Exhibitions

Landscapes from a High Latitude: Icelandic Art 1909-1989 (Barbican Concourse Gallery, till 8 April)) Keith Grant: Paintings of the Arctic and the Desert (Crane Kalman, till 17 March)

Northern lights

Giles Auty

0 ne of the sadder aspects of the 1988 Venice Biennale for me was the paucity of visitors to the pavilions of little-considered nations, almost hidden sometimes among the trees of the exhibition gardens. Three days after the opening of the Biennale the visitors' book in the Uruguayan pavilion recorded only two signatures. Similarly I saw no one else on the two visits I made to the Icelandic pavilion. Most critics prob- ably expect less from the art of small, physically isolated nations, whereas para- doxically I hope for more: to find truly original talents, for instance. So-called Zeitgeist is notoriously poor at travelling over long stretches of water so that Icelan- dic art manages in general to retain a refreshing individuality and disregard for the more facile, magazine-borne forms of international modishness.

For visitors, at least, Iceland offers the fascination of remoteness laced with stir- ring history. Of course, for those who live in this northern fastness the realities may seem altogether more prosaic and uncom- fortable. Only a tiny proportion of Europe's second biggest island is cultivated or inhabited. Three hundred thousand people live largely round the coastal fringe. The centre of the island contains the volcanoes, glaciers, lakes and geysers which give Iceland its unique topography; not surprisingly, Icelandic art is rooted firmly in the physical. Clear, unpolluted air encourages brilliant lichens. Summer days are almost endless and the characteristic lowness of the sun promotes the dark, fathomless blues of the sea. The current Barbican exhibition comprises 70-odd works by 25 artists. Oil paint is the medium chosen by most to celebrate the physical toughness of their terrain. There are mov- ing landscapes and seascapes but no still- lives, interiors or portraits. The beautiful tapestries of Asgerdur Buadottir, woven from local wool and pony hair, similarly celebrate an external world. What pleasant relief we discover at the Barbican from the gloomy introspection of so much of the art which stems from richer, more spoiled and comfortable countries. The impetus lead- ing to the present exhibition was formed by an unlikely combination of present and former staff of Brighton Polytechnic plus the nurturing hand of the Icelandic govern- ment. Considerable credit is reflected thereby on both institutions.

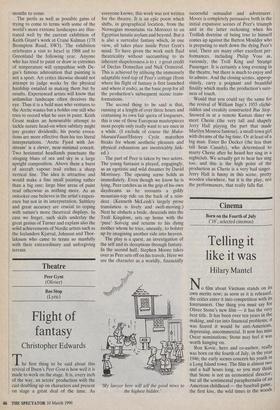

Having written already this year about the great Danish traditions in landscape painting, I am delighted to notice a new gallery, Arcticus (56 Fulham Road, SW3), has opened to deal in Nordic art as a fresh addition to such established outlets as Bury Street Gallery in St James's. The present show at Arcticus features works by such as Kyhn, Ring, La Cour, Skovgaard and Michael Ancher. Arcticus will be showing works from other Nordic nations in the `Summer Night at Thingvellir', 1931, by Johannes Kjarval, at the Barbican months to come.

The perils as well as possible gains of trying to come to terms with some of the world's more extreme landscapes are illus- trated well by the current exhibition of Keith Grant's work at Crane Kalman (178 Brompton Road, SW3). The exhibition celebrates a visit to Israel in 1988 and to Greenland the following year. Anyone who has tried to paint or draw in extremes of temperature will sympathise with De- gas's famous admonition that painting is not a sport. Art critics likewise should not attempt to judge works by the physical hardship entailed in making them but by results. Experienced artists will know that unfamiliar landscape often deceives the eye. Thus it is a bold man who ventures to the Arctic wastes but a bolder one still who tries to record what he sees in paint. Keith Grant makes an honourable attempt to tackle nature head-on when subtlety might pay greater dividends; his poetic evoca- tions are more effective than his too literal interpretations. 'Arctic Fjord with Jet- stream' is a clever, near-minimal conceit. Two horizontal headlands punctuate the stinging blues of sea and sky in a large upright composition. Above them a burst of aircraft vapour trail etches a sharp vertical line. The idea is attractive and would make a fine small painting rather than a big one; large blue areas of paint read otherwise as nothing more. As an onlooker one believes in the artist's experi- ence but not in its interpretation. Subtlety and great accuracy are crucial to coping with nature's more theatrical displays. In case we forget, such skills underlay the great genius of Turner and explain also the solid achievements of Nordic artists such as the Icelanders Kjarval, Johnson and Thor- laksson who came to terms so manfully with their extraordinary and unforgiving terrain.

Previous page

Previous page