays,' one of them said. She picked up a handful of paper napkins from the table. 'These will do to wipe my eyes.'

I picture them, this week, sobbing in each other's arms at the Warner West End; declaring that napkins will not do, they should have brought a paper tablecloth. When Joseph Olshan's novel came out in 1985, it was well-liked, but something has gone wrong in its translation to the screen; Clara's Heart repeatedly crosses the fine line which divides the moving from the maudlin, and finally rubs out the line altogether.

Clara (Whoopi Goldberg) is a maid working in a hotel in a Jamaican holiday resort. Leona (Kathleen Quinlan) and her husband Bill (Michael Ontkean) are a wealthy young couple who have taken a holiday to try to recover from the cot-death of their baby daughter. Leona is paralysed by depression, and only Clara can talk her into believing that life is worth living. The family arrange to take Clara back to their mansion near Baltimore; here, in her idiosyncratic way, she begins to take over the household and make herself indispens- able. At first her presence is resented by the adolescent son David (Neil Patrick Harris), a round-faced, bespectacled boy who is young for his age and mildly bullied by his classmates. Clara divines that David is blaming himself in some obscure way for the cot-death, and sets out to win him over. She is a woman of unsparing honesty and lio respecter of persons; she approaches the boy in a spirit which is protective yet equal, and when the parents' marriage begins to break up, she becomes the one person he can rely on for a straight answer. The other adults, whilst spouting psycholo- gical jargon to show they care, put their own needs before the needs of the baffled and rootless child.

If Clara is not such a saintly pain-in-the- neck as she might be, this is because Whoopi Goldberg endows the character with great dignity and with an edged but gentle humour which is very attractive. Goldberg has not had a good part since she played Celie in The Colour Purple, yet she has twice as much screen presence as most white actresses of her generation. But what is very odd is the notion of black culture that the film purveys. Clara takes a room in Baltimore, to give her somewhere to go on weekends off, and there finds a ghetto of compatriots, many of whom she knows from her earlier life; she takes David to mix with them, to be dazzled by their warmth, to be clutched to their jiggling bosoms, and to pick up a patois like none you've ever heard. The black community seem to live in a condition of permanent fiesta. Were you to put this all-singing all-dancing crew in a British film, you'd pretty soon get a fatwa from Brent Coun- cil. Before these scenes, which seem to have strayed in from another film entirely, you would call Clara's Heart nothing worse than slow, bland and obvious; after them, you would say that the director Robert Mulligan has completely lost his grip on the enterprise.

But it snuffles ever onwards. Clara, we know, has some dark secret in her past; she's involved with something so terrible that no one can quite bring themselves to voice it. And when the revelation comes, it is jaw-dropping awful, so awful that it has to be narrated, for it can't be shown in flashback; left with no time to assimilate it, the viewer can only emit a protesting squeak from behind her sodden handker- chief. It is a colossal misjudgment of tone. and a betrayal of the weepy-fan. The director has invited us to a banquet of delicious melancholy, furnished us with the necessary table-linen, then placed a sev- ered finger in the After Eight mints.

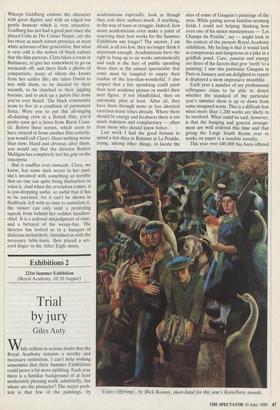

Previous page

Previous page