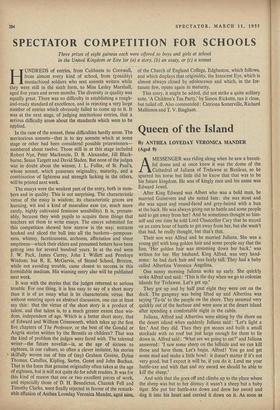

SPECTATOR COMPETITION FOR SCHOOLS

Three prizes of eight guineas each were offered to boys and girls at school in the United Kingdom or Eire for (a) a story, (b) an essay, or (c) a sonnet HUNDREDS of entries, from Caithness to Cornwall, from almost every kind of school, from (possibly) mustachioed soldiers who sent sonnets written while they were still in the sixth form, to Miss Lesley Marshall, aged five years and seven months. The diversity in quality was equally great. There was no difficulty in establishing a rough- and-ready standard of excellence, and in rejecting a very large number of entries which obviously failed to come up to it. It was at the next stage, of judging meritorious entries, that a serious difficulty arose about the standards which were to be applied.

In the case of the sonnet, these difficulties hardly arose. The meritorious sonnets—that is to say sonnets which at some stage or other had been considered possible prizewinners— numbered about twelve. Those still in at this stage included Robert Nye, Peter Mackenzie, D. B. Alexander, Jill Black- burne, Susan Targett and David Sladen. But none of the judges was in doubt about the winner, J. L. Fuller, of St. Paul's, whose sonnet, which possesses originality, maturity, and a combination of lightness and strength lacking in the others, will be printed next week.

The essays were the weakest part of the entry, both in num- bers and in quality. This is not surprising. The characteristic virtue of the essay is wisdom; its characteristic graces are learning, wit and a kind of masculine ease (or, much more rarely, highly cultivated feminine sensibility). It is, presum- ably, because they wish pupils to acquire these things that teachers set them to write essays. The essays submitted for this competition showed how narrow is the way; entrants hooked and sliced the ball into all the bunkers—pompous- ness, whimsy, facetiousness, archness, affectation and sheer emptiness—which their elders and presumed betters have been getting into for several hundred years. In at the end were J. W. Pack, James Currey, John I. Willett and Penelope Wisdom; but R. E. McGarvie, of Strand School, Brixton, while not avoiding trouble, came closest to success, in this formidable medium. His winning entry also will be published next week.

It was with the stories that the judges returned to serious trouble. For one thing, it is less easy to say of a short story than it is of an essay what is its characteristic virtue. But without entering upon an abstract discussion, one can at least say this: that the virtue of the short story is a product of talent, and that talent is, to a much greater extent than wis- dom, independent of age. Which is a better short story, that of Edward and William Crimsworth, which takes up the first five chapters of The Professor, or the best of the Gondal or Angria stories written by the Brontës as children? That was the kind of problem the judges were faced with. The talented writer—the future novelist—is, at the age of sixteen to eighteen, in our culture, so often a clever imitator, his stories skilfully woven out of bits of (say) Graham Greene, Dylan Thomas, Catullus, Kipling, Sartre, Genet and John Buchan. That is the form that genuine originality often takes at the age of eighteen, but it will not quite do for adult readers. It was for this kind of reason that one or two excellent pieces of work, and especially those of D. H. Benedictus, Chantek Fell and Timothy Clarke, were finally rejected in favour of the remark- able effusion of Anthea Loveday Veronica Mander, aged nine, of the Church of England College, Edgbaston, which follows, and which displays that originality, the Innocent Eye, whith is almost always closed by adolescence and which, in the for- tunate few, opens again in maturity.

This entry, it might be added, did not strike a quite solitary note. 'A Children's Tea Party,' by Simon Ricketts, ran it close, but tailed off. Also commended: Catriona Somerville, Richard Mallinson and T. V. Bingham.

Previous page

Previous page