NOW FOR THE GOOD BOOZE

Memories of a beer hunter

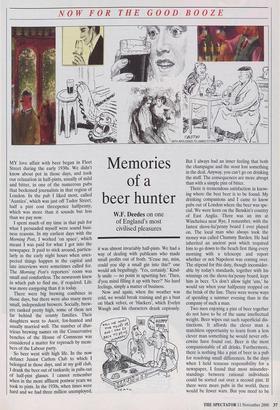

W.F. Deedes on one of England's most civilised pleasures MY love affair with beer began in Fleet Street during the early 1930s. We didn't know about pot in those days, and took our relaxation in half-pints, usually of mild and bitter, in one of the numerous pubs that beckoned journalists in that region of London. In the pub I liked most, called `Aunties', which was just off Tudor Street, half a pint cost threepence halfpenny, which was more than it sounds but less than we pay now. I spent much of my time in that pub for what I persuaded myself were sound busi- ness reasons. In my earliest days with the Morning Post, I worked 'on space', which meant I was paid for what I got into the newspaper. It paid to stick around, particu- larly in the early night hours when unex- pected things happen in the capital and late interviews were sometimes called for. The Morning Post's reporters' room was small and comfortless. The newsroom knew in which pub to find me, if required. Life was more easygoing than it is today. There were big brewing combines in those days, but there were also many more small, independent brewers. Socially, brew- ers ranked pretty high, some of them not far behind the county families. Their daughters went to Ascot, fox-hunted and usually married well. The number of illus- trious brewing names on the Conservative benches of the House of Commons was considered a matter for reproach by mem- bers of the Labour party. So beer went with high life. In the now defunct Junior Carlton Club to which I belonged in those days, and at my golf club, I drank the beer out of tankards; in pubs out of half-pint glasses. I cannot remember when in the more affluent postwar years we took to pints. In the 1930s, when times were hard and we had three million unemployed, it was almost invariably half-pints. We had a way of dealing with publicans who made small profits out of froth. `S'cuse me, miss, could you slip a small gin into this?' one would ask beguilingly. 'Yes, certainly.' Kind- ly smile — no point in upsetting her. 'Then, d'you mind filling it up with beer?' No hard feelings, simply a matter of business.

Now and again, when the weather was cold, we would break training and go a bust on black velvet, or 'blackers', which Evelyn Waugh and his characters drank copiously. But I always had an inner feeling that both the champagne and the stout lost something in the deal. Anyway, you can't go on drinking the stuff. The consequences are more abrupt than with a simple pint of bitter.

There is tremendous satisfaction in know- ing where the best beer is to be found. My drinking companions and I came to know pubs out of London where the beer was spe- cial. We were keen on the Benskin's country of East Anglia. There was an inn at Winchelsea near Rye, I remember, with the fastest shove-ha'penny board I ever played on. The local man who always took the money was called Chummy Barden. He had inherited an ancient post which required him to go down to the beach first thing every morning with a telescope and report whether or not Napoleon was coming over. The stipend for this duty, though inconsider- able by today's standards, together with his winnings on the shove-ha'penny board, kept him in beer. 'Us don't allow tight 'uns,' he would say when your halfpenny stopped on the brink of the line. There were worse ways of spending a summer evening than in the company of such a man.

Two men enjoying a pint of beer together do not have to be of the same intellectual weight. Beer wipes out such superficial dis- tinctions. It affords the clever man a matchless opportunity to learn from a less clever man something he would never oth- erwise have found out. Beer is the most companionable of all drinks. Furthermore, there is nothing like a pint of beer in a pub for resolving small differences. In the days when I held tenuous responsibility for a newspaper, I found that most misunder- standings between rational individuals could be sorted out over a second pint. If there were more pubs in the world, there would be fewer wars. But you need to be

NOW FOR THE GOOD BOOZE

under the roof of a landlord who knows how to keep beer well, without too much gas. I am allergic to gassy beers. And hav- ing to send back a cloudy pint interrupts the flow of intercourse. Keeping good beer calls for experience and taking pains.

The war years were hard for beer- drinkers. When war ended in my corner of Germany, we extravagantly sent three-ton lorries to France for champagne, because we'd won and, bottles being chronically short, you could exchange a couple of emp- ties for a full bottle. I drank the stuff in our mess because there was nothing else; but I would have exchanged a bottle of Krug for a pint of bitter. Later, I came to know and respect German lager. China, incidentally, has imported a German brewery and knows how to make the stuff impressively well.

When things settled down after the war, I took to keeping a small barrel of beer in my cellar at home. If you kept it at the right temperature and made sure that the bung was always replaced tightly, there was little wastage. Then our local brewery, Shepherd Neame of Faversham, came up with bitter in a polypin, which held about four and a half gallons, and was simpler than a barrel.

Ideally, I enjoy bitter best out of a tankard, particularly if it's pewter. But it is never worth making a song and dance about it. A pint of beer drunk solo or in company tastes best when you feel on good terms with yourself. It is not quite as good if you have just had an altercation with someone behind the bar who insists that all the tankards hanging up are privately owned by the pub's regular customers.

Now and again, breweries celebrate Christmas or some anniversary of their own by producing a special ale. It will almost certainly be a point or two up on the aver- age strength of bitter and I am wary of it outside the home. Our head — and blad- der — for beer varies according to age. After you qualify for a bus-pass, stay with beer of the same strength.

Early in my days as a parliamentary can- didate, a member of an otherwise rather stuffy local committee in a small town offered to take me on a pub-crawl. He ran a garage, and was the token artisan who in those days Tories thought it right to bring into the fold. There were, I remember, 12 pubs and in each of them we drank half a pint of beer. Well short of William Hague's score, but enough. Three hours later, we met the local committee for a final chaser and to report progress. Slightly pissed, I slapped the chairman on the back and gave the woman vice-chairman, who was quite good-looking, a rapturous kiss. They were very much taken aback. Silly old so-and-sos, I thought, and felt contemptuous of their sobriety. If you are going to behave badly, beer's the right stuff to do it on. Oh, the joy

Previous page

Previous page