The Fourth Man

Auberon Waugh

God's Apology: A chronicle of three friends Richard ingrams (Deutsch £5.50) There is the difficulty in reading a friend's book that one hears his voice on every page and measures the written word beside one's knowledge of its author. This is especially true, of course, with novels, where one searches for characters or episodes which may form part of shared experience and looks rather nervously for a judgement on them. Ingrams's book should present no such difficulty, being a chronicle of friendship between three historical persons, two Of whom are dead — Hugh Kingsmill and Hesketh Pearson — the third— Muggeridge — very much alive, as they say. Other historical persons — Shaw, Frank Harris, Enid Bagnold, Belloc, Beerbohm-Tree, Desmond MacCarthy, Alfred Douglas, Chesterton, D.H. Lawrence — flit through the pages, and there seems no reason, at first glance, why one should not treat the book as just another of those trips down memory lane which are growing more popular week after week at the present time as our country's future becomes more dismal. Lots of people have lived, moved around a little, then died, and there is no earthly reason why Ingrams should not write about them. Not everything he writes has to be about his own friends. Why, then do I find Myself wincing and blushing at this description of Frank Harris?

'But his personality was unstable and the effects of fame, and the failure to distalguish between love and lust, politics and literature, or fact and fantasy, in the end Parted him from reality. From about the tarn of the century he became increasingly unhinged and subject to delusions of grandeur and persecution mania.' It. may be true that one of Ingrams's few -artier published works, Harris in Wonierland (a thriller, written with Andrew Dsmond) is a thinly disguised biographical Audy of his great contemporary Richard but Frank Harris, after all, is a horoughly documented historical person; a 'nari would have to be dangerously in hinged and subject to delusions of gran deur and persecution mania to suppose that Ingrams was getting at him with this description. We read that Hesketh Pearson — at that time a 'great fan of Harris's — used to send the madman parcels of Old Etonian ties to his home in France. Ingrams has never sent me a parcel of Old Etonian ties to my French retreat. In fact the only parcel he has ever sent me here contained this book. Perhaps . . . but no, that way madness lies.

These suspicions are prompted in part by a curiosity, which will be shared by many, about Ingrams's reasons for writing the book, in part by a suspicion, which is likely to be less widely shared, that in writing about these three amiable but distinctly minor literary figures the author is in fact — most uncharacteristically — writing about himself.

Plainly this was not his intention, but it is the irritating way of critics to spot things which they are not invited to spot. In a slightly awkward Introduction Ingrams explains how he was brought to Kingsmill's work by their common friend, Muggeridge; how he found it difficult to reconcile Muggeridge's picture of Kingsmill as the flamboyant, recklessly humorous, impenetrably wise teacher and friend with the picture derived from his books and Michael Holroyd's biography; how the search led him to Hesketh Pearson, the biographer, whose robust, unorthodox views and excellent wit he found immediately congenial; and how he determined to produce a record of their friendship which would also serve as a monument to Hugh Kingsmill, the least known but most influential of the three, whose talents were dissipated in the fugitive art of conversation.

Yes, yes, I see all that, but why? Anybody who has ever written a book will know that it is a tremendous sweat, there is very little money in it, very little prospects of acclaim. and Ingrams does not even begin to explain why he should feel this tremendous pietas towards two dead men he never met and a third, still living, who is perfectly capable of speaking and writing for himself: 'This book is about three friends — Malcolm Muggeridge, Hugh Kingsmill and Hesketh Pearson. But there is a fourth friend involved, too — myself.'

Cryptic or whimsical as this sentence may seem, I am convinced it holds the key. The first three friends are easily described but the Fourth Man is more elusive. Let us examine the easiest part first.

Hugh Kingsmill, brother of the Catholic apologist and ski fanatic Arnold Lunn, son of Sir Henry Lunn, founder of the travel agency (there is a delightful portrait of this eccentric figure, as well as of the other brother, Brian, among the book's many give-away prizes), was a delightful, wise, funny man who achieved no success whatever as a writer. This was partly because he refused to associate himself with the fashionable political causes of the time — it is a wonderful thing to read an account of the literary life of the 1930s which simply does not mention Isherwood, Auden, Spender, MacNeice, Day-Lewis or any of the wretched galere — partly because his writing lacked the quality of robust excellence which might have enabled it to confound the prevailing literary establishment.

All of Kingsmill's books are now out of print, I think, and I have read none, although I would like to read his critical biography of D.H. Lawrence, which, by Ingrams's account, sounds very sensible. Most of Kingsmill's views appear eminently sound — as a result, he acquired the reputation of an embittered debunker — but I think he made too much of his distinction between the Will and Imagination, where the Will is represented by men of action, Dawnists or political Utopians, the Imagination by true poets and mystics. A better distinction would surely be between Populists — those who submerge their own perceptions in some popular movement, comprehensive philosophy or political ideal — and Individualists or idiots who follow their own perceptions and processes of discovery regardless of everyone else.

Johnson, one of Kingsmill's greatest heroes, could scarcely have been less of a mystic or more of an Individualist, while Wordsworth, another hero, might have been vaguely mystical in his approach to nature, but was the first Dawnist of all in his approach to the French Revolution. The trouble was that Kingsmill combined the postures of wit and mystic (which don't go very well together) with those of mystic and sceptic, which don't go together at all. Although all his perceptions and intuitions were sound, his attempts to rationalise them ended in a muddle of whimsy and paradox. But he was plainly a delightful fellow to have known, and survives in the memory of his friends.

Pearson was an altogether more formidable character. He shared with Kingsmill a passionate devotion to Shakespeare, but what drew them together in the first place wlas a shared enthusiasm for the ludicrous Frank Harris. Kingsmill was the first to see the error of this, and he led Pearson away from it just as he was later to lead Pearson away from Dickens, Arnold and Shaw; and Muggeridge (who wept on hearing of D.H. Lawrence's death in 1930) from his infatuation with the humourless pseudo-mystic whom Kingsmill describes as 'not a conscious charlatan, but he had an instinct for exploiting the wide areas of imbecility in the English upper classes'. Pearson was a funny, violent, tough and rather tragic man his son Henry went mad and died in Spain fighting for the Communists much influenced by Kingsmill.

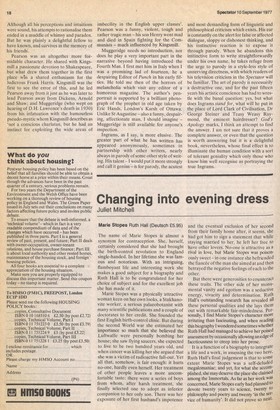

Muggeridge needs no introduction, nor does he play a very important part in the narrative beyond having introduced the Fourth Man. I first met him in Italy when I was a promising lad of fourteen, he a despairing Editor of Punch in his early fifties. He told me then of the horrors of melancholia which visit any editor of a humorous magazine. The author's penportrait is supported by a brilliant photograph of the prophet in old age taken by Eric Hands, London's Karsh of Ottawa. Unlike St Augustine also a funny, despairing, affectionate man, I should imagine Muggeridge is still available for anyone's inspection.

Ingrams, as I say, is more elusive. The greater 'part of what he has written has appeared anonymously, sometimes in partnership with other writers, nearly always in parody of some other style of writing. His talent I would put it more strongly and call it genius is for parody, the acutest and most demanding form of linguistic and philosophical criticism which exists. His ear is constantly on the alert for false or affected dialogue, sloppy or dishonest thinking, and his instinctive reaction is to expose it through parody. When he abandons this instinctive form to write straightforwardly under his own name, he takes refuge from the urge to parody in a style-less style of unnerving directness, with which readers of his television criticism in the Spectator will be familiar. The art of parody is necessarily a destructive one, and for the past fifteen years his artistic conscience has had to wrestle with the banal question: yes, but what does lngrams stand for, what will he put in the place of Lord Clark of Civilisation, Dr George Steiner and Teasy Weasy Raymond, the eminent hairdresser? God's Apology marks, I think an attempt to find the answer. I am not sure that it proves a complete answer, or even that the question is worth answering but it is a delightful book, nevertheless, whose final effect is to illuminate the human condition with a sort of tolerant geniality which only those who know him well recognise as portraying the true Ingrams.

Previous page

Previous page