Profile

A man for all Ireland?

Olivia O'Leary

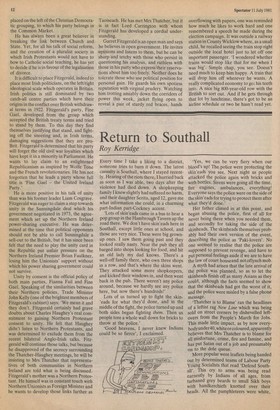

It was the best political show in Dublin for years. A fortnight after a tied election Dail Eireann, the Irish Parliament, was meeting to pick the winner. In the packed chamber the outgoing premier, Charles Haughey, played his favourite role of dignified statesman, oozing composure and regal pride as they voted him out of office. Across the floor a big, fussy man with spectacles made frantic notes, whispered busily to his colleagues, jumped around in his seat — for all the world like the secretary of a student debating society. Garret Fitzgerald has no time for gravitas.

He is, on the other hand, an intensely serious politician. He assumes that people are interested in the content of what he says and the efficacy of what he does. Rather than sell himself, he prefers to sell ideas, and he is particularly proud of his own. His only major concession to his personal image-builders was to go to a professional hairdresser rather than have his wife cut his hair at home. He is constantly embarrassed at the antics demanded of popular politicians. He is good on ideas, but not good on parliamentary tactics. With the shaky minority coalition government he leads, sustained by unpredictable independents, that lack of parliamentary skill is a major handicap. His government has already been defeated twice this week on significant votes in the Dail. Dirty tricks are part of survival in parliament, and Fitzgerald is too gently bred to fight dirty.

Fitzgerald is at once upper-class and of impeccable nationalist pedigree. Like most Irish Fitzgeralds, he claims descent from one of the old ruling Norman families, but his nationalist credentials are even more valuable. His father, Desmond, a professor of philosophy, was director of publicity for the rebel Irish government in the war of independence and was later Minister for Foreign Affairs. Both his mother and father were among the insurgents fighting from Dublin's General Post Office in the 1916 Rebellion — many a roaring Irish Republican would love to claim the same. Fitzgerald does not flaunt his family history as often as his more nationalist supporters would like. His intellectual vanity would probably not allow him to score such an easy point, and in all fairness to the man, he prefers to persuade than to impress.

While his father was an austere man, eventually disillusioned by politics, Garret Fitzgerald is approachable, optimistic, and a compulsive talker. This last is a family trait. A friend remembers seeing Garret and his brother at a party, sitting back to back in a Victorian conversation seat, both talking at the same time, each to the other, without pause and for hours on end. For the shy and the reticent, dinner parties with the young Fitzgeralds were bewildering, with the talk ranging exuberantly from politics to literature to philosophy, and the Fitzgeralds talking one another into incoherence, faster than the human ear could follow.

Fitzgerald senior was a committed Francophile, as is Garret Fitzgerald. Garret's wife Joan, who grew up speaking French in Geneva, first met him at a French Society meeting at University College, Dublin, where she remembers she didn't much like him and he spoke rapid French with a deplorable accent.

Despite degrees in law and history, Fitzgerald eventually discovered his greatest obsession: economics. He worked with Aer Lingus, the national airline, and then set up his own economic intelligence agency. He was Dublin correspondent for the Financial Times and then became a lecturer in political economy at UCD.

Garret loves figures. Get him on to a statistical subject and it's like hitting the jackpot on a fruit machine. Figures pour out, and he adds in percentages to clarify the situation. He has been told not to do it; he has been begged not to do it because the public don't like it. Cartoonists have a field day.

His memory for vast amounts of detail was a legend at Aer Lingus, where he dazzled his first interview board by reciting to them flight number by flight number the PanAm schedule down the coast of Amer ica. He is not so good at remembering other things — like the suit which he left at the cleaners somewhere in Dublin but couldn't remember where: or the coat he can't find: or that he parked but can't remember where. He thrives on young people; their eagerness and their innocence somehow match his own. He does not understand cynics, which may present a crisis of understanding with a large percentage of the Irish population. In fact, he finds cynics very boring. They may feel the same way about him.

fie bundled young people off on picnics with his family when he was a lecturer at UCD. He bundled them into the party in thousands when he became leader. He has now bundled them into one of the youngest Irish cabinets ever. Neither the Finance, Agriculture nor Education ministers are yet 40. Fitzgerald is 55, and looks more.

Rather than choose a political party, Garret Fitzgerald set out to change Fine Gael, his father's party, to his liking. He fought to introduce a social justice policy into what used to be a very conservative party, and in the process he himself replaced its conservative leader. He modernised its approach, and revitalised its organisation. But Garret isn't a radical, he is an enlightened liberal. He believes in improving the way things are run, rather than committing himself to fundamental change. He will work for efficient, professional government, which would be benevolent towards the deprived and generous in extending opportunity. He does not object to being called a Social Democrat, but the label isn't accurate. Fitzgerald is better placed on the left of the Christian Democratic grouping, to which his party belongs in the Common Market.

He has always been a great believer in breaking the link between Church and State. Yet, for all his talk of social reform, and the creation of a pluralist society in which Irish Protestants would not have to bow to Catholic social teaching, he has yet to decide if he is in favour of the legalisation of divorce.

It is difficult to place Fitzgerald, indeed to place most Irish politicians, on the left/right ideological scale which operates in Britain. Irish politics is still dominated by two catch-all centre parties which have their origins in the conflict over British withdrawal terms in 1922. Fitzgerald's party, Fine Gael, developed from the group which accepted the British treaty terms and tried to stand by them. To this day they find themselves justifying that stand, and fighting off the sneering and, in Irish terms, damaging suggestions that they are proBrit. Fitzgerald is determined that his party will forget the old civil war loyalties which have kept it in a minority in Parliament. He wants to lay claim to an enlightened Republicanism as inspired by Wolfe Tone and the French revolutionaries. He has not forgotten that he leads a party whose full title is 'Fine Gael — the United Ireland Party.'

He is more positive in his talk of unity than was his former leader Liam Cosgrave. Fitzgerald was eager to claim a step towards unity in the Sunningdale deal which his government negotiated in 1973, the agreement which set up the Northern Ireland power-sharing executive. He was determined at the time that political opponents should not be able to call Sunningdale a sell-out to the British, but it has since been felt that the need to play the unity card in the Republic put unfair pressure on the Northern Ireland Premier Brian Faulkner, losing him the Unionists' support without which his power sharing government could not survive.

Unity by consent is the official policy of both main parties, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael. Speaking of the similarities between their Northern policies, Trade Minister John Kelly (one of the brightest members of Fitzgerald's cabinet) says: 'We mean it and they don't. Fitzgerald certainly had grave doubts about Charles Haughey's real commitment to gaining Northern Protestant consent to unity. He felt that Haughey didn't listen to Northern Protestants, and was determined to exclude them from the recent bilateral Anglo-Irish talks. Fitzgerald will continue those talks, but because he disapproved of the secrecy surrounding the Thatcher-Haughey meetings, he will be insisting to Mrs Thatcher that representatives of both communities in Northern Ireland are told what is being discussed. Fitzgerald's mother was a Northern Protestant. He himself was in constant touch with Northern Unionists as Foreign Minister and he wants to develop those links further as Taoiseach. He has met Mrs Thatcher, but it is in fact Lord Carrington with whom Fitzgerald has developed a cordial understanding.

Garret Fitzgerald is an open man and says he believes in open government. He invites opinions and listens to them, but he can be sharp and tetchy with those who persist in questioning his analysis, and ruthless with those in his party who express their reservations about him too freely. Neither does he tolerate those who use political position for personal gain. He guards his own spotless reputation with virginal prudery. Watching him trotting amiably down the corridors of power this week, jacket flying open to reveal a pair of sturdy red braces, hands overflowing with papers, one was reminded how much he likes to work hard and one remembered a speech he made during the election campaign. It was outside a railway station in County Wicklow where, as a small child, he recalled seeing the train stop right outside the local hotel just to let off one important passenger. 'I wondered whether trains would stop like that for me when I was big'. Simple chap, you see. Doesn't need much to keep him happy. A train that will drop him off wherever he wants. A really complicated economy to gel his teeth into. A nice big 800-year-old row with the British to sort out. And if he gets through that lot by lunchtime, there's got to be an airline schedule or two he hasn't read yet.

Previous page

Previous page