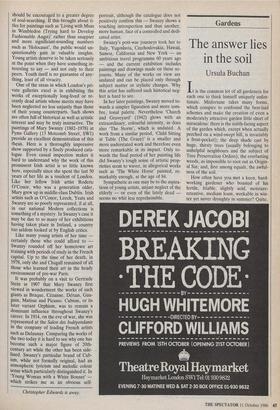

Gardens

The answer lies in the soil

Ursula Buchan

How often have you met a keen, hard- working gardener who boasted of his fertile, friable, slightly acid, moisture- retentive, medium loam, workable in win- ter yet never droughty in summer? Quite. I am obviously letting the side down when I admit openly that I garden on a good soil, a sandy loam. Let me hastily assure you that it is not perfect for it dries out too quickly in summer. Nevertheless, it is a village soil, roamed for many years, I imagine, by the family pig and therefore quite fertile for one so quick-draining. There is, I know, something a little vulgar, or certainly in questionable taste, about owning up to that; it smacks of a desire to grind the faces of other gardeners into their stiff, unworkable clays.

I am one of the lucky ones but, however legitimate the complaints made by garden- ers about their ground, it is important that they do not turn away in unhappy resigna- tion and concentrate their efforts on the `simply blissful' flowers alone, for that simple blissfulness has a great deal to do with the dirt in which the flowers grow. I rather admire people who embrace the subject of soil with enthusiasm, who feel at home with iron chelates and the collodial nature of humus, and will say without hesitation when asked where they garden: `We live on a band of greensand, over- laying gravel, at a pH of 5.5.' I consider it a useful accomplishment to be au fait with the constituents of one's soil; not to be boasted about, of course, but a source of quiet satisfaction, like knowing where to find the Travellers' Club without asking a taxi-driver.

A simple kit or meter will serve to test the acidity or alkalinity (pH) of the soil with acceptable accuracy; this is a facet of the subject about which no gardener should remain in ignorance, for some plants like rhododendrons are most par- ticular. There is not, in the long term, a great deal we can do to alter the pH so that we may grow plants which do not like what we have got, nor should we bother over- much (except by adding lime to an acid soil to improve the quality of cabbages). After all, the pH of the soil, and the plants that it supports, can be as firm indicators of place as vernacular architecture and should not be permanently transformed with the che- mical or organic equivalents of UPVC replacement windows and 'stone' cladding. Fortunately, plants know their place as well as any Victorian housemaid and so few calcifuge plants will survive healthily for long in a limy soil, however much peat is dug in to try to acidify it.

That said, it is possible to do much to improve the structure (and, to a lesser extent, the texture) of a soil. Texture refers to the proportions of the different-sized particles of sand, silt, clay, and organic matter in the . soil. A preponderance of large particles makes a light soil, and small particles a heavy one. Structure refers to the way in which the particles are aggre- gated together into 'crumbs'. A soil with good structure has large crumbs so that there are wide pores for oxygen and water to pass through. A sandy soil, consisting of many large particles which allow water to drain too quickly, is made more retentive by frequent digging in of compost or manure. Thin soils over chalk require the same treatment and the sub-soil should be forked over to enable the roots of plants to reach down to any available water. Even a clay which seems as difficult to get through as an episode of EastEnders can be light- ened in time by the persistent digging in, in autumn or early winter, of copious quanti- ties of grit or sand, ashes and well-rotted compost. There is comfort even in despair, for clay soils hold nutrients and water well and are therefore very fertile.

One may dedicate oneself to lesser things in life than the improvements of one's soil. It is honourable work, intellec- tually absorbing and physically tiring. A really heavy clay is certainly not to be wished on one's worst enemies, or not the older ones amongst them, but there are plenty of fine gardens made on the stickiest substrate. For example, the famous garden belonging to Beth Chatto at White Barn House, Elmstead Market in Essex has been developed over the last 30 years on a soil that was in places too heavy and waterlogged to be farmed. There is a sloping bank of pure clay, formed when a lake was excavated, which has been trans- formed into a successful flower border by the piling on top of masses of compost. Counting up misfortunes is agreeable, but anyone who has seen this garden may prefer in future to save their breath for the digging.

Previous page

Previous page