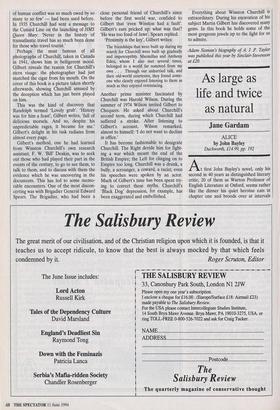

As large as life and twice as natural

Jane Gardam

ALICE A, first John Bayley's novel, only his second in 40 years as distinguished literary critic, 20 of them as Warton Professor of English Literature at Oxford, seems rather like the dinner his quiet heroine eats in chapter one and broods over at intervals throughout the book. It is cervelli fritti fried brains — in black butter, which she eats in a dark and comforting restaurant in Sorrento. Her host has 'a slight air of grub- biness' that is 'rather distinguished'. She finds the cervelli frith 'light and tasty', but there is something slightly disturbing about them. At one point she calls them offal. In fact with a different dust-jacket from this one which is lovely, like Rex Whistler (and unaccredited), and in the appropriate part of the bookstall, Alice could do very well as a light and tasty thriller with some hints of real evil going on just out of sight.

It has to do with innocents abroad. One is Ginny, 33, a virgin holidaying alone in Italy; the other, Tom, a post-graduate student spending time in miserable wintry Venice. Both are seduced by a brash and fascinating Australian girl, Alice, who uses them as innocent couriers of heroin. Back in London they meet trouble — a beating up for Tom, a near-rape for Ginny. Then Alice disappears — and so on. The settings for these adventures are as powerful and strange as a Fellini film. Vesuvius sleeps across the bay. A huge liner glides in with 'seemingly implacable intent'. Festering, oily Venice is hideously beautiful and the coast of East Kent with its lonely pale golf courses and isolated sea- side houses, 'classy, 1930s style as if pickled in its period by the salt air' is perfect. 'The distance, the otherness of this magical place', says John Bayley, is what draws Ginny to it and not its 'normal vulnerabili- ty'.

It is phrases like 'normal vulnerability' applied to landscape that make you realise quickly that Alice is more than a crime story written by an academic for fun although there is fun in it and a certain sly- ness. How serious, for example, are these fried brains? How far is it a joke when he talks about someone who is writing on 'a novelist with a name like breakfast food' (Musil) who 'with astonishing intellectual subtlety' writes about characters `without qualities, with no fixed personality' and 'who might do anything at any time'.

For the characters in Alice, like some in another book of that name, are not so far away from this. They tend to be erratic, either to drift or rush madly about. 'It is a question now of this, now of that' (Musil? The White Queen?). And even the crimi- nals tend to change their minds half way through a punch-up. Ginny's would-be rapist packs it in at the last moment ('Now he seemed to have lost his touch') and even dazzling, confident Alice, who expertly takes the heroine off to bed and organises silly Ginny's smuggling activities, has a habit of turning her face to the wall and wailing, 'Oh I am so miserable.' Poor Tom is about as street-wise as Peter Rabbit.

And just so, says John Bayley. People are like this. You don't want to believe all they tell you in the media. What most people are after is normality. Ginny, a publisher's reader, finds that modern novels give her the horrors, not because of their nastiness, but through the lack of attention to or understanding of what constitutes normali- ty:

She was frequently staggered after wading through something she had read to find herself back in the nice staid world she knew and which the author seemed determined did not exist.

But she is interested in normality, not con- vention. She is prepared to believe that her feelings for Alice are 'normal'. 'Sex', she says, 'is not necessarily something you have in an assignable form' and sex such as she has had to date — i.e. nil, which is more usual than is supposed — has up to now `not taken her very far'.

There is one really nasty piece of work in Alice, a Major Grey, who keeps turning up, laconic and sinister, in unexpected places. He is a liar, thief, con-man, drugs-dealer, woman-ditcher and double-crosser of every kind. Ginny comes upon him unawares on a golf-course, quietly putting, and the peace in his face moves her to desire. She wants to live with him for ever in a seaside house, taking walks with him on the links and going home each night for supper. Is he really so abnormal? Is there not some- thing beautifully normal somewhere in everyone? Maybe beautifully abnormal, writes about the sort of John Bayley people who usually evade the attentions of the novelist because 'they prefer not to be noticed', and it can't have been an easy book to write, especially in his restful, unemphatic style. The whole thing might have come out dismally tame, or dated. This does not happen. Alice is full of a life of its own. The rackety elements are very well done. As to being dated, it is not an old man's book. refuse to believe', Bayley says, quoting Larkin in the epigraph, 'that there is a thing called life that one can be in or out of touch with.'

`. . . and I'm sure that Albert will be looking up at . . I mean, looking down on us today . . . '

Previous page

Previous page