Architecture

The Palladian Revival: Lord Burlington, His Villa and Garden at Chiswick (Royal Academy, till 2 April) Lord Burlington's Town Architecture (RIBA Heinz Gallery, till 1 April)

Rigid professionalism

Alan Powers

He or she who buys balsamic vinegar or orders a café espresso is motivated not only by the taste of the thing. There is the desire to recreate in our northern climate a little of the presence of Italy, as if a part could act for the whole. Is this what Lord Burlington was doing in building his villa at Chiswick in the 1720s? More than the majority of Grand Tourists, Burlington, by the time of his second Italian journey in 1719, had clarified his focus on architec- ture. Returning laden with architectural drawings by Palladio, his head full of pre- cise observations on Palladio's buildings, he was able to become an architect of some ability having hitherto been only a patron.

The Italian painter Scipio Maffei called Burlington `ii Palladio e it Jones dei nostri tempi'. Inigo Jones had gone through the same act 100 years before, and brought back his set of Palladio drawings and his annotated edition of I Quattro Libri delPArchitettura, as one might today bring back a car boot load of majolica and mar- bled paper notebooks. This was no mere consumerism, however, for each contribu- tor to the whole had aspired to recapture more authentically the spirit of Roman antiquity from the scattered evidence. When this accumulated set of drawings from Palladio, Jones and John Webb was also bought by Burlington, he had a formidable corpus over which to range his cool and discerning eye.

The concurrent exhibitions at the Royal Academy and the RIBA Heinz Gallery show what Burlington was able to achieve with his hoard. Lesson one in Georgian architecture is that Burlington deliberately supplanted the baroque of Christopher Wren and the Office of Works and acted as a style policeman to a whole generation. This view has been rightly modified to allow Hawksmoor a place as a precursor of Roman magnificence. The contrast in the Heinz Gallery exhibition between the early muddled designs for the dormitory at Westminster School by William Dickinson, delegated by Wren for the job, and Burlington's sublime simplicity which car- ried the commission, show that the reform was not merely factional or ideological, although one may regret the early passing of English baroque.

For the Royal Academy exhibition, the curator John Harris has clearly assembled the complex documentation of Chiswick so that Burlington's performance there retains its distinctive flavour. For all of its being a precursor of English Palladianism, no other building like this was ever built, so precise in every stone joint and in every derivation of its parts, but assembled into an entity that is only just contained within its rigid bounding lines of rustication, string course and cornice. It is clear that Chiswick has little connection with Palladio's Villa Rotunda, although wooden models of each stand in the RA to suggest the contrary. Burlington was playing a game of citation that Palladio himself had begun, in which the architectural forms are taken as invari- ables, and the art is to compose them.

John Harris is surely right to emphasise the originality of the Chiswick interiors, once rather carelessly attributed to Burlington's protégé William Kent, who contributed to the decorative ceiling paint- ing. The exquisite carving introduces a fris- son of antiquity stronger than anything found in Palladio's more relaxed applica- tion of stucco and decorative painting in the Veneto. This is the case above all in the upper room of the 'Link Building', added later by Burlington to join his toy-like villa to the existing Jacobean house next door. Here is an interior with screens of Corinthian columns that has all the restrained richness of the Adam Brothers' recreation of antiquity in the 1760s. Horace Walpole considered the courtyard outside this building 'more worth seeing than many fragments of ancient grandeur which our travellers visit under all the dangers atten- dant on long voyages'. Thus, presumably, the desired effect of Italy in England had been achieved.

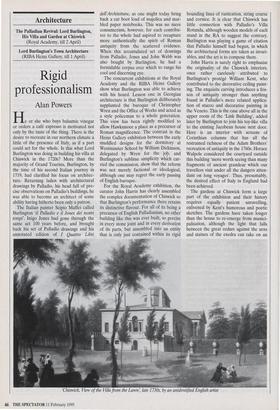

The gardens at Chiswick form a large part of the exhibition and their history requires equally patient unravelling, enlivened by Kent's humorous and poetic sketches. The gardens have taken longer than the house to re-emerge from munici- palisation, although the light that falls between the great cedars against the urns and statues of the exedra can take on an `Chiswick, View of the Villa from the Lawn; late 1730s, by an unidentified English artist Italian glow, as seen in the marvellous set of paintings by George Lambert and others on loan from Chatsworth.

What is remarkable is the resistance of house and garden to any emblematic or symbolic interpretation, although some have tried. Perhaps the diet of taste and civic virtue becomes a little wearing, yet the basis of Burlington's programme was that architecture is not amusement. Who but a man of Burlington's high principle could design Assembly Rooms in York where the correct intercolumniation of the Corinthian order meant that ladies in hooped petti- coats could not squeeze between them? In this he most clearly passes from the rank of amateur to professional architect.

Previous page

Previous page