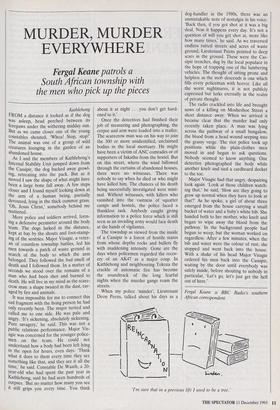

MURDER, MURDER EVERYWHERE

Fergal Keane patrols a

South African township with the men who pick up the pieces

Kathlehong FROM a distance it looked as if the dog was asleep, head perched between its forepaws under the withering midday sun. But as we came closer one of the young constables shouted, 'Whoa! Stop, stop!' The animal was one of a group of wild creatures lounging in the garden of an abandoned house.

As I and the members of Kathlehong's Internal Stability Unit jumped down from the Cassipir, the dog backed away growl- ing, retreating into the pack. But as it moved I saw the shape of what might have been a large bone fall away. A few steps closer and I found myself looking down at the arm of a human being, partially devoured, lying in the thick cummor grass. `Oh, Jesus Christ,' somebody behind me muttered.

More police and soldiers arrived, form- ing a defensive perimeter around the body team. The dogs lurked in the distance, kept at bay by the shouts and foot-stamp- ing of the sentries. Major Visagie, a veter- an of countless township battles, led his men towards a patch of waste ground in search of the body to which the arm belonged. They followed the bad smell of death and I followed them. In a matter of seconds we stood over the remains of a man who had been shot and burned to death. He will live in my mind as the scare- crow man: a shape twisted in the dust, rav- aged by fire and animals. It was impossible for me to connect this sad fragment with the living person he had only recently been. The major turned and called me to one side. He was pale and angry. 'It's sickening, absolutely sickening. Pure savagely,' he said. This was not a public relations performance. Major Vis- agie was concerned for the younger police- men on the team. He could not understand how a body had been left lying in the open for hours, even days. 'Think what it does to them every time they see something like that, and they see it all the time,' he said. Constable De Waath, a 20- year-old who had spent the past year in Kathlehong, said he had seen hundreds of corpses. 'But no matter how many you see it still grips you every time. You think

about it at night „ . you don't get hard- ened to it.'

Once the detectives had finished their job of measuring and photographing, the corpse and arm were loaded into a trailer. The scarecrow man was on his way to join the 300 or more unidentified, unclaimed bodies in the local mortuary. He might have been a victim of ANC comrades or of supporters of Inkatha from the hostel. But on this street, where the wind billowed through the curtains of abandoned houses, there were no witnesses. There was nobody to say when he died or who might have killed him. The chances of his death being successfully investigated were mini- mal. Without witnesses, with killers who vanished into the vastness of squatter camps and hostels, the police faced a thankless task. Anybody caught giving information to a police force which is still seen as an invading army would face death at the hands of vigilantes.

The township as viewed from the inside of a Cassipir is a forest of hostile stares from whose depths rocks and bullets fly with maddening intensity. Gone are the days when policemen regarded the recov- ery of an AK47 as a major coup. In Kathlehong and neighbouring Tokoza the crackle of automatic fire has become the soundtrack of the long fearful nights when the murder gangs roam the streets.

When my police 'minder', Lieutenant Deon Peens, talked about his days as a dog-handler in the 1980s, there was an unmistakable note of nostalgia in his voice. `Back then, if you got shot at it was a big deal. Now it happens every day. It's not a question of will you get shot at, more like how many times,' he said. As we traversed endless rutted streets and acres of waste ground, Lieutenant Peens pointed to deep scars in the ground. These were the Cas- sipir trenches, dug by the local populace in the hope of trapping one of the lumbering vehicles. The thought of sitting prone and helpless as the mob descends is one which fills every policeman with horror. Like all the worst nightmares, it is not publicly expressed but lurks eternally in the realm of private thought.

The radio crackled into life and brought news of a killing on Mosheshoe Street a short distance away. When we arrived it became clear that the murder had only recently taken place. A man was lying across the pathway of a small bungalow, the blood from a head wound seeping into the grassy verge. The riot police took up positions while the plain-clothes men moved in and began to ask questions. Nobody seemed to know anything. One detective photographed the body while another knelt and tied a cardboard docket to the toe.

Major Visagie had that angry, despairing look again. 'Look at those children watch- ing that,' he said, 'How are they going to grow up normal when they have to look at that?' As he spoke, a girl of about three emerged from the house carrying a small bucket of water and a baby's white bib. She handed both to her mother, who knelt and began to wipe away the blood from the pathway. In the background people had begun to weep, but the woman worked on regardless. After a few minutes, when the bib and water were the colour of rust, she stopped and went back into the house. With a shake of his head Major Visagie ordered his men back into the Cassipir, waiting by the door until everybody was safely inside, before shouting to nobody in particular, 'Let's go, let's just get the hell out of here.'

Fergal Keane is BBC Radio's southern African correspondent.

'I'm sure that in a previous life I used to be a tree.'

Previous page

Previous page