THE CHAIN OF COMMAND

Half a century ago Ivan Jelinek

was asked to broadcast his country's surrender to Germany

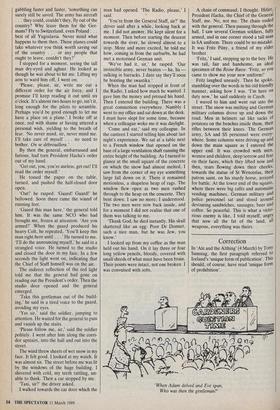

ON 14 March 1939 I was about to announce the regular late-night transmis- sion of the Czechoslovak short-wave sta- tion, Prague, when I was called to the telephone in the control room. 'This is General Staff,' said a man's voice at the other end. 'If you're an announcer we need you here as soon as possible.'

'But sir,' I said, 'the day-duty announcer hasn't arrived yet.'

'Never mind that,' the voice interrupted. 'You're an announcer, aren't you? You come straight away. I'm sending a car to pick you up.' The voice rang off. Sure enough, an NCO in a brown leather jacket rushed into the hall almost as soon as I got downstairs. 'Hurry please, my orders are to get you there yesterday.' I had little time to absorb the scene once inside the operations room at the General Staff building, an anguished purgatory at the best, a low-ceilinged room, suffocating- ly hot, crowded, noisy, filled with dense cigarette smoke, officers talking at the top of their voices or silent, some with jackets open at the neck, some unbuttoned, some in short sleeves, revealing a few thin figures but mostly paunches. All had sweat running down their faces. And the smoke! That was perhaps, I thought for a moment, why the eyes of a tall officer were full of tears. But the next moment I realised that the officer, his coat undone, was crying.

'I'm the Chief of Staff, General Fiala,' the officer said. 'I need you, you'll be doing some announcing for me. The Ger- man army has just begun to occupy the country. I had a phone call from Berlin, from President Hacha himself. He's at the Fiihrer's office. He spoke to me in person. And as Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces he dictated an order, to lay down our arms, to stay in barracks, to offer no resistance, not to destroy any army property, to leave everything intact, and await further orders.'

By then the general had taken me along the corridor and down some stairs.

'And you are required to read the President's order to the armed forces every ten minutes from now on until six in the morning, when the Wehrmacht will have occupied Prague. Here, take it, here is the order in writing. I took the President's dictation down myself, with some difficul- ty, I must say. The President kept pausing, he was almost inaudible from time to time, as if fainting. So here you are.'

General Fiala produced an octavo sheet, hand-written with a violet ink pencil, a word or two smeared, blotted, still wet.

The long corridor curving to the right was in the basement, but through a window I could see a piece of flat ground lit by a rapidly growing bonfire. In its light, through the agitated curtain of snowflakes, I could see human figures running back and forth, men throwing armfuls of files on the fire.

'The Second Bureau's burning its files,' the general said, as if it were an everyday occurrence. Then he stopped by a cubicle that jutted out from the wall. There was a normal studio light over the usual heavy door. The general opened the door and beckoned me in. The studio had a small desk, some chairs and on the table the usual English microphone. The general turned to me.

'Sit down and get ready,' he comman- ded.

For a moment a surge of anger and despair almost blinded me.

'General,' I said searching for words, gabbling faster and faster, 'something can surely still be saved. The army has aircraft . . . they could, couldn't they, fly out of the country? Why leave them for the Ger- mans? Fly to Switzerland, even Poland. . . best of all Yugoslavia. Never mind what happens to them then. Those planes could take whatever you think worth saving out of the country . . or any people that ought to leave, couldn't they?' , I stopped for a moment, seeing the tall man dry-eyed and aghast. He looked as though he was about to hit me. Lifting my arm to ward him off, I went on.

'Please, please, sir, write me out a different order for the air force, • and I promise I'll keep reading it out until six o'clock. It's almost two hours to go, isn't it, king enough for the pilots to scramble. Perhaps you'd be good enough to let me have a place on a plane.' I broke off at once, red with shame at having uttered a personal wish, yielding to the breath of fear. 'No never mind, sir, never mind me. I'll take care of myself . . . no need to bother. On se debrouillera.'

By then the general, embarrassed and furious, had torn President Hacha's order out of my hand.

`Get out, you, you're useless, get out! I'll read the order myself.'

He tossed the paper on the table, turned, and pushed the half-closed door Open.

'Out!' he rasped. 'Guard! Guard!' he bellowed. Soon there came the sound of running feet.

'Guard this man here,' the general told him. It was the same NCO who had brought me, frozen at attention. 'Are you armed?' When the guard produced his heavy Colt, he repeated, 'You'll keep this man right here until . . .' He turned to me. 'I'll do the announcing myself,' he said in a strangled voice. He turned to the studio and closed the door in my face. In a few seconds the light went on, indicating that the Chief of Staff himself was on the air.

The indirect reflection of the red light told me that the general had gone on reading out the President's order. Then the studio door opened and the general emerged.

'Take this gentleman out of the build- ing,' he said in a tired voice to the guard, avoiding my eyes.

'Yes sir,', said the soldier, jumping to attention. He waited for the general to pass and vanish up the stairs.

'Please follow me, sir,' said the soldier politely. I Went after him along the corri- dor upstairs, into the hall and out into the street.

The wind threw sheets of wet snow in my face. It felt good. I looked at my watch. It was almost six. The street before me was lit by the windows of the huge building. I shivered with cold, my teeth rattling, un- able to think. Then a car stopped by me.

'Taxi, sir?' the driver asked.

I walked towards the car door which the man had opened. 'The Radio, please,' I said.

'You're from the General Staff, sir?' the driver said after a while, looking back at me. I did not answer. He kept silent for a moment. Then before starting the descent towards the river, he slowed almost to a stop. More and more excited, he told me how, coming in from the surburbs, he had met a motorised German unit.

`We've had it, sir,' he rasped. `Our invincible army, never beaten — ha, ha — sulking in barracks. I dare say they'll soon be hoisting the swastika.'

When the man had stopped in front of the Radio, I asked how much he wanted. I gave him the Money and pressed his hand. Then I entered the building. There was a great commotion everywhere. Numbly I went to my office and sat down at thedesk. I muSt have slept. for some time, because when a colleague woke me it was daylight.

'Come and eat,' said my colleague. In the canteen I started telling him about last night's experience. We sat at a table next to a French window that opened On the base of a large ventilation shaft running the entire height of the building. As I turned to glance at the small square of the concrete on which the show had almost melted, I saw from the corner of my eye something large fall down on it. There it remained motionless, a shapeless heap of rags. The window flew open as two men 'rushed through to the heap on the concrete. They bent down. I saw no more; I understood. The two men were now back inside, and for a moment I did not realise that one of them was talking to me.

'Thank God, he died instantly. His skull shattered like an egg. Poor Dr Donnet, such a nice man, but he was Jew, you know.'

I looked up from my coffee as the man held out his hand. On it lay three or four long yellow pencils, bloody, covered with small shreds Of what must have been brain. Their Points were intact, not one broken. was convulsed with sobs. A chain of command, I thought. Hitler, President Hacha, the Chief of the General Staff, me. No, not me. The chain 'ended with the general. Then passing through the hall, I saw several German soldiers, fully armed, and in one corner stood a tall man in SA uniform. There could be no mistake. It was Fritz Pilny, a friend of my elder brother.

`Fritz,' I said, stepping up to the boy. He was tall, fair and handsome, an ideal specimen of the Reine Rasse. `Fritz, so you came to show me your new uniform!'

Fritz laughed uneasily. Then he spoke, stumbling over the words in hiS old friendly manner, asking how I was. 'I'm here on duty now,' he said suddenly in Czech.

I waved to him and went out into the street. The snow was melting and German military columns drove up and down the road. Men in helmets sat like sacks of potatoes on the benches inside them, their rifles between their knees. The German army, SA and SS personnel were every- where. Some columns were driving up and down the main square as I entered the upper end. It was crowded with -men, women and children, deep Sorrow.and fear on their faces, which they lifted now and then,. tears flowing down their cheeks, towards the statue of St Wenceslas, their patron saint, on his sturdy horse, arrayed for battle. At the lower end of the square, where there were big cafés and automatic vending machines, German military and police personnel sat and stood around devouring sandwiches, sausages, beer and coffee. So peaceful. This is what a victo- rious enemy is like, I told myself, angry that how all the fat of the land, all weapons, everything was theirs.

'When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then the gentleman?'

Previous page

Previous page