Musick

Addison's admonitions

Peter Phillips

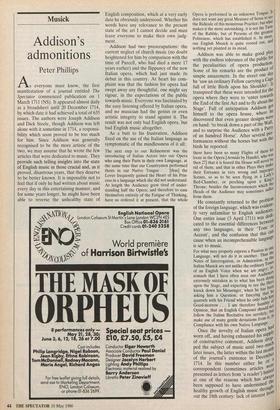

As everyone must know, the first manifestation of a journal entitled The Spectator commenced publication on 1 March 1711 (NS). It appeared almost daily as a broadsheet until 20 December 1714, by which date it had achieved a total of 635 issues. The authors were Joseph Addison and Dick Steele, though Addison was left alone with it sometime in 1714, a responsi- bility which soon proved to be too much for him. Since Addison was generally recognised to be the more artistic of the two, we may assume that he wrote the few articles that were dedicated to music. They provide such telling insights into the state of English music in those crucial and, as it proved, disastrous years, that they deserve to be better known. It is impossible not to feel that if only he had written about music every day in this entertaining manner, and for some years longer, he might have been able to reverse the unhealthy state of English composition, which at a very early date he obviously understood. Whether his words have any relevance to the present state of the art I cannot decide and must leave everyone to make their own judg- ment.

Addison had two preoccupations: the current neglect of church music (no doubt heightened for him by comparison with the time of Purcell, who had died a mere 17 years earlier) and the flippancy of the new Italian opera, which had just made its debut in this country. At heart his com- plaint was that the fashion for opera had swept away any thoughtful, one might say rigour, in the expectations of the public towards music. Everyone was fascinated by the easy listening offered by Italian opera, and no musician had the genius or even artistic integrity to stand against it. The result was not only bad English opera, but bad English music altogether.

As a butt to his frustration, Addison fixed on the use of the Italian language as symptomatic of the mindlessness of it all:.

The next step to our Refinement was the introducing of Italian Actors into our Opera who sang their Parts in their own Language, at the same time that our Countrymen performed theirs in our Native Tongue . . . [thus] the Lover frequently gained the Heart of his Prin- cess n a language which she did not understand. At length the Audience grew tired of under- standing half the Opera; and therefore to ease themselves entirely of the Fatigue of Thinking, have so ordered it at present, that the whole Opera is performed in an unknown Tongue. It does not want any great Measure of Sense to see the Ridicule of this monstrous Practice; but what makes it the more astonishing, it is not the Taste of the Rabble, but of Persons of the greatest Politeness, which has established it. In short, our English Musick is quite rooted out, and nothing yet planted in its stead. Addison was able to make good Play with the endless tolerance of the public for the peculiarities of opera production. Some of his remarks are the product of simple amazement. In the street one day he 'saw an ordinary Fellow carrying a Cage full of little Birds upon his Shoulder'. It transpired that these were intended for the opera where they were to 'enter towards the End of the first Act and to fly about the Stage'. Full of anticipation Addison got himself to the opera house, where he discovered that even greater designs were on hand: 'to break down a part of the Wall, and to surprise the Audience with a PartY of an hundred Horse'. After several per- formances without the horses but with the birds he reported: there have been so many Flights of them let loose in the Opera [Armida by Handel, who vies then 27] that it is feared the House will never be rid of them; and that in other Plays they make their Entrance in very wrong and imprope! Scenes, so as to be seen flying in a LAY,: Bed-Chamber, or perching upon a Killr Throne; besides the Inconveniences which e Heads of the Audience may sometimes suffer from them. He constantly returned to the problern of the foreign language, which was evident- ly very unfamiliar to English audiences.- One entire issue (3 April 1711) was dedi cated to the essential differences between any two languages, in their 'Tone nr Accent', and the confusion that this Call cause when an incomprehensible language is set to music. For what may properly express a Passion in °Ile Language, will not do it in another. Thus the Notes of Interrogation, or Admiration, in the as Italian Musick are not unlike the ordinarY T°°. of an English Voice when we are angrY; 1/1; somuch that I have often seen our Audience extremely mistaken as to what has been ri,g upon the Stage, and expecting to see the H„ knock down his Messenger, when he has be asking him a Question; or fancying that .r! quarrels with his Friend when he only bids In Good-morrow . . . I am therefore huroblY Opinion, that an English Composer should riu bti; follow the Italian Recitative too servilelY1 in make use of many gentle deviations from it, Compliance with his own Native Language. d Once the novelty of Italian opera hap, worn off, and having exhausted his atiP1),; of constructive comment, Addison drciti; ped the subject of music until two -luneth later issues, the latter within the last Mot r of the journal's existence in Decenwea 1714. In this number either he or e correspondent (sometimes articles weld presented as letters from 'a reader') finites at one of the reasons which has alle been supposed to have undermined healthy growth of English music througu, out the 18th century: lack of interest forw' Potential patrons.

I have often wondered to hear Men of good Sense and good Nature profess a Dislike to Musick, when at the same time, they do not scruple to own, that it has the most agreeable and improving Influences over their Minds. [In the former article he hit on another equally important cause for worry:] I could heartily wish there was the same Application and Endeavours to cultivate and improve our Church-Musick, as have been lately bestowed on that of the Stage . . . Musick, when thus applied, raises noble Hints in the Mind of the Hearer, and fills it with great Conceptions. It strengthens Devo- tion and advances Praise into Rapture.

Church music also had, and possibly could Still have, through a steady sense of direc- tion and rejection of ephemera, the knack of forming the backbone to strong native schools of composition.

Previous page

Previous page