Before the revolution

Helen Osborne

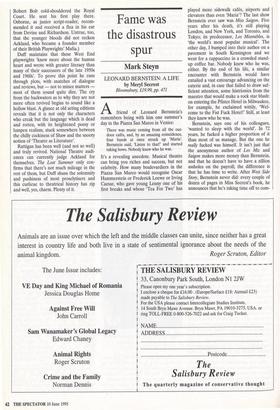

THE LOST SUMMER by Charles Duff Nick Hem Books, £18.99, pp. 288 Own up if you have never seen a play called The Holly and the Ivy, which reperto- Frith Banbury, aged 32, as Joseph Surface in The School for Scandal at the Oxford Playhouse ry companies used to trundle out every Christmas during my childhood. Go to the back of the class if you have never heard of its author, Wynyard Browne, a minimalist of great 'charm' and 'poetic' naturalism, a master of 'sensitive' writing, a man compas- sionately tolerant and warm of heart. When the boyos stormed Sloane Square in the late Fifties, audiences decided that they could get enough charm, sensitivity, warm hearts etc. at home. The poetic naturalists were given the heave-ho.

'Quiet plays from a quiet man,' is how Charles Duff describes Browne and his work in The Lost Summer, a curate's egg of a book which attempts a persuasive nudge to the proposition that If one realises that Edith [Evans] is only interested in Edith; if one accepts that fact, one can be quite fond of her.

Banbury began as a light-weight actor and spent much of the war in the cut-throat campery of Intimate Revue. 'Prissy' was how John Gielgud described him. Soon he found his natural home as a director at H. M. Tennent and Duff's account of this legendary institution and its Godfather, Binkie — 'I owe it all to Hitler' — Beaumont is as good and amusing as you will get. Banbury states that, 'Theatre peo- ple today are fifty times more educated and culturally efficient [whatever that means] than Binkie ever was,' which is nonsense. I have met two and a half producers who could be described as educated. Most of them can't even spell Kulture. Stretching hyperbole, he compares Beaumont to Diaghilev; what God gave stage-struck Binkie was a sharp business nose and a hugely talented pool of actors, untempted by television and voice-overs, prepared to slog out long West End runs.

As well as Browne, Banbury championed the maverick Rodney Ackland. N. C. Hunter, Rattigan, Whiting and Emlyn Williams all craved the Beaumont-Banbury connection. (It is untrue, incidentally, that

there was far more vitality in the English theatre before the arrival of the angry young men and the Royal Court revolution than is generally acknowledged.

The author was born in 1950, so his evi- dence is based on texts and pictures, reviews and hearsay, but despite his altogether amiable and fluent advocacy, the Both Banbury's grandfathers were crooks. His father was a blustery Admiral with `too much respect for the Navy to want this boy to go into it'. This boy, financed by a doting Jewish mother, turned out to be a life-long pacifist, a happy homosexual, short on melancholy and introspection, but doughty, and adroit with actresses of a certain age. As he learnt from Sybil Thorndike: Robert Bolt cold-shouldered the Royal Court. He sent his first play there. Osborne, as junior script-reader, recom- mended it and received a flea in his ear from Devine and Richardson. Untrue, too, that the younger bloods did not reckon Ackland, who became a founder member of their British Playwrights' Mafia.) Duff maintains that these West End playwrights 'knew more about the human heart and wrote with greater literacy than many of their successors of the late 1950s and 1960s'. To prove this point he runs through plots, with snatches of dialogue and reviews, but — not to mince matters — most of them sound quite dire. The cry from the backwaters as to why they are not more often revived begins to sound like a hollow blast. A glance at old acting editions reveals that it is not only the characters who creak but the language which is dead and rotten, with its heightened poesy or lumpen realism, stuck somewhere between the chilly cockiness of Shaw and the snooty notion of 'Theatre as Literature'.

Rattigan has been well (and not so well) and truly revived. National Theatre audi- ences can currently judge Ackland for themselves. The Lost Summer only con- firms that there's not much mileage in the rest of them, but Duff shuns the solemnity and pushiness of most proselytisers and this curlicue to theatrical history has zip and well, yes, charm. Plenty of it.

Previous page

Previous page