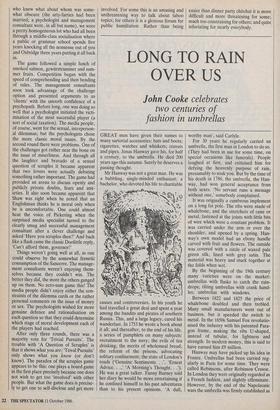

LONG TO RAIN OVER US

John Cooke celebrates

two centuries of fashion in umbrellas

GREAT men have given their names to many sartorial accessories: hats and boots; cigarettes, watches and whiskers; cravats and pipes. Jonas Hanway gave his, for half a century, to the umbrella. He died 200 years ago this autumn. Surely he deserves a passing thought.

Mr Hanway was not a great man. He was a bubbling, single-minded enthusiast; a bachelor, who devoted his life to charitable causes and controversies. In his youth he had travelled a great deal and spent a year among the bandits and pirates of southern Russia. This, and a large legacy, cured his wanderlust. In 1753 he wrote a book about it all; and thereafter, to the end of his life, a series of pamphlets on many subjects: recruitment to the navy; the evils of tea drinking; the merits of wholemeal bread; the reform of the prisons, advocating solitary confinement; the state of London's roads (`Genuine Sentiments. . 'Ernest Advice. . .,"A Morning's Thought. .

He was a great talker. Fanny Burney told her diary he would be more entertaining if he confined himself to his past adventures than to his present opinions. 'A dull, worthy man', said Carlyle.

For 30 years he regularly carried an umbrella, the first man in London to do so. (They had been in use for some time, on special occasions like funerals). People laughed at first, and criticised him for defying the heavenly purpose of rain, presumably to soak you. But by the time of his death in 1786, the umbrella, the Han- way, had won general acceptance from both sexes. 'No servant runs a message without one,' somebody complained.

It was originally a cumbrous implement on a long fat pole. The ribs were made of whalebone, and the stretchers of cane or metal, fastened at the joints with little bits of wire which were a constant problem. It was carried under the arm or over the shoulder, and opened by a spring. Han- way's own model had an ebony handle carved with fruit and flowers. The outside was covered with a circle of waxed pale green silk, lined with grey satin. The material was heavy and stuck together at the folds when wet.

By the beginning of the 19th century many varieties were on the market: umbrellas with flasks to catch the rain- drops; tilting umbrellas with crank hand- les; umbrellas with windows.

Between 1822 and 1825 the price of whalebone doubled and then trebled. Many small manufacturers went out of business, but it speeded the switch to metal. In the 1850s Samuel Fox revolutio- nised the industry with his patented Para- gon frame, making the ribs U-shaped, instead of tubular, for lightness and strength. In modern money, this is said to have earned him £9 million.

Hanway may have picked up his idea in France. Umbrellas had been carried reg- ularly in Paris for some time. They were called Robinsons, after Robinson Crusoe. In London they were originally regarded as a French fashion, and slightly effeminate. However, by the end of the Napoleonic wars the umbrella was firmly established as a British symbol, and consequently quite out of fashion in Paris. Pitt said that, to help pay for the war, he had considered taxing them and ordering the bishops to pray for rain.

Umbrellas were popular in the army. Wellington put a stop to it all in 1813 at Bayonne. He said it looked unmilitary for officers to use them on the battlefield. The duke's orders had been forgotten two years later at Waterloo. A French general de- scribed an English cavalry charge: 'They closed their umbrellas, hung them on their saddles, drew their sabres and threw them- selves on our Chasseurs'. Punch later suggested the troops should also be pro- tected, and have umbrellas fixed to their guns.

The price of an umbrella during most of the 19th century ranged, in modern money, between £10 and f60, much the same as today. Services grew up, both for repairs and for ironing out and re-rolling after a shower; men's pencil-tight rolled umbrellas came into fashion about 1880.

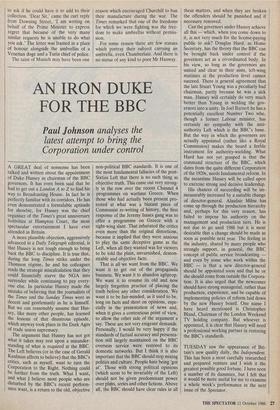

The London Umbrella Company opened stalls all over central London to hire umbrellas at £1.20 (modern money) for three hours. You paid a deposit which was returnable when you brought back the umbrella to any convenient stall, like renting a car. There was an 'umbrella hospital' in Shoreditch with a joky tariff: restoring broken neck, new muscle, new spine, etc.

Royal patronage is well recorded. George IV had a pink one. Queen Victoria had one interlined with chain-mail, which is still extant, after an attempt on her life. Edward VII, when he was Prince of Wales, had a fleur-de-lys design round the cover. Edward VIII was photographed leaving Buckingham Palace under an umbrella. Mrs Simpson's help was sought to ask the King 'to be more careful in future as to how he is photographed'.

Perhaps the most famous of all is the umbrella that Chamberlain took to Munich. Where is it now? The curator of the Museo dell' Ombrello near Stresa wrote to ask if he could have it to add to their collection. 'Dear Sir,' came the curt reply from Downing Street, 'I am writing on behalf of the Prime Minister to express regret that because of the very many similar requests he is unable to do what you ask.' The letter was framed in a place of honour alongside the umbrellas of a Venetian doge and a Turin chief of police.

The taint of Munich may have been one reason which encouraged Churchill to ban their manufacture during the war. The Times remarked that one of the freedoms for which we were fighting was the free- dom to make umbrellas without permis- sion.

For some reason there are few statues which portray their subject carrying an umbrella, even Chamberlain. And there is no statue of any kind to poor Mr Hanway.

Previous page

Previous page