Impressionism all' Italiana

J. A. Gere

THE MACCHAIOLI: ITALIAN PAINTERS OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY by Norma Broude

Yale University Press, £35, pp. 346

Somewhere in every large Italian city is a Galleria d'Arte Moderna, but its tran- quillity is rarely disturbed by even the most inquisitive tourist, and it is little visited by the Italians themselves. In the Parisian counterpart, the Musee d'Orsay, the pan- demonium is hardly less than in the railway station that the building originally was. The contrast reflects the indisputable pre- eminence of the French school in the history of 19th-century painting, a pre- eminence that has so coloured our view of the period that only recently has it come to be recognised that other European coun- tries produced schools of painting of more than merely local significance.

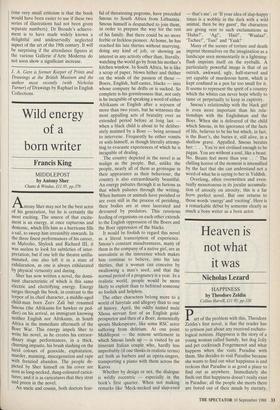

The 'Macchaioli' were a group of Italian painters born in the 1820s and 1830s and active mostly in Tuscany. Like their Eng- lish contemporaries, the Pre-Raphaelites, they were in revolt against a moribund academic tradition. Both artistic revolu- tions began — as artistic revolutions always do — as affirmations of 'truth to nature', but they interpreted 'truth' in very differ- ent ways. They shared an awareness of the art of the Italian quattrocento, but for the Macchaioli this was not a source of quaint mediaeval accessories but an example of formal directness and simplicity of treat- ment. They were essentially realists, and their closest links were with France: chron- ologically, as in style and technique, they come between the School of Barbizon and the Impressionists, and similarly their main interest was in landscape. In the literal sense of the words, their art was impressionistic and photographic, con- cerned above all with rendering the instan- taneous effect on the eye of forms dis- solved in light. In such snapshot sketches as Sernesi's Pavilion at the Cascine (pl. 13) and Roofs in Sunlight (pl. 14), or Vito d'Ancona's Portico (pl. 16), or Abbati's Cloister (pl. 17), all datable c. 1860-1, the forms are rendered without outlines, in terms solely of the gradation of colour and tone; and Dr Broude demonstrates, by juxtaposing well chosen examples, the ex- tent to which the Macchaioli technique, of plein air sketching was influenced by photography.

The name of the group is generally explained as derisive in origin (like 'Whig' and 'Tory' and indeed 'Impressionist') from the sense of the word `macchia' as a smudge or shapeless spot, in allusion to their impressionist technique. It was first applied to them in print in this pejorative sense, but, as Dr Broude shows, the artists themselves understood the word in its alternative meaning, of the broadly painted effect of a rough sketch, and by extension the fundamental structure of a landscape composition or what Constable called the 'chiaroscuro of nature' — the essential element of dramatic unity that holds the composition together. The Mac- chaioli must thus be seen in the context of the revolution of taste initiated by Const- able, which required that the finished full-scale painting, though produced in the studio, should have the lively handling and apparent spontaneity and artlessness of the first sketch from nature. The history of 19th-century landscape was dominated by the problem of reconciling spontaneity of handling with monumentality of scale. The Macchaioli technique was appropriate only to the small sketch, and on the whole they wisely kept their pictures small. When they were tempted to enlarge a composition the result is as often as not a blown-up sketch in which the macchia technique has itself become a mannerism. (One of the most important facts about any picture is its size, and it is a particular merit of this admirable book that the dimensions of every work illustrated are stated in the caption).

This was not exclusively a school of landscape. The Macchaioli remained faith- ful to the ideal of realism, but this took different forms: Lega's poetic domestic genre; Fattori's military subjects with pat- riotic and political overtones — needless to say, they were all fervent supporters of the Risorgimento — and scenes of peasant life in the `campagna romana' tradition of Charles Coleman; Signorini's city land- scapes, including a remarkable view of a drab street in Leith dominated by an enormous advertisement for Rob Roy whisky, and subjects of social-realistic con- tent, treating with Zolaesque brutality the squalor of the madhouse, the brothel and the prison; others gravitated towards the `aesthetic' English rather than French- orientated type of landscape developed in Italy by Giovanni Costa, who, though closely associated with the group and in sympathy with many of their aims, cannot be considered as fully part of it.

The Macchaioli were aware of contem- porary developments in French painting. One of Degas's best-known portraits is of the art critic Diego Martelli, the eloquent expounder and defender of their ideas, and he was also on terms of friendship with Fattori and Signorini. If the group failed to produce anyone of the stature of Degas or Monet or Renoir, they were always in touch with what was most vital in the art of their time.

Outside Italy the Macchaioli are little known. A high proportion of their best work is still in Italian private collections, and almost all the literature on them is in Italian. Dr Broude has written the first full-length study of the subject in English, and it is impossible to believe that it will not remain the definitive work. She has examined with exemplary thoroughness every aspect of the movement — its stylistic antecedents and later critical for- tunes, and the development of each indi- vidual artist. There is a full and intelligent index and what is clearly a complete bibliography. The book is beautifully pro- duced in the style that we have come to expect from the Yale University Press, with 91 colour plates of admirable quality and 306 illustrations, in black and white `Roofs in Sunlight' by Raffaello Sernesi, c. 1860-1 (one very small criticism is that the book would have been easier to use if these two series of illustrations had not been given separate numbers). Dr Broude's achieve- ment is to have made widely known a delightful and undeservedly neglected aspect of the art of the 19th century. It will be surprising if the attendance figures at the various Gallerie d'Arte Moderna do not soon show a significant increase.

J. A. Gere is former Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum and the author most recently (with Nicholas Turner) of Drawings by Raphael in English Collections.

Previous page

Previous page