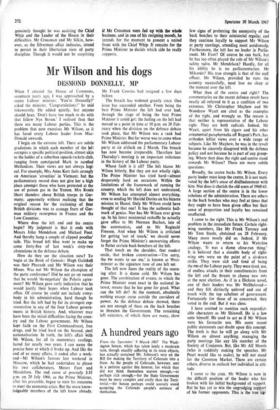

Mr Wilson and his dogs

DESMOND DONNELLY, MP

When I entered the House of Commons, seventeen years ago, I was approached by a senior Labour minister. 'You're Donnelly?' asked the minister. 'Congratulations!' he said lukewarmly. He added quietly, lest anyone should hear, 'Don't have too much to do with that fellow Nye Bevan.' I realised then that there are many Labour parties. This is the problem that now exercises Mr Wilson, as it has faced every Labour leader from Mac- Donald onwards.

I begin on the extreme left. There are subtle gradations in which each member of the left occupies a specific political position, almost akin to the ladder of a suburban squash-rackets club, ranging from constipated Mark to rarefied Methodism. Their views are not always logi- cal. For example, Mrs Anne Kerr feels strongly on American 'atrocities' in Vietnam; but the parliamentary record does not give her a high place amongst those who have protested at the use of poison gas in the Yemen. Mrs Renee Short thunders about British troops in Ger- many; apparently without realising that the original reason for the stationing of four British divisions was to assuage fears of Ger- man military resurgence in France and the Low Countries.

Where does the left end and the centre begin? My judgment is that it ends with Messrs John Mendelson and Michael Foot. And thereby hang a couple of clipped poodles' tails. This broad left bloc went to make up some forty-five of last week's sixty-two abstentions in the defence debate.

How do they see the situation now? To begin at the Book of Genesis: Hugh Gaitskell was their Pharaoh and Mr Wilson was their Moses. Was not Mr Wilson the champion of the party conference? Did he not go on record that he would 'de-negotiate' the Polaris agree- ment? Mr Wilson gave early indication that he would justify their hopes when Labour took office. Of course he could not include every- body in his administration, hard though he tried. But the left had by far its strongest rep- resentation in any of the four Labour govern- ments in British history. And, whatever may have been the initial difficulties facing the coun- try and the Labour government, Mr Wilson kept faith on the First Commandment, free drugs, and he tried hard on the Second, steel nationalisation. In truth, the left's affair with Mr Wilson, for all its momentary coolings, lasted for nearly two years. I can name the precise hour at which it broke up. And like the end of so many affairs, it ended after a week- end—Mr Wilson's famous lost weekend in Moscow, which he had undertaken to please his two collaborators, Messrs Foot and Mendelson. The end came at precisely 3.35 p.m. on 20 July 1966, as the Prime Minister, after his preamble, began to state his measures to meet the economic crisis. But the more know- ledgeable members of the left knew already.

Mr Frank Cousins had resigned a few days before.

The breach has widened greatly since. One issue has succeeded another. From being the best Prime Minister the left had ever had; through the stage of being the best Prime Minister it could get; the feeling on the left had moved to a point in time at 10 p.m. on 28 Feb- ruary when the division on the defence debate took place, that Mr Wilson was a rank bad Prime Minister. But far worse was to come when Mr Wilson addressed the parliamentary Labour party at six o'clock on 2 March. The breach has now become irreparable. Therefore last Thursday's meeting is an important milestone in the history of the Labour party.

Whose fault is it all? The left blame Mr Wilson bitterly. But they are not wholly right. The Prime Minister has tried hard—almost desperately hard on occasions. Within the limitations of the framework of running the country, which the left does not understand, Mr Wilson has attempted almost everything, even to sending Mr Harold Davies on his bizarre mission to Hanoi. Only Mr Wilson could have thought of that one! It has the authentic hall- mark of genius. Nor has Mr Wilson ever given up. In his latest ministerial reshuffle he actually gave office to Mr Norman Buchan, late of the communists, and to Mr Reginald Freeson. And when Mr Wilson is criticised for getting 'out of touch,' we should never forget the Prime Minister's unswerving efforts to flatter certain back-benchers of the left.

That touch on the shoulder, that modest smile, that broken conversation—'l'm sorry, the PM wants to see me,' is known at West- minster as the signature tune of one left he.

The left now faces the reality of the morn- ing after. It is damn cold. Mr Wilson has gone. The combination of events, to which the Prime Minister must react in the national in- terest, means that he has gone for good. What can the left do? At the moment, absolutely nothing except curse outside the corridors of power. As the defence debate showed, there are not enough of them on the back benches to threaten the Government. The remaining left ministers, of which there are many, show few signs of preferring the anonymity of the back benches to their ministerial regalia; and they continue loyally to support Mr Wilson at party meetings, attending most assiduously. Furthermore, the left has no leader in Parlia- ment. Mr Foot? Of course he can bark, but he has too often played the role of Mr Wilson's safety valve. Mr Mendelson? Hardly, for all his ability he is no parliamentarian. Mr Mikardo? His true strength is that of the staff officer. Mr Wilson, provided he runs the country successfully, need lose no sleep at the moment over the left.

What then of the centre and right? The commentaries on the recent defence revolt have

nearly all referred to it as a coalition of two extremes. Mr Christopher Mayhew and Mr Woodrow Wyatt are cited as the examples of the right, and wrongly so. The reason is that neither is representative of the Labour right. They are both radicals. Indeed, Mr Wyatt, apart from his cigars and his other ornamental paraphernalia off Regent's Park, has orthodox leftist views over a wide range of subjects. Like Mr Mayhew, he was in the revolt because he sincerely disagreed with the defence policy and not because he is part of any group- ing. Where then does the right and centre stand towards Mr Wilson? These are more subtle questions.

Broadly, the centre backs Mr Wilson. Every party leader must keep the centre. It is not moti- vated by the left's sense of disillusionment with him. Nor does it cherish the old scars of 1960-61. A large section of the centre is in the lower echelons of the administration. There are others in the back benches who may feel at times that they ought to have been given office but their sense of proportion and loyalty has remained unaffected.

I come to the right. This is Mr Wilson's real problem in the immediate future. Certain right- wing members, like Mr Frank Tom ney and Mr Tom Steele, abstained on 28 February. Many more nearly did so. Indeed, if Mr Wilson wants to return to his Waterloo analogy, 'It was a damn close-run thing.' It is believed that a sizeable body of right- wing Nes were on the point of a sit-down strike. They were sick and tired of being the PHI of the Labour party. They were tired, too, of endless attacks in their constituencies from the left and the threats to choose new MPS at the next election. As if in a Dickens novel, one of their leaders was Mr Wel'beloved- and they felt distinctly unloved and out of touch with the top echelons of government. Fortunately for those of us concerned, they voted in the end. But it was close.

I have omitted to mention such unpredict- able characters as Mr Shinwell. He is a law unto himself. He used to act as if Mr Wilson were his favourite son. His more recent public statements cast doubt upon this concept. The truth is that he will go along with Mr Wilson on almost anything, managing the party meetings like any life member of the Society of Conjurers. But, like Mr Alf Morris (who is suddenly making the speeches Mr Peart would like to make), he will not stand for the Common Market. There are certain others, diverse in outlook but individual in atti- tude.

I come to the crux. Mr Wilson is now in the difficult position of the leader who has broken with his initial background of support. But he has yet to win the ungrudging support of his former opponents. This is the true sig:. nificance of the right' s current discontent. Furthermore, on the two crucial issues of British politics—the economy and the Common Market—he will face increasingly bitter oppo- sition from the left if he does, what should he do? In certain cases, such as that of Mr Shinwell on the Market and some trade union nws on a new Incomes and Prices Bill, he will also lose some right-wing support. There- fore he must retain the centre and win the enthusiastic support of the rest of the right. Off the Westminster stage, but thundering out- side the box office, there is also Mr F. Cousins. He should not be forgotten, nor should any other important trade union leader. After all, these gentlemen own the real estate of the Labour party. They also own the annual party conference.

Mr Wilson's main opposition is always events. His success and even survival will de- pend upon the speed and flexibility of his re- action to them. But that is not enough any longer. Having got thus far, the question is: Will he become a big enough man to have around him big men who speak frankly and yet can prove loyal? Or will he try to do it all himself, which will prove impossible?

Previous page

Previous page