HOWE NOT TO DO IT

`Consensus', argues Noel Malcolm, has

little to do with Europe, and even less to do with Sir Geoffrey Howe

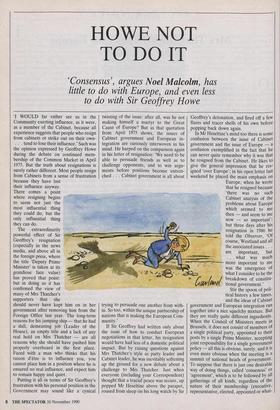

`I WOULD far rather see us in the Community exerting influence, as it were, as a member of the Cabinet, because all experience suggests that people who resign from cabinets or strike out on their own- . . . tend to lose their influence.' Such was the opinion expressed by Geoffrey Howe during the debate on continued mem- bership of the Common Market in April 1975. But the truth about resignations is surely rather different. Most people resign from Cabinets from a sense of frustration because they have lost their influence anyway.

There comes a point where resigning begins to seem not just the most influential thing they could do, but the only influential thing they can do.

The extraordinarily powerful effect of Sir Geoffrey's resignation (especially in the news media, and above all in the foreign press, where the title 'Deputy Prime Minister' is taken at its grandiose face value) has proved that point: but in doing so it has confirmed the view of many of Mrs Thatcher's supporters that she should never have kept him on in her government after removing him from the Foreign Office last year. The long-term reasons for his jumping ship — that he had a dull, demeaning job (Leader of the House), an empty title and a lack of any real hold on Mrs Thatcher — are all reasons why she should have pushed him properly overboard in the first place. Faced with a man who thinks that his raison d'être is to influence you, you cannot place him in a position where he is ensured no real influence, and expect him to remain happy and quiet.

Putting it all in terms of Sir Geoffrey's frustration with his personal position in the Government may sound like a cynical twisting of the issue: after all, was he not making himself a martyr to the Great Cause of Europe? But as that quotation from April 1975 shows, the issues of Cabinet government and European in- tegration are curiously interwoven in his mind. He harped on the comparison again in his letter of resignation: 'We need tb be able to persuade friends as well as to challenge opponents, and to win argu- ments before positions become entren- ched . . . Cabinet government is all about trying to persuade one another from with- in. So too, within the unique partnership of nations that is making the European Com- munity.'

If Sir Geoffrey had written only about the issue of how to conduct European negotiations in that letter, his resignation would have had less of a domestic political impact. But by raising questions against Mrs Thatcher's style as party leader and Cabinet leader, he was inevitably softening up the ground for a new debate about a challenge to Mrs Thatcher. Just when everyone (including your Correspondent) thought that a trucial peace was secure, up popped Mr Heseltine above the parapet, roused from sleep on his long watch by Sir Geoffrey's detonation, and fired off a few flares and tracer shells of his own before popping back down again.

In Mr Heseltine's mind too there is some confusion between the issue of Cabinet government and the issue of Europe — a confusion exemplified in the fact that he can never quite remember why it was that he resigned from the Cabinet. He likes to give the general impression that he res- igned 'over Europe'; in his open letter last weekend he placed the main emphasis on Europe, when he wrote that he resigned because `there was no such Cabinet analysis of the problems about Europe which seemed to me then — and seem to me now — so important'; but three days after his resignation in 1986 he told the Observer, 'Of course, Westland and all the associated issues . • • are important, but . . . what was much more important to me was the emergence of what I consider to be the ca44_, breakdown of constitu- 9( tional government.' Stir the spoon of poli- tical history a few times, and the ideas of Cabinet government and European integration run together into a nice squelchy mixture. But they are really quite different ingredients. When the Council of Ministers meets in Brussels, it does not consist of members of a single political party, appointed to their posts by a single Prime Minister, accepting joint responsibility for a single government policy — all this is obvious, surely, and it is even more obvious when the meeting is a summit of national heads of government. To suppose that there is just one desirable way of doing things, called 'consensus' or 'agreement', which is to be followed by all gatherings of all kinds, regardless of the nature of their membership (executive, representative, elected, appointed or what- ever), is a recipe for needless confusion.

And to be served up this confused claim by Sir Geoffrey and Mr Heseltine is doubly confusing, since they are both, in different ways, such unlikely champions of consen- sus in the first place. Michael Heseltine built his reputation as a potential future Prime Minister not on the notion that he was a consulter and an agreer, but on the idea that he was a `charismatic', swash- buckling figure, the acceptable face of conviction politics. His occasional out- bursts, his mace-waving and combat jacket-flaunting, were forgiven him by a public which expected a certain amount of flamboyance in any leader-from-the-front. Those who experienced his administrative style, his civil servants and the Chiefs of Staff whom he summarily re-organised, will confirm that he is certainly not one of life's consensus-seekers.

And oddly enough, the last six months or so have seen him reverting to type even when discussing Europe — putting his combat jacket back on again, so to speak, and talking more and more about Britain going further into Europe in order to 'fight' more effectively for national self-interest. So it came as a greater surprise when, in his Open letter last weekend, he changed back into 'consensus' civvies, not only dropping the talk about 'fighting' and the defence of independent self-interest, but implicity cri- ticising others for using it. 'You cannot praise the Germans for the role they have played in Nato, and then imply that they are fighting for some cause different from our own,' he wrote. Oh, can't you? Then what was Mr Heseltine doing when he wrote in the Daily Telegraph on 5 April: Let there be no misunderstanding. Coun- tries are members of Nato and of the Community for one reason above all others: membership is in their self- interest'?

The oddity of Sir Geoffrey Howe waving the flag of Cabinet consensus, on the other hand, is at first less obvious; but in reality it is even more gross. When historians come to analyse what happened to Cabinet government during the 1980s, they will find that in almost every process of taking key decisions away from the full Cabinet meet- ings Sir Geoffrey was intimately involved. There are very few discussions of Govern- ment decisions by full Cabinet,' he blithely told a reporter in 1984. That was after the decision to ban trade unions at GCHQ had been presented as a fait accompli to the Cabinet by a small group consisting of him, the Prime Minister, Mr Heseltine and Lord Whitelaw. The most important shift of power away from Cabinet in the early Thatcher years — in effect, the origin of all her Cabinet-sidestepping manoeuvres was the hiving off of crucial economic decision-making to secret Cabinet commit- tees in order to carry through Sir Geof- frey's economic policies, which would nev- er have survived regular discussion, let alone majority voting, in full Cabinet. One senior minister of that time has summed up his experience of Cabinet membership: `We really met for ceremonial purposes. All power, all decision-taking, all policy formation occurred between No. 10 and No. 11. It seemed to mostly occur late at night, as decisions unmade in the evening were often concluded by the morning. Thatcher and Howe could not have been closer. We were merely told what had been decided.'

It is not intolerably cynical, then, to - suggest that Sir Geoffrey Howe would never have resigned over the uncomprom- ising combativeness of the Prime Minister, so long as she had been engaged in combat on his side, for his preferred set of objec- tives. Similarly one cannot imagine that Mr Heseltine would have lost many hours' sleep over the observance of constitutional niceties, so long as any railroading of Cabinet had resulted in his preferred policy going through. But here the parallel be- tween the two H-men breaks down; for although it is quite clear what Mr Hesel- tine's preferred policy was in 1986 (a European consortium for Westland Heli- copters), it is far from clear what would satisfy Sir Geoffrey 'I am not a Euro- idealist or federalist' Howe's inchoate longings. Asked about the next stage of monetary union on Sunday 25 October, he told Brian Walden: 'The Prime Minister and I agree absolutely that it would be quite foolish . . . at today's meeting in Rome, to commit ourselves to finality, to a conclusion, to a date resolving that kind of question.' Four days later he was offering, as one reason for his resignation, the Prime Minister's failure to make that 'quite fool- ish' commitment, a failure which he now described as 'isolating ourselves unduly'.

Sir Geoffrey's friends will point out, of course, that he was speaking under duress in that Walden interview — the painful duress of Cabinet government. For months he had been forced to use these wooden phrases, to conceal his real views; and what irked him above all was that while he made the effort to be wooden to oblige the Prime Minister, the Prime Minister made no attempt to make her own expressions of opinion more wooden in order to oblige him. But then why should she? She has been concerned first to resist the 'bounc- ing' tactics of the other heads of govern- ment, and secondly to strike a strong policy stance on Europe which will distinguished the Tory Party from the new Euro-me- tooism of the Labour front bench.

Mrs Thatcher's unkinder critics have compared her to the log lady', a mad, and obsessive woman in television's latest cult soap opera who wonders round every- where clutching a pet log. But there has been nothing very wooden about her be- haviour: if she was the log lady, then it was Sir Geoffrey who was the log. Last week, by accident rather than design, she finally dropped it — on her foot. The stumble this caused will not put her off her stride for long.

Previous page

Previous page