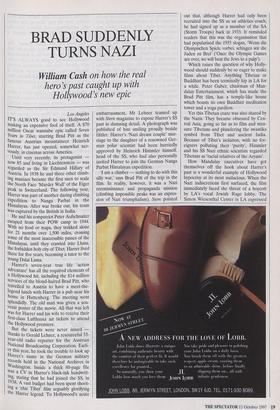

BRAD SUDDENLY TURNS NAZI

William Cash on how the real

hero's past caught up with Hollywood's new epic

Los Angeles IT'S ALWAYS good to see Hollywood making an expensive fool of itself. A $70 million Oscar wannabe epic called Seven Years in Tibet, starring Brad Pitt as the famous Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer, has just opened, somewhat ner- vously, in cinemas across America.

Until very recently, its protagonist — now 85 and living in Liechtenstein — was regarded as the Sir Edmund Hillary of Austria. In 1938 he and three other climb- ing maniacs became the first men to scale the North Face 'Murder Wall' of the Eiger peak in Switzerland. The following year, Harrer was part of another daring climbing expedition to Nanga Parbat in the Himalayas. After war broke out, his team was captured by the British in India.

He and his compatriot Peter Aufschnaiter escaped from their POW camp in 1944. With no food or maps, they trekked alone for 21 months over 1,500 miles, crossing some of the most inaccessible passes of the Himalayas, until they crawled into Lhasa, the forbidden holy city of Tibet. Harrer lived there for five years, becoming a tutor to the Young Dalai Lama.

Harrer's seven-year true life 'action adventure' has all the required elements of a Hollywood hit, including the $14 million services of the blond-haired Brad Pitt, who travelled to Austria to have a meet-the- legend lunch with Harrer in a pub near his home in Huttenberg. The meeting went splendidly. The old man was given a sou- venir poster of the movie. All that was left Was for Harrer and his wife to receive their first-class Lufthansa air tickets to attend the Hollywood premiere. But the tickets were never issued — thanks to Gerald Lehner, a resourceful 33- Year-old radio reporter for the Austrian National Broadcasting Corporation. Earli- er this year, he took the trouble to look up Harrer's name in the German military records held in the National Archives in Washington. Inside a thick 80-page file was a CV in Harrer's black-ink handwrit- ing, stating that he had joined the SS, in 1938. A vast budget had been spent shoot- ing a 'chic Tibet' film arguably glorifying the Harrer legend. To Hollywood's acute embarrassment, Mr Lehner teamed up with Stem magazine to expose Harrer's SS past in damning detail. A photograph was published of him smiling proudly beside Hitler. Harrer's 'Nazi dream couple' mar- riage to the daughter of a renowned Ger- man polar scientist had been hurriedly approved by Heinrich Himmler himself, head of the SS, who had also personally invited Harrer to join the German Nanga Parbat Himalayan expedition.

'I am a climber — nothing to do with this silly war,' says Brad Pitt of the trip in the film. In reality, however, it was a Nazi reconnaissance and propaganda mission (climbing impossible peaks was an expres- sion of Nazi triumphalism). Stem pointed out that, although Hauer had only been recruited into the SS as an athletics coach, he had signed up as a member of the SA (Storm Troops) back in 1933. It reminded readers that this was the organisation that had popularised the 1935 slogan, 'Wenn die Olympischen Spiele vorbei, schlagen wir die Juden zu Brei' ('Once the Olympic Games are over, we will beat the Jews to a pulp').

Which raises the question of why Holly- wood should suddenly be so eager to make films about Tibet. Anything Tibetan or Buddhist has been terminally hip in LA for a while. Peter Guber, chairman of Man- dalay Entertainment, which has made the Brad Pitt film, has a temple-like house which boasts its own Buddhist meditation tower and a yoga pavilion.

Yet this Tibetan craze was also shared by the Nazis. They became obsessed by Cen- tral Asia, going so far as to film and mea- sure Tibetans and plundering the swastika symbol from Tibet and ancient India. Because of Tibet's isolation, with no for- eigners polluting their 'purity', Himmler and his SS Nazi ethnic scientists regarded Tibetans as 'racial relatives of the Aryans'.

How Mandalay executives have got themselves off the hook about Harrer's past is a wonderful example of Hollywood hypocrisy at its most audacious. When the Nazi indiscretions first surfaced, the film immediately faced the threat of a boycott by LA's vocal Jewish Rage lobby. The 1 Simon Wiesenthal Center in LA expressed concern that casting a heart-throb movie star like Pitt in the role of a Nazi could turn the man into a hero and inadvertently 'whitewash the legacy of the Third Reich'. The centre's Rabbi Cooper said Harrer was suffering from Waldheimer's disease'.

Only last month, LA's Jewish Rage lobby became highly agitated when it was discovered that Leni Riefenstahl had made an unpublicised visit to receive an award at an LA film festival. Harrer was contracted to appear in a film Riefenstahl made about skiing in 1938. 'They sneaked her into town,' fumed Rabbi Cooper.

To placate LA's militant rabbi faction, a would-be diplomatic photo-opportunity meeting was set up in Vienna between the Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal and Herr Harrer. Wiesenthal was left unimpressed by Harrer's efforts to explain why he had kept his past hidden for 50 years (when the Austrian reporter Lehner dared to con- front Harrer on the subject in his house, he was thrown out). In a subsequent state- ment, Harrer spoke of the events of his youth as being the 'biggest aberration' in his life. For Rabbi Cooper, however, he remained 'arrogant, gutless' and insincere.

Meanwhile, how do you change a com- pleted $70 million epic when you awk- wardly find yourself with a diehard Nazi hero on your hands? The Mandalay pro- duction team answer is the addition of two last-minute voice-over dialogues that cure Harrer of his amnesia. One addition has Harrer suddenly remembering his secret past as he watches some war-mongering Chinese generals arrive before the 1950 invasion. 'I shudder to recall how once, long ago, I embraced the same beliefs, how at one time I was no different from these intolerant Chinese,' says Pitt, mournfully.

Next, Mandalay redrafted their market- ing campaign. In the 1952 introduction to the English edition of Seven Years in Tibet, the 1930s British travel writer Peter Flem- ing attested to Harrer's 'integrity of char- acter'. He wrote: 'I have not met Herr Harrer but, from the pages that follow, he emerges as a sensible, unassuming and very brave man, with simple tastes and solid standards.'

The movie's PR production notes prefer to describe Harrer as 'selfish and egotisti- cal'. Indeed, the ingenious line now cranked out by John Jacobs, Mandalay's head of marketing, is that Harrer was so egotistical and self-centred in his early life — until his supposed 'spiritual enlightenment' through the young Dalai Lama — that it is obvious he must have been a Nazi. 'Elmer is abso- lutely not a hero,' the screenwriter Becky Johnston stressed to me. 'He comes off as a badly damaged soul.'

'The movie is about what happened to him from 1939 and forward,' adds Jacobs. 'The fact that he was a Nazi only explains that the character had to change. This is a movie about guilt and remorse. It's about redemption, OK?'

But then, I ask, if Harrer truly did expe- rience a catharsis in Tibet, surely he would be a perfect poster boy to invite to the American premiere and appear on the Today show? 'In the end, he just didn't want to come,' replied Jacobs, ruefully. 'It's embarrassing for him, for everybody, OK? The bulk of his life, when you mea- sure 85 years, is pretty exemplary, .0K? Who he partied with in 1934, who knows?'

The bad news, however, is that the zeal- ous Gerald Lehner has been busy again. He is publishing a new article in the Austrian news magazine Profil that apparently proves Harrer has been quietly keeping up with many of his villainous best Nazi friends, including a formerly jailed war criminal who was involved with 'medical experiments' on prisoners at Auschwitz. Lehner says that Harrer last saw him in 1994.

The good news is that the September issue of the German climbing magazine Alpin will never reach LA news-stands. In an article entitled 'Heinrich Harrer und die SS', the world's most famous and respected living climber, Reinhold Mess- ner, has written of how Harrer has been holding onto his Nazi ideology. On televi- sion appearances with Harrer over the years, Messner says he never uttered a word of remorse.

But does all this really matter? The answer is that in America, where the line between history and movies is disturbingly blurred, it matters a great deal to the coun- try's almost Nazi-like politically correct thought police. 'The American world is totally black and white', says Jacobs, who says he could never defend Harrer for fear of negative box-office reaction.

In Europe, however, where there is still a happier distinction between movies, history and reality, nobody seems to care terribly about Herr Harrer's wicked past. Accord- ing to Lehner, the Nazi revelations have had little impact on Humes reputation in Austria. 'It was just a bad echo here,' he says. 'I got many letters, and they all said I shouldn't be hounding an old man. One said I should be put in the gas chamber.'

But Harrer's real crime is not anything he did as a gym coach, but that he commit- ted the atrocity of not using his celebrity limelight to castigate himself in the I- fucked-up, Hugh Grant talk-show confes- sion style. Rabbi Cooper said he was 'appalled' that Harrer had never used his fame to admit to his past. But then, can you honestly blame him?

The record of history, of course, will always be what Hollywood wants it to be. It will come as no surprise to learn that the movie's phoney ending, with Harrer proudly placing a Tibetan flag on a mountain peak he has climbed with his teenage son Peter, never happened. Harrer and his son, whom he had abandoned in 1939, never got on.

These days, marketing a sexy controversy (Mr Jacobs also masterminded the tumult over the Oliver Stone film JFK) is simply a smart way of turning a very costly film into a media event. And if that involves string- ing up the occasional old European legend, so much the better.

Previous page

Previous page