'WE CANNOT AFFORD TO LOSE LIVES'

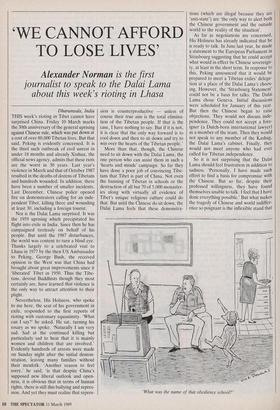

Alexander Norman is the first journalist to speak to the Dalai Lama about this week's rioting in Lhasa

Dharamsala, India THIS week's rioting in Tibet cannot have surprised China. Friday 10 March marks the 30th anniversary of the general uprising against Chinese rule, which was put down at a cost of over 80,000 Tibetan lives. But that said, Peking is evidently concerned. It is the third such outbreak of civil unrest in under 18 months and already Xinhua, the official news agency, admits that these riots are the worst in 30 years. Last year's violence in March and that of October 1987 resulted in the deaths of dozens of Tibetans and hundreds wounded. In addition, there have been a number of smaller incidents. Last December, Chinese police opened fire on demonstrators calling for an inde- pendent Tibet, killing three and wounding at least 30, including a foreign tourist.

Nor is the Dalai Lama surprised. It was the 1959 uprising which precipitated his flight into exile in India. Since then he has campaigned tirelessly on behalf of his people. But until the 1987 disturbances, the world was content to turn a blind eye. Thanks largely to a celebrated visit to Lhasa in 1977 by the then US Ambassador to Peking, George Bush, the received opinion in the West was that China had brought about great improvements since it `liberated' Tibet in 1950. Thus the Tibe- tans, devout Buddhists though they most certainly are, have learned that violence is the only way to attract attention to their plight.

Nevertheless, His Holiness, who spoke to me here, the seat of his government in exile, responded to the first reports of rioting with customary equanimity. 'What can I say?' he asked. He sat, turning his rosary as we spoke. 'Naturally I am very sad. Sad at the continued killing but particularly sad to hear that it is mainly women and children that are involved.' Evidently hundreds of arrests were made on Sunday night after the initial demon- stration, leaving many families without their menfolk. 'Another reason to feel sorry,' he said, 'is that despite China's supposed new liberal outlook and open- ness, it is obvious that in terms of human rights, there is still this bullying and repres- sion. And yet they must realise that repres-

sion is counterproductive — unless of course their true aim is the total elimina- tion of the Tibetan people. If that is the case, I have nothing to say. But if it is not, it is clear that the only way forward is to cool down and then to sit down and try to win over the hearts of the Tibetan people.'

More than that, though, the Chinese need to sit down with the Dalai Lama, the one person who can assist them in such a 'hearts and minds' campaign. So far they have done a poor job of convincing Tibe- tans that Tibet is part of China. Not even the banning of Tibetan in schools or the destruction of all but 70 of 5,000 monaster- ies along with virtually all evidence of Tibet's unique religious culture could do that. But until the Chinese do sit down, the Dalai Lama feels that these demonstra- tions (which are illegal because they are 'anti-state') are 'the only way to alert both the Chinese government and the outside world to the reality of the situation'.

As far as negotiations are concerned, His Holiness has already indicated that he is ready to talk. In June last year, he made a statement to the European Parliament in Strasbourg suggesting that he could accept what would in effect be Chinese sovereign- ty, at least in the short term. In response to this, Peking announced that it would be prepared to meet a Tibetan exiles' delega- tion at a place of the Dalai Lama's choos- ing. However, the 'Strasbourg Statement' could not be a basis for talks. The Dalai Lama chose Geneva. Initial discussions were scheduled for January of this year. But then the Chinese began to raise objections. They would not discuss inde- pendence. They could not accept a fore- igner (a Dutch-born international lawyer) as a member of the team. Then they would not speak to any member of the Kashag, the Dalai Lama's cabinet. Finally, they would not meet anyone who had ever called for Tibetan independence.

So it is not surprising that the Dalai Lama should feel frustration in addition to sadness. 'Personally, I have made such effort to find a basis for compromise with the Chinese. But so far, despite their professed willingness, they have found themselves unable to talk. I feel that I have done everything possible.' But what makes the tragedy of Chinese and world indiffer- ence so poignant is the inflexible stand that 'What was the name of that obedience school?' he takes on violence. Could he ever condone it, I asked? 'Never. Not under any circumstances. I have deep admiration for the great courage and determination of the demonstrators. Most of them will certainly die for what they are doing, But as a Buddhist, I cannot support violence. Even When they are being fired upon, people must not retaliate violently. Of course I realise that this is very difficult. But it is also logical. For although the individual life Of a Tibetan is hot worth more than the individual life of one Chinese, we cannot afford to lose lives. They can. There are only six million Tibetans whereas there are a billion Chinese. Nor should we be angry at therm We should pray for the Chinese dead as Well as our own.'

Critics — of whom there are Plenty even among the Tibetans in exile — say that by rejecting violence the Dalai Lama is en- couraging the Chinese to play for time. After all, when he dies, it will be at least 18 years before a successor can assume tein- poral power. (According to Tibetan Buddhist principles, succession is by rein- carnation of the Dalai Lama's soul into a flew body.) In the meantime, government , is by regency. 'But this is childish thinking,' he said. 'The Problem will not go away With My death.' Besides, it would be wrong to assume that an infant Dalai Lama is any less revered than an adult. He remains throughout, the focus of all hope and aspirations of the Tibetan people. AS to the suggestion that his successor might be borh in Tibet, even if the present Dalai Lama dieg in India, he did not equivocate. The very purpose of reincatnation is to fulfil the previous life. So if I die outside Tibet, I • will be reborn outside Tibet. That's only common sense.'

It must be awkward for the Chinese to face an apparently indestructible lead- ership, coupled with a populace whom even four decades of oppression has not conquered. Awkward too for the Western world which is so keen to appease China for economic reasons.

Of the Dalai Lama's three most hoped- for allies (Britain, the United States and In- dia), the leaders of two have recently been to Peking. But Rajiv Gandhi virtually con- doned Chinese policy in Tibet whilst Presi- dent Bush chose to ignore the issue. It remains only for Britain to join the chorus of appeasers. Is it too much to hope that our Foreign Office will have the courage to condemn China for its shameless abuse of human rights in Tibet?

Previous page

Previous page