CHESS

Campo's bull

Raymond Keene

Every so often the World Chess Fed- eration President, Florencio Campomanes, issues a circular letter to the Fide faithful. The latest, sent out in August, is a remark- able document. In it Campo threatens to report Kasparov to the Fide General Assembly for his abrasive remarks about the leadership of the world body.

Perhaps Kasparov's often expressed fear that Fide may try to ban him, as they did with Grandmaster Quinteros last year, or declare him persona non grata, as they did with Calvo, is now becoming more real.

Whatever the reasons for these bannings, it is ominous that Fide has never done it before and now there have been two in just one year.

Certainly, the machinery for dealing with Kasparov may soon officially exist, since the same Fide encyclical contains David Anderton's proposals for the Fide ethics code. Although this has many useful points, its main objectionable feature is an attempt to gag the chess press. Anderton's justification in the Fide documents is armed with lengthy extracts from, believe it or not, the British Public Order Act of 1936. I am constantly baffled that chess officials should want to play at politics like this, quoting Acts of Parliament designed to suppress riotous behaviour rather than infringements at the chessboard. Mean- while, Kasparov has been doing what these bureaucrats cannot — playing great chess.

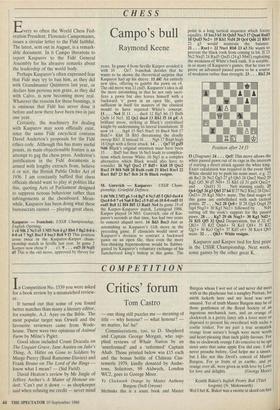

Kasparov — Ivanchuk: USSR Championship; English Opening. 1 c4 Nf6 2 Nc3 e5 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 g3 Bb4 5 Bg2 0-0 6 0-0 e4 7 Ng5 Bxc3 8 bxc3 Re8 9 f3 This position arose twice in the Kasparov-Karpov cham- pionship match in Seville last year. In game 2 Karpov now chose 9 . . . e3. 9 . . . exf3 10 Nxf3 d5 This is the old move, approved by theory for years. In game 4 from Seville Karpov avoided it with 10 . . . Qe7. Ivanchuk decides that he wants to be shown the theoretical surprise that Kasparov had up his sleeve. 11 d4! An entirely new idea, offenng to gambit the pawn on c4. The old move was 11 cxd5. Kasparov's idea is all the more astonishing in that he not only sacri- fices a pawn but also leaves himself with a backward 'e' pawn in an open file, quite sufficient in itself for masters of the classical mould to have rejected White's concept. 11 . . Ne4 If 11 . . . dxc4 12 Bg5 h6 13 Bxf6 Qxf6 14 Ne5. 12 Qc2 dxc4 13 Rbl f5 14 g4! A brilliant mvoe, striking at Black's centralised knight by undermining its lateral foundations. If now 14 . . . fxg4 15 Ne5 Nxe5 16 Bxe4 Nc6 17 Bxh7+ Kh8 18 Rb5 threatening the deadly swoop Rh5. If instead 16 . . . Ng6 17 Bxg6 hxg6 18 Qxg6 with a fierce attack. 14 . . . Qe7 15 gxf5 Nd6 Black's original intention must have been 15 . . . Bxf5 but then 16 Ne5 leads to complica- tions which favour White. 16 Ng5 is a complex alternative which Black would also have to consider. 16 Ng5 Qxe2 17 Bd5+ Kh8 18 Qxe2 Rxe2 19 Bf4 Nd8 20 Bxd6 cxd6 21 Rbel Rxel 22 Rxel Bd7 23 Re7 Bc6 24 f6 Black resigns.

M. Gurevich — Kasparov: USSR Cham- pionship; Griinfeld Defence.

1 d4 Nf6 2 NS g6 3 c4 Bg7 4 Nc3 d5 5 Qb3 dxc4 6 Qxc4 0-0 7 e4 Na6 8 Bet c5 9 d5 e6 10 0-0 exd5 11 exd5 Re8 12 Bf4 Bf5 13 Rad 1 Ne4 In game 19 of the Karpov-Kasparov match, Leningrad 1986, Karpov played 14 Nb5. Gurevich, one of Kas- parov's seconds at that time, has had two years to concoct aliquid novi. 14 Bd3 Bxc3 Just as astonishing as Kasparov's 11th move in the preceding game. If classicists would snort at Kasparov's decision to contract a backward pawn on an open file, then even the more free-thinking hypermoderns would be flabber- gasted by Kasparov's voluntary exchange of his fianchettoed king's bishop in this game. The

point is a long tactical sequence which forces, equality. 15 bxc3 b5 16 QxbS Nxc3 17 Qxa6 Bxd3 18 Qxd3 Ne2+ 19 Khl Nxf4 20 Qc4 Qd6 21 Rfel 21 g3 would maintain the balance. 21 . . . Rxel+ 22 Nxel Rb8 23 a3 He wants to prevent the black rook from coming to b4. If 23 Nc2 Nxd5 24 Rxd5 Qxd5 (24 g3 Nb61) exploiting the weakness of White's back rank. It is notable, in so many of Kasparov's games, that he tries to prove an advanced passed pawn to be a source of weakness rather than strength. 23 . . . Rb2 24 Position after 24 f3 f3 (Diagram) 24 . . . Qe5! This move allows the white passed pawn out of its cage in the interests of starting a direct attack against the white king. Exact calculation was required in the event that White should try to push his main asset, e.g. 25, d6 Re2 26 Nc2 0g5 27 g3 Qh5 28 Qxe2 Nxe2 29 Kg2 Qf5 30 d7 N14+ 31 Khl (if 31 gxf4 Qxc2± and . . . Qxdl) 31 . . . Ne6 winning easily. 25 Qe4 Qg5 26 g3 Qh5 27 h4 If 27 Nc2 Rxc2 28 Qxc2 Qxf3 + 29 Kg1 Nh3+ mate. The final stages of this game are embellished with such tactical points. 27 . . . Ne2 28 Qe8+ If 28 Qg4 Qxg4 29 fxg4 Nxg3+ 30 Kgl Ne2+ followed by . . Nd4 cutting off the rook's support for the passed pawn. 28 . . . Kg7 29 d6 Nxg3+ 30 Kgl. Nd2+ 31 Kn Qf5 32 Qxe2 Desperation, but if 32 d7 Qh3+ 33 Kf2 Qxh4+ 34 Ke3 Qf4+ 35 Kf2 Qg3+ 36 Ke3 Qg5+ 37 Kd3 c4+ 38 Kxc4 Qb5 mate. 32 . . . Qh3+ White resigns.

Kasparov and Karpov tied for first prize in the USSR Championship. Next week, some games by the other great K.

Previous page

Previous page