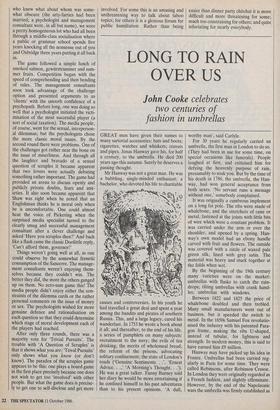

UNSCRUPULOUS WINNERS

Adrian Furnham finds too much

is revealed about oneself by a new board game

I HAVE often thought that the 'board' in `board games' has always been misspelt, and would more honestly read 'bored games'. 'Trivial Pursuits', it is said, was Invented' by two Canadians on holiday in Spain. Those monotonous long hot days presumably induced the inventors to chal- lenge each other's depths of irrelevant and humdrum 'knowledge' and base a game on it. Some of us wished that the game had never left the Costa del Crime where it belongs rather than forcing itself into the drawing rooms of Dulwich or the patios of Pimlico.

It is no accident that children, young adolescents and elderly people are encour- aged to play and enjoy bored games. Being socially inadequate in the case of the former, and egocentric in the case of the latter, simple card or competitive board games help to structure social intercourse. Unable to indulge in amusing anecdotes or sagacious repartee, they enjoy choosing between answering questions on geogra- phy or sport in order to edge their plastic counter round the board to fill the pie.

Adults, I contend, play bored games when they are thrown (often involuntarily) into the company of others (usually rela- tives) and discover that Sartre was right hell is other people. That is why one plays these games at Christmas and on holidays, and particularly on board (bored?) ship. It is true that God gave us our friends and the devil our relations, and hence the useful- ness of games when one is forced to endure one's relatives. Small talk becomes smal- ler; the idea of building hotels on Vine Street, or owning the electricity works or all the stations, becomes an increasingly attrractive alternative.

Recently, the media have heralded the release of a new game which, the manufacturers no doubt hope, will prove as successful as 'Trivial Pursuits'. The game, 'A Question of Scruples', is piled high in Hamleys and the like, waiting for the expected rush. What is its appeal? (This question has probably inspired a lot of market research, as well as sleepless nights on the part of would-be get-rich- quick inventors.) Doing what social scientists call partici- pant research, I decided to investigate this game. It emerges as moderately simple, and neither two glasses of chablis nor being congenitally hard of thinking prevents one from understanding the rules. Strictly speaking it is a card game, much like poker, which leaves one wondering why one has to pay f15 for what is, after all, no more than a couple of packs of cards. Each player gets three types of cards — the Q(uestion) or moral dilemma cards, the A(nswer) cards (with an equal probability of 'yes', `no' and 'depends') and a vote card.

The aim is to get rid of all your Question (ethical teaser) cards and one does so by nominating a (any other) player, reading out the dilemma and trust- ing that he or she will give an answer matching your unrevealed answer card. So, for instance, one would first glance at one's answer card, which, say, is 'yes', then turn to a well-known scoundrel and pathologic- al liar in the group and pose your question: `The Inland Revenue has given you a large tax refund by mistake. Do you inform them?' If he says 'yes' you lose the card (your aim), but if he says `no' or 'depends' you have to draw both another Question card and a new Answer card.

That would be all very well if one was at a Quaker conference on conscience ex- amination, and would give enough mater- ial for a moral philosopher to be going on for at least two dreary textbooks or Radio 3 talks. But there are two vitally important caveats. The first is crucial: you may lie, indeed the rules almost encourage it. Therefore, you don't have to report on your likely response to the dilemma, or indeed your actual moral judgment of the dilemma. Your aim is to anticipate what the asking player expects you to say, and then give a different response. So it becom- es a game of bluff and double bluff — a sort of ethical poker. The second caveat gives you the liberty of challenging the response of the answering player whether the answer matches or not. The answering player wins by convincing the majority of the players that his reply is sincere (truth- ful, likely etc) while the challenger wins by convincing them that it is not. Everybody votes.

This, of course, allows for the possi- bility of rationalisation, impression- management and argument (i.e. more like a normal dinner party) but, more impor- tant, the possibility of ganging up on others. One need not necessarily vote on the quality (or quantity) of the argument — that is not in the spirit of the game. One is not one of 12 good men and true, or vetted for impartiality and disinterest simply sozzled, bored and cantankerous and delighted to find a way to punish an unpopular guest. So the game may resem- ble that other most English of sports - croquet — as one may conspire quite `innocently and innocuously' to prevent someone from winning.

The success of the game depends, in large part, on the salience and subtlety of the dilemma Question cards (the question of scruples) and the personalities of the players. There are 259 dilemma cards which cover a range of ethical, moral and legal issues. There are many about sex, as one may expect (`Your spouse does not satisfy your sexual needs. You meet some- one who might. Do you get involved?'); some about nepotism and favouritism CA friend who needs a job applies to your business. Someone who is better qual- ified also applies. Do you hire your friend?'); many about money, especially that grey area between tax avoidance and evasion (`You and your spouse are dining in an expensive restaurant. Your waiter forgets to add drinks to the bill. Do you tell him?').

There are also classic moral issues — some of which are political (`You are a Labour councillor and your child wins a public school scholarship. Do you let him take up the offer?'); others of which are personal (`You hear a conversation of two strangers when you pick up the phone. Do you listen to it?'). Many are about white lies and many about asserting one's person- al and legal rights. Many are tediously trivial and would not over-extend a second form debate (`You are waiting at a red light at 4 a.m. There isn't a car in sight. Do you go through the red light?').

The second crucial feature to make the game work is, of course, the players. Not only is it essential that they are articulate, but ideally they should know one another. This is crucial for the meta-perception that the task demands: i.e. perception (my perception of you), meta perception (my perception of your perception of me); meta-meta-perception (my perception of your perception of my perception of you). All very R. D. Laing! When I played there were six of us: two highly successful, avaricious management consultants who took longer to dress casually (i.e. out of uniform) for the party than for work; two rather shabby academic-type psycholog- ists, neither with a particularly clinical bent; and two 'arty-farty' creative media people. Although the precise sociometry of who knew what about whom was some- what obscure (the arty-farties had been married; a psychologist and management consultant were, in all but name), we were a pretty homogeneous lot who had all been through a middle-class socialisation where a public or grammar school spends five years knocking all the nonsense out of you and Oxbridge three years putting it all back in.

The game followed a simple lunch of smoked salmon, gewiirztraminer and sum- mer fruits. Competition began with the speed of comprehending and then bending of rules. The management consultants soon took advantage of the challenge option and presented arguments to us 'clients' with the smooth confidence of a psychopath. Before long, one was doing so well that a psychologist initiated the victi- misation of the most successful player (a sort of social taxation). The media people, of course, went for the sexual, interperson- al dilemmas; but the psychologists chose the more classic moral issues. By the second round there were problems. One of the challenges got rather near the bone on the issue of miserliness. And through all the laughter and bravado of a sexual question of scruples it became apparent that two lovers were actually debating something rather important. The game had provided an arena to discuss openly and publicly private doubts, fears and anx- ieties. It also soon became apparent that Shaw was right when he noted that an Englishman thinks he is moral only when he is uncomfortable. One could almost hear the voice of Pickering when the surprised media specialist turned to the clearly smug and successful management consultant after a clever challenge and asked 'Have you scruples then?' And back like a flash came the classic Doolittle reply, `Can't afford them, governor!'

Things weren't going well at all, as one could observe by the somewhat frenetic consumption of the Sancerre. The manage- ment consultants weren't enjoying them- selves because they couldn't win. The better they did, the more the others ganged up on them. No zero-sum game this! The media people didn't enjoy either the con- straints of the dilemma cards or the rather personal comments on the issue of money or sex. The psychologists wished for more genuine defence and rationalisation on each question so that they could determine which stage of moral development each of the players had reached.

After only three rounds, there was a majority vote for 'Trivial Pursuits'. The trouble with 'A Question of Scruples' is that it shows what you are; `Trival Pursuits' only shows what you know (or don't know). The paradox of the scruples game appears to be this: one plays a board game in the first place precisely because one does not wish to get too 'involved' with other people. But what the game does is precise- ly to get one to self-disclose and get more involved. For some this is an amusing and unthreatening way to talk about taboo topics; for others it is a glorious forum for public humiliation. Rather than being easier than dinner party chitchat it is more difficult and more threatening for some; much too constraining for others; and quite infuriating for nearly everybody.

Previous page

Previous page