New developments in dance

Jan Murray

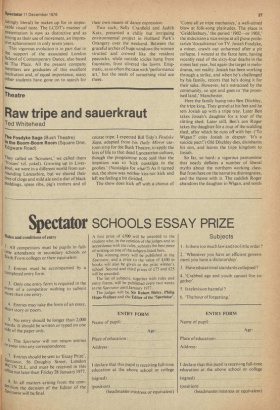

Floating chiffon dresses, solo piano music and Gallic visions predominated in a week which saw several London premieres mounted by a trio of contrasting dance companies. First on stage was the threatened New London Ballet, establishing a strong case for survival with an enjoyably varied programme at the Wimbledon Theatre. If the troupe is forced to disband in April through lack of subsidy, as sadly announced by its director Andre Prokovsky, then homes must surely be found for the best of its creations.

Examples of these were featured on opening night : a revival of Ronald Hynd's evocative shipboard romance to Ravel's Valses Nobles et Sentimentales: an exhilarating Faust Divertimento, typical of the bravura showpieces which have brought the New London so devoted a following; and a lovely new work by Prokovsky, Soli Blue Shadows.

His title is taken from one of five Verlaine poems, set for soprano by Faure after a Venetian sojourn in 1891. These combine with piano and cello duets by the same composer, dreamy blue designs by Peter Farmer and lyrical choreography to establish a quiet, rapt atmosphere. It's a ballet of passionate meetings, mysterious separations, which are focused by an extended duet for Prokovsky and his wife, Galina Samsova. Here their years of close collaboration produce a mutual empathy that is deeply moving. They enhance and reflect each other's every gesture, seeming to dissolve into partnership so that transitions become seamless, the most daunting lifts and balances effortless. A unique pair, the Prokovskys, and what criminal waste if they are forced by the dissolution of the New London to peddle their extraordinary talents round the international Gala circuit.

More drifting gowns for the women, chest-baring body tights for the men in the season's other premiere, Metamorphosis, by young Jonathon Thorpe of the Northern Dance Theatre. He chose the first three movements of Mendelssohn's Octet to accompany his abstract work, the fragmented sections being woven together by the darting figure of Michael Ho. A promising sketch and, like the majority of the other ballets, well danced. The only jarring note of the week was struck by guest star Maina Gielgud, whose camp solo by Bejart, Bhakti, and overpowering presence in Vespri, destroyed otherwise carefully balanced programmes. With ballerinas of the calibre of Samsova and Marian St Claire already part of this compact group, such an exotic visitor seemed redundant.

The next flurry of chiffon came with the Royal Ballet's performance of Adagio Hammerklavier by Hans van Manen, though the adjective 'flurry' could never be applied to the measured, reflective movement devised by this distinguished Dutch choreographer. Three couples are suspended in a timeless space where Jean-Paul Vroom's gauze back-curtain ripples in an eternal breeze, the women's soft skirts rise and fall as they are carried in long arcs by their partners. Originally inspired by Christoph Eschenbach's playing of the slow movement of Beethoven's revered piano sonata, here Anthony Twiner emulates the chosen model with great care and sensitivity. Sensitive, too, the manner in which van Manen has established emotional variations in the successive pas de deux, while remaining in harmony with the sombre score. The Royal cast, guest Natalia Makarova with David Wall, Jennifer Penney and Wayne Eagling, Monica Mason and Mark Silver, perform the flowing as well as the suspended phrases most elegantly, but if memory serves, the original Dutch National Ballet sextet had the edge on dramatic interpretation, clearly defining the different relationships among the duos.

Adagio Hammerklavier is a fine addition to the handful of van Manen works already possessed by the Royal, although its value would have been enhanced had it been commissioned. The extended Opera House ballet season includes only a single world premiere (John Neumeier's Mahler Symphony, scheduled for March), so it is as well for the development of British dance that we also support a company as creatively bountiful as the London Contemporary Dance Theatre.

This Graham-based ensemble includes five productions new to the capital in a three-week season at Sadler's Wells, ending 18 December. The size and enthusiasm of the audiences prove the quality of Robert Cohan's leadership. For not only has the Artistic Director built a magnificent team of performers, adapting Martha Graham's technique to the British physique and temperament (as demonstrated in his Class), but also encouraged a number of exciting choreographers from within the ranks while maintaining and diversifying his own choreographic output.

The diversity of Cohan's range was proved by the introductory showing of Nytnpheas. Imbued with the radiant shimmerings of Monet's waterlilies, accom panied, inevitably, by Debussy piano music, the movement is a departure from the style associated with the LCDT and Cohan himself. instead of using gravity to power movements, as is normally the case with contemporary dance, Cohan has sought to , achieve a feeling of weightlessness and fluency through near-balletic solos and

groupings. In a serene duet for Linda Gibbs and Robert North it was difficult to believe that Gibbs was not wearing pointe shoes, O) skimming and fleet her passage. These dancers have the advantage of early classical training; others in the cast found more difficulty with an alien idiom. The end result was that the most effective sequences were those in which dappled bodies formed a frieze along the slanting ledges of NobertO Chiesa's white wall. A truly impressionistic image of stillness was created, one that seemed to ripple in the mind's eye.

More familiar pleasures followed this experiment, with Siobhan Davies's Diary' (presented last year but with a new and less distracting score by Morris Pert) and Robert North's pop-hit celebration of machismo, Troy Game. The choreographers have given themselves important roles, with justification, for each has a rare ability: they cat concentrate on their own performance, t° superb effect, and simultaneously challenge colleagues to greater heights. But, of the two, Davies seems the more perceptive, original talent. Whereas North wittily emphasises in Troy Game the self-parody inherent in a muscleman like Namron, Davies explores the tenderness that hides beneath that woe monumental frame. Her duet for Namroo and the luscious Cathy Lewis in Diary. during which they move gradually along a horizontal band of rosy light, is emphatic' ally sensual yet gentle and kind. Similarly, in her delightful Pilot, the youngsters 'on the road' shake off their exhaustion in vit&. athletic dances, without ever losing their individuality. Davies's palette has subtle rather than primary colours, and highlights the less obvious facets of character. Each gesture acquires lucid meaning within a satisfying whole. The same cannot be said of the LCD1"s other emergent choreographer, Micha gese. In his latest, offering, Nema, the 'thread of a man's life' becomes confusing tangled. The idea of having three Mee represent the central character's Past' present and future, each interacting with 0 mother and a mistress/wife figure, soulitts promising. In practice, however, there Is insufficient variety of movement to delineate the different aspects (though the futu,re, seems most agitated), or to sustain tn't complex structure. Bergese, on this and Pas evidence, seems more of a dramatist, and a cerebral one at that, than a choreograPhe‘r per se. But he has a provocative approac", which may yet produce a convincing creee tion. The designs, by his sister Bettina, striking. Cohan is no mean designer himself, Pr the title Charter scattered through the, programme credits signifies that the ArtIstl; Director is responsible for lighting

costumes or both. More plaudits to tb,` chief, then, for what he sometimes lacks in musicality (his use of Schoenberg's Secoq, String Quartet for Place of Change is arl tatingly literal) he makes up for in impeccable visual taste. The LCDT's manner of Presentation is now as distinctive and as strong as their use of movement, an impressive achievement in only seven years.

This vigorous evolution is in part due to the support of the associated London School of Contemporary Dance, also based at The Place. All the present company members are graduates of this excellent institution and, of equal importance, many Other students have gone on to search for 110,

their own means of dance expression.

Two such, Sally Cranfield and Judith Katz, presented a chilly but intriguing environmental project in Holland Park's Orangery over the weekend. Between the graceful arches of huge windows the women strutted and crowed like the resident peacocks, while outside icicles hung from fountains, frost silvered the lawns. Enigmatic, as so often the case with 'performance art,' but the seeds of something vital are there.

Previous page

Previous page