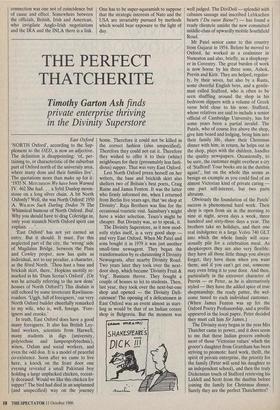

THE PERFECT THATCHERITE

Timothy Garton Ash finds

private enterprise thriving in the Divinity Superstore

East Oxford `NORTH Oxford', according to the Sup- plement to the OED, is now an adjective. The definition is disappointing: 'of, per- taining to, or characteristic of the suburban part of Oxford north of the university area, where many dons and their families live'. The quotations more than make up for it: `1935 N. MITCHISON We have been Warned IV. 462 She had. . . a Sybil Dunlop moon- stone on a long silver chain. A bit North Oxfordy? Well, she was North Oxford! 1950 A. WILSON Such Darling Dodos 79 The Whimsical humour of North Oxford. Ibid. Why you should have to drag Coleridge in, only your staunch North Oxford spirit can explain. .

`East Oxford' has not yet earned an entry. But it should. It must. For this neglected part of the city, the 'wrong' side of Magdalen Bridge, between the Plain and Cowley proper, now has quite as individual, not to say peculiar, a character, as the feted North. 'Thou hast a base and brickish skirt, there,' Hopkins snottily re- marked in his 'Duns Scotus's Oxford'. (Or was he actually referring to the new dons' houses of North Oxford?) This disdain is still echoed by some inveterate Rawlinson- roaders. `Uggh, full of foreigners,' our very North Oxford builder cheerfully remarked to my wife, who is, well, foreign. 'Fore- igners and crooks.'

In truth, East Oxford does have a good many foreigners. It also has British Ley- land workers, scientists from Harwell, many students in digs (university, polytechnic and lumpenpolytechnic), winos, Oxfam and social workers, and even the odd don. It is a model of peaceful co-existence. Soon after we came to live here, a knock on the front door one evening revealed a small Pakistani boy holding a large unplucked chicken, recent- ly deceased. Would we like this chicken for supper? The bird had died in an unplanned (and unspecified) way on the journey home. Therefore it could not be killed in the correct fashion (also unspecified). Therefore they could not eat it. Therefore they wished to offer it to their (white) neighbours for their (presumably less fasti- dious) supper. That was very East Oxford.

Lest North Oxford preen herself on her writers, the base and brickish skirt also shelters two of Britain's best poets, Craig Raine and James Fenton. It was the latter who firmly informed me, when I returned from Berlin five years ago, that 'we shop at Divinity'. Raja Brothers was fine for the occasional touristic visit. Sainsbury's might have a wider selection. Tesco's might be cheaper. But Divinity was, so to speak, it.

The Divinity Superstore, as it now mod- estly styles itself, is a very good shop and very East Oxford. When Mr Patel and sons bought it in 1979 it was just another small-time newsagent. They began the transformation by re-christening it Divinity Newsagents, after nearby Divinity Road. Two years later they took over the next- door shop, which became 'Divinity Fruit & Veg'. Business throve. They bought a couple of houses to let to students. Then, last year, they took over the next-but-one shop and opened — the Divinity Deli- catessen! The opening of a delicatessen in East Oxford was an event almost as start- ling as would be that of an Indian corner shop in Belgravia. But the moment was well judged. The DiviDeli — splendid with cabanas sausage and inscribed Lebkuchen hearts (`Du susse Mend') — has found a ready clientele amidst the new committed middle-class of upwardly mobile Southfield Road.

Mr Patel senior came to this country from Gujarat in 1954. Before he moved to Oxford, he worked as a coalminer in Nuneaton and also, briefly, as a shopkeep- er in Coventry. The great burden of work is now borne by his three sons, Ashok, Previn and Kirit. They are helped, regular- ly, by their wives, but also by a Rasta, some cheerful English boys, and a gentle- man called Stafford, who is often to be seen shuffling around the shop in his bedroom slippers with a volume of Greek verse held close to his nose. Stafford, whose relatives are said to include a senior official of Cambridge University, has for some years been a partial invalid. The Patels, who of course live above the shop, give him board and lodging, bring him into their family life, share their Christmas dinner with him; in return, he helps out in the shop, plays with the children, handles the quality newspapers. Occasionally, to be sure, the customer might overhear a cry of 'Stafford! Your books are in the dustbin again!', but on the whole this seems as benign an example as you could find of an almost Victorian kind of private caring one part self-interest, but two parts altruism.

Obviously the foundation of the Patels' success is phenomenal hard work. Their shop is open from six in the morning to nine at night, seven days a week, three hundred and sixty-three days a year. The brothers take no holidays, and their one real indulgence is a large Volvo 740 GLT into which the whole family will occa- sionally pile for a celebration meal. As shopkeepers they are also very flexible: they have all those little things you always forget; they have them when you want them; and if you can't get out, someone may even bring it to your door. And then, particularly in the extrovert character of Previn — or Peter, as he is alternatively styled — they have the added spice of true shopmanship: the ready patter, the wel- come tuned to each individual customer. (When James Fenton was up for the Oxford Poetry Professorship, and a profile appeared in the local paper, Peter decided they must call him Sir James.) The Divinity story began in the year Mrs Thatcher came to power, and it does seem to me that these Indian grocers embody most of those 'Victorian values' which the grocer's daughter from Grantham has been striving to promote: hard work, thrift, the spirit of private enterprise, the priority for the family (Peter will send his daughter to an independent school), and then the truly Dickensian touch of Stafford retrieving his Liddell and Scott from the dustbin before joining the family for Christmas dinner. Surely they are the perfect Thatcherites?

Previous page

Previous page