The spy who lost me

Murray Sayle

Tokyo Comparatively few of the journalists 1 i know are spies, but the reverse, alas, is far from true. In mediaeval times, assassins took jobs as court barbers, giving them a perfect right to hold a razor to the king's throat. So, in our own day, people who want to go around asking questions, taking Photographs, and getting drunk with politi- cians and military men find a press card the ideal camouflage. Some of the less readable publications, it appears, are staffed almost entirely by spooks, if we can accept the word of Stanislav A. Nall me Stan') Lev- chenko of Moscow, Tokyo and now Washington DC. I first ran into Stan at one of those monumentally dull conferences on peace, or it might have been border conflicts in the Far East, run by Quakers and in conse- quence dry as the Gobi Desert. He looked to be in his thirties, with a bow tie, sunglasses and a tartan jacket — the get-up of a man trying not to look suspiciously in- conspicuous. He worked, he said, for New Times, which I dimly remembered as a rock-and-roll magazine from New York. No, not that New Times,' said Stan. 'Is good joke. New Times is publication of the Soviet Trade Union Federation. In Moscow.'

BY a million-to-one chance, Stan had a Copy with him, which he invited me to look Oyer. It was in English, of a ponderous kind, and carried reports from every corner of the world — everywhere, in fact, where h umanity groans under the iron hoof of US imperialism and its lackeys, including the capitalist ruling circles of Japan. Very interesting', I said, diplomatically. You think so?' said Stan. 'We must talk more. Come round to my house some time. I have plenty of literature there. And vodka.' Somehow, the thought of leafing through bound volumes of the New Times, picking out Stan's contributions from the surrounding stonework, was less than ap- pealing. Would I suddenly find myself on camera, with a busty stewardess from Aeroflot? I later heard that Stan was respectably, even tediously married, and family evenings with boiled turnips and beer were more his speed. Somehow, I never found myself at a loose enough end to take him up on his invitation. I saw, however, quite a bit of Stan over the next few years. He seemed keen to get t and about, and together we splashed through shipyards, paced the sooty halls of steel mills, and soaked up the secrets of Japanese piano production. I soon found that he was not well up on Bernstein revi- sionism or Lenin's Imperialism, the Last Stage of Capitalism. He did show, however,

an obsessive interest in figures, on such sub- jects as Japanese output of pig-iron per man per shift, and he took copious notes in, as far as I could read over his shoulder, English (another Soviet journalist accused of buying information from a sailor off the

USS Midway was stated by the Tokyo police to have kept a notebook in Russian).

And it was clear, from an article he showed me on Japanese bamboo basket weaving, that Stan was no graceful prose stylist either.

Still, the Tokyo press corps was startled to hear, in October 1979, that Stan had defected to the US. Equally unexpected was the manner of his going. It seems that KGB men are followed around by other KGB men, although logically this process must have a limit somewhere, before it engulfs the whole human race. Stan, for one, took no chances, and instead of just checking in at the US embassy, spent a whole afternoon touring Tokyo, ducking in and out of taxis, using different subway exits and the front and back doors of hotels, before finally ar- riving breathless at the Sanno Hotel, in cen- tral Tokyo, and asking to see 'a senior in- telligence officer', The Sanno, a peeling relic of the US occupation of Japan, ac- commodates service people on leave, and Stan had all unknowingly gatecrashed a US navy party.

Soon, however, a `tall, grey-haired man named Robert' appeared, and after a Sleepless night at a safe house — there may, after all, be Kim Philby types in the CIA Robert obliged with a US visa and a first- class air ticket, one way, to Washington. According to Stan's later account, he just made it through Tokyo airport ahead of a posse of vengeful Russians, although these may, of course, have been, like the spots on

Lady Macbeth's hands, the phantoms of a fevered brain.

Stan's movements over the next three years are, like much less in his story, mysterious. He may have been resident in that village deep in the woods of Washington State where everyone is said to have a recent nose job and tinted contact lenses. He may, on the other hand, have had business closer to the other Washington where, in July last year, we find him testify- ing before a closed session of the In- telligence Committee of the US House of Representatives, an appearance Stan described in his opening remarks as 'a great honour'.

Born, it seems, with a stainless steel spoon in his mouth, the infant Stan wanted for nothing the socialist system could

supply. His father was a major-general in chemical warfare research, his stepmother a pediatric surgeon, his own mother having died when he was three. (A hint, there, of a love-starved childhood?) Stan was educated at a special high school for the offspring of party big shots in Moscow, and studied Japanese for six years at Moscow Universi- ty, writing his master's thesis on the Japanese peace movement.

Then, as a reserve Red Army officer, Stan qualified as an intelligence operative (illegal), his assignment on the approach of war being to proceed to Britain and gather intelligence on the state of readiness of British nuclear strike forces. The selection of a Japanese expert for a job in England, or possibly Scotland, suggests that the Red Army works on lines comfortingly close to our own.

In 1971, Stan was invited to join the KGB. He trained on the job for the next three years, followed by a year in the editorial offices of New Times in Moscow `to improve', as he said, 'my journalistic skills'. As he explained to the committee, `To be able to dissolve into the interna- tional journalistic community in Tokyo... I had to have real journalistic experience.' According to Stan, New Times (the Soviet version) was started in 1943 solely to give Soviet spies cover jobs, and ten of its twelve foreign correspondents when he was there were KGB men. Early in 1975, Stan arrived to begin his dual assignment in Tokyo.

By his own account, Stan's field career with KGB got off to a spying start. Once or twice a month he filed a piece for the New Times, meanwhile having 20 to 25 clandestine meetings a month with 'agents of the KGB's network in Japan', who number, he said, 200 in all. By 1979, Stan said, he was handling 'ten agents and developmental contacts,' including four 'agents' he had personally recruited in the previous four years. As a result of this good work, Stan said, he was promoted to major by the grateful KGB a few weeks before he defected.

Asked for a practical sample of his work, Stan told the congressman that he had, on orders from Moscow, used his contacts with Japanese journalists to get then- President Jimmy Carter labelled 'Neutron Carter' in the Tokyo press. He did not, un- fortunately, elaborate on his method, which we can only surmise was a series of telephone calls: 'Hello, Hitoshi? Heard the latest? They're calling Jimmy Carter "Neutron Carter". Get it? Is funny joke, yes? Ha, ha.' The name, despite Stan's efforts, did not catch on.

Stan's Washington testimony in fact created little stir in Japan when it was released late last year. Spying is not, as such, against the law in Japan, as in princi- ple the country has no offensive armed forces or hostile designs on anyone, and so there is nothing to spy on. With 150,000 bars in Tokyo alone, many up mysterious back alleys, working conditions are ideal, and Stan himself has described Japan as 'a paradise for spies'. Obviously the KGB, like MI6 and every other self-respecting spy out- fit in the world, bases its Far Eastern opera- tion in Tokyo, and Stan's work, as he described it to the committee, sounded about as harmless as could be, while still allowing Stan to draw his KGB salary and expenses with a clear conscience.

Stan's next set of disclosures, made to of all publications — the Reader's Digest, have made more headlines. His motives are again unclear. He may, of course, have been drawn to the Digest as a simple reader, Enriching His Word Power, or applying Laughter, The Best Medicine. Then again, he may have been attracted by the Digest's

reputation, greatly exaggerated, of being the best payer in the business. Was Stan the spy who came in for the gold? Or it may be

that, working with writer John Barron, himself a former US Navy intelligence. of- ficer, Stan was simply pouring his apologia pro vita sua into the porches of a sym- pathetic ear.

In any event, his current set of amazing revelations contains, for the first time,

some names. Most are in-house pseudonyms like 'Ulanov', `Kamus', `Grace', 'Kanto' and 'Thomas'. These shadowy people, says Stan in the May edi- tion of the Japanese version of the Digest, are among the 200 politicians and jour- nalists who were 'agents' or 'collaborators' when he was working with the KGB in Tokyo.

As he tells it, most of Stan's really spec- tacular spying efforts were with these phan- toms. He cites, for instance, his 'brush con- tacts' with a Japanese journalist, code- named 'Ares', who used to slip Stan microfilms as they walked past each other, by pre-arrangement, in a Tokyo street. Stan would then place the films in a box bolted to a waiting KGB car, the box wired to burst into flames if tampered with, and Stan would take a second stroll to pass `Ares' with an envelope stuffed with yen. This scene is surely from a James Bond film or, if not, should surely be in the next. `Ares', said Stan, was getting the stuff from `Schweik', described as 'a man in his forties working for Japanese intelligence'. (Again, Japan is not officially supposed to be in the intelligencelbusiness, but therelisian outfit called the 'Cabinet Research Room' which is said to gather the odd fact now and again.) Stan claimed to have run a personal stable of 26 'agents' of this kind, although these included, he said, 'friendly people who mix with KGB officers disguised as journalists, and people likely to become Soviet friends after approaching them'. And, as he told the Washington committee, `I have knowledge of some approaches to some British journalists'. Some of these people, Stan conceded, might not be aware that they appeared on the KGB's books as `agents' or 'collaborators'. His method, he said, was to 'enmesh them in a web of gifts', starting, apparently, with a free copy of the New Times.

To make his story more credible, he says, Stan names eight real people in his current set of disclosures with the promise, or threat, of more 'depending on the situation in the future'. The biggest fish from the Japanese political pond is Hirohide Ishida, a former labour minister and still a back- bench member of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party. Ishida has also been for many years president of the 500-member Parliamentary Group for Japan-Soviet Friendship which must be, if Stan's story is true, surely the most transparent cover in the history of espionage. Stan says he pass- ed on to Ishida orders from Moscow that

Ishida should persuade the Japanese cabinet to return a MIG-25 fighter whose pilot defected to Japan in 1976. The plane in fact went to the US, but the grateful Ros" sians, according to Stan, released 20 Japanese fishermen they had locked up for catching squid in Soviet waters (Ishida comes from a seaside electorate).

Ishida denies being Stan's agent, or

accepting money, but says he may have once met someone answering Levchenko's description at a party at the Soviet embassy. Next on Stan's list is Takuji Yamane, managing editor of the Sankei Shimbun, a conservative businessman's newspaper. Stan disclosed that 'Chou En-lai's will , forged by the Russians to indicate dissen- sion in the Chinese leadership, was passed to Yamane for publication in the Sankei not, interestingly enough, by Stan himself, but by his KGB predecessor.

Respectable Japanese newspapers follow

a curious oriental code of ethics which re- quires an editor who publishes a forged document to resign. Yamane has done so, protesting that he had done nothing against `Japan, the fatherland I love', and adding; `All I can say is, it is Levchenko's word against mine'. Similar denials have come from the other 'agents' named by Stan, who include a former chairman of the Japan Socialist Party, the secretaries- general of a socialist study league and an overseas cultural association, a Japanese, freelance journalist and an executive 0' Television Asahi. Asked why 18 more of his `agents' were not named, Stan explained that in cases of this sort Japanese often commit suicide. None have in fact yet done so. The Japanese foreign ministry has also reported finding no trace of 'Nazar', the treasonable Japanese diplomat who, accoro ding to Stan, passed him the contents f caobrdIles. from Japanese embassies around the world. As a result of his new disclosures, we have, however, more information about Stan the man, and the intriguing problem of his motivation. He found God,says' he

quite early in his career, and became

r secret churchgoer while still in Moscow.s, saw no signs of this myself, I must confes but, as Stan says, `If my former colleague s bhy thadke Soviet th nownviaboauutito,rIitwie,. would be persecuted ing my frustrations in long hours o was alsov,et impress' it re the that Stan was happy in his wMoryk seems, mistaken: 'My career in the So ie Union was successful not because I believed it it was proper to do what I had been 'I Was he told the Washington committee. Back in Moscow on leave bebfoot

working as a high performance ro , ,

of wOrk• disgust that coSntasntruscatyjos,n hweorokbosen.rt.vtiehaiee uPinvv"the Olympic village was being held KGB men installed microphones d athletes' dormitories. 'I witnesses hand the fact that the Soviet d h 01 t ..ti its

it s' citizens,' he recalled. tocam

for the good

understanding that it is ate, corrupt c dictator-style regime with rotten moral standards.'

The crunch, however, apparently came in an area not unknown in the West, office Politics. If one man is, according to Stan, a living symbol of the rottenness of the whole Soviet system, it is Lieut-Colonel Vladimir Pronnikov, Stan's former boss in Tokyo. Pronnikov was, according to Stan, friendly on the surface (we all know that treacherous smile at the tea urn!) and even recommended Stan's promotion to captain. However, Pronnikov heard 'through an in- former' (they have this kind of rat in the KGB, too, apparently) that Stan disapprov- ed of Pronnikov's methods of undermining his boss. Pronnikov therefore set out to block Stan's promotion and even suggested

that Stan himself should spy on his KGBcolleagues. 'He felt', writes Stan's biographer, 'his old loyalty to Russia and his countrymen, to the honest KGB officers who like himself were cogs in an inhuman machine.' So, due in October 1979 to return to Moscow for a routine reassignment, Stan

chose Washington and the Reader's Digest instead.

thReading his self-portrait, it seems unlike ly that a man of Stan's talent, diligence and moral uprightness can have chosen freedom Only to join America's ten million unemployed. His curriculum vitae is the sort of thing, in fact, commonly attached to a job application, and it is understandable at he would show his Tokyo achievements in the most positive light. This raises perhaps the most interesting question of all:

has Stan, at 41, retired and if not, who is he working for now?

Unable to afford microfilms or brush contacts, we can do no more than survey the possibilities, which seem to be: (1) Jesus. Stan is operating under direct Divine supervision. Only his case officer in the sky can, with certainty, judge the depth

of his religious convictions. But here below, perhaps,

(2) Stan is working for the Cabinet Research Room. Unlikely. Japanese don't care much for Russians and in general prefer to employ Japanese if at all possible. Besides they don't pay nearly as well as (3) The CIA, where Stan may be angling for a job. 'It is an honour for me to meet such highly professional, highly motivated and determined officers whom I have met from the Central Intelligence Agency', he told the committee in Washington. You can't

get fairer than that. Or maybe

(4) Stan already has a job with the CIA. His byline has certainly dropped from sight lately, and he must be doing something for a crust. It is, however, inconceivable that the Company would authorise Stan to pick up Pin-money, even in instalments with his memoirs Now, what interest would the

C A ics have in the intricacies of Japanese polit?

As things stand, quite a bit. In Yasuhiro Nakasone, Japan now has the world's most enthusiastically pro-Reagan male prime minister: Nakasone is, however, having trouble in moving Japanese public opinion in the direction he would like, which isf to increase the defence budget, including heavy purchases of American weapons. This, certainly, is the direction Washington also prefers, as it would simultaneously reduce Japan's huge trade surplus with the US and engage Japanese taxpayers more deeply in the common defence effort.

The trouble is that, according to the polls, the Japanese public don't recognise the Russian threat. They prefer to see Japan as a bystander in the superpower struggle, enjoying an American defence guarantee, it is true, but otherwise free to do business with all sides. This is the line of the Japanese Socialist Party. It is possibly significant that Stan did not, by his own ac- count, have any dealings with the Japan Communist Party, which claims a voting strength of upwards of two million. But the JCP lives in a political ghetto, and has no influence on national policy. The Socialist Party is, on the other hand, the loyal op- position, with something like a veto (by procedural delays) on major measures. And of the eight people named by Stan, four

were socialists.

On the other hand, the Japanese Socialist Party is split into many hostile factions, some of them belonging to the kindergarten Left, and Stan may quite genuinely have found more people there ready to pass the time of day with him, and even wade through a copy or two of New Times.- It hardly took more, it seems, to figure in Stan's reports (and, no doubt, his expense sheets) as an 'agent'.

But Stan will have to produce bigger names, and more convincing evidence, if he hopes to move Japanese public opinion. `Levchenko's a flop', reported the Mainichi Shimbun, the paper which first splashed his amazing revelations. And, despite his net- work of informants, Stan does not seem to have any deeper insights into Japanese af- fairs than more conventional journalists have managed.

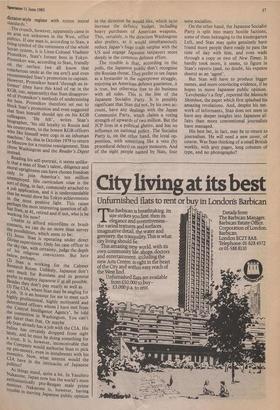

His best bet, in fact, may be to return to journalism. He will need a new cover, of course. Was Stan thinking of a small British weekly, with grey pages, long columns of type, and no photographs?

Previous page

Previous page