SETTLERS UNDER SIEGE

Con Coughlin reports on the Israelis

of Gaza, previously thrown out of Sinai, who are refusing to be dispossessed again

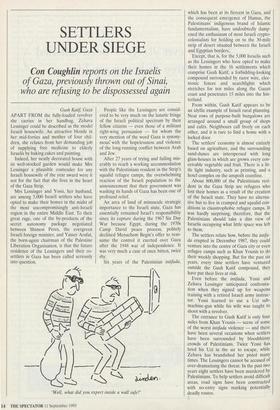

Gush Katif, Gaza APART FROM the fully-loaded revolver she carries in her handbag, Zehava Lessinger could be described as the model Israeli housewife. An attractive blonde in her mid-forties and mother of four chil- dren, she relaxes from her demanding job of supplying free medicine to elderly Israelis by baking cakes and painting.

Indeed, her neatly decorated house with its well-stocked garden would make Mrs Lessinger a plausible contender for any Israeli housewife of the year award were it not for the fact that she lives in the heart of the Gaza Strip.

Mrs Lessinger and Yossi, her husband, are among 5,000 Israeli settlers who have opted to make their homes in the midst of the most uncompromisingly anti-Israeli region in the entire Middle East. To their great rage, one of the by-products of the secret autonomy package negotiated between Shimon Peres, the evergreen Israeli foreign minister, and Yasser Arafat, the born-again chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organisation, is that the future residence of the Lessingers and their co- settlers in Gaza has been called seriously into question. People like the Lessingers are consid- ered to be very much on the lunatic fringe of the Israeli political spectrum by their fellow citizens — even those of a militant right-wing persuasion — for whom the very mention of the word Gaza is synony- mous with the hopelessness and violence of the long-running conflict between Arab and Jew.

After 27 years of trying and failing mis- erably to reach a working accommodation with the Palestinians resident in the Strip's squalid refugee camps, the overwhelming reaction of the Israeli population to the announcement that their government was washing its hands of Gaza has been one of profound relief.

An area of land of minuscule strategic importance to the Israeli state, Gaza has essentially remained Israel's responsibility since its capture during the 1967 Six Day War because Egypt, during the 1970s Camp David peace process, politely declined Menachem Begin's offer to reas- sume the control it exerted over Gaza after the 1948 war of independence. It was very much a case of once bitten, twice shy.

Six years of the Palestinian intifada, 'Well, what did you expect inside a wall safe?' which has been at its fiercest in Gaza, and the consequent emergence of Hamas, the Palestinians' indigenous brand of Islamic fundamentalism, have undoubtedly damp- ened the enthusiasm of most Israeli crypto- colonialists for holding on to the 30-mile strip of desert situated between the Israeli and Egyptian borders.

Except, that is, for the 5,000 Israelis such as the Lessingers who have opted to make their homes in the 16 settlements which comprise Gush Katif, a forbidding-looking compound surrounded by razor wire, elec- tronic fences and searchlights which stretches for ten miles along the Gazan coast and penetrates 15 miles into the hin- terland.

From within, Gush Katif appears to be an idyllic example of Israeli rural planning. Neat rows of purpose-built bungalows are arranged around a small group of shops and cafés. Neighbours call freely on each other, and it is rare to find a home with a locked door.

The settlers' economy is almost entirely based on agriculture, and the surrounding sand-dunes are interspersed with long glass-houses in which are grown every con- ceivable vegetable and fruit. There is a lit- tle light industry, such as printing, and a hotel complex on the unspoilt coastline.

About 800,000 of the Palestinians resi- dent in the Gaza Strip are refugees who lost their homes as a result of the creation of the Israeli state. They have no alterna- tive but to live in cramped and squalid con- ditions in claustrophobic refugee camps. It was hardly surprising, therefore, that the Palestinians should take a dim view of Israelis occupying what little space was left to them.

The settlers relate how, before the intifa- da erupted in December 1987, they could venture into the centre of Gaza city or even refugee camps such as Khan Younis to do their weekly shopping. But for the past six years, every time settlers have ventured outside the Gush Katif compound, they have put their lives at risk.

Even before the intifada, Yossi and Zehava Lessinger anticipated confronta- tion when they signed up for weapons training with a retired Israeli army instruc- tor. Yossi learned to use a Uzi sub- machine-gun while his wife was taught to shoot with a revolver.

The entrance to Gush Katif is only four miles from Khan Younis — scene of some of the worst intifada violence — and there have been several occasions when settlers have been surrounded by bloodthirsty crowds of Palestinians. Twice Yossi has tired his Uzi in the air to escape, while Zehava has brandished her pistol many times. The Lessingers cannot be accused of over-dramatising the threat. In the past two years eight settlers have been murdered by Palestinians. To help settlers avoid difficult areas, road signs have been constructed with no-entry signs marking potentially deadly routes. So why do they bother? Most of their compatriots in Tel Aviv would maintain that it is because they are mentally deranged. Others claim they are fanatics who refuse to countenance the idea of making peace of any sort with the Pales- tinians. In fact the presence of tfiis undoubtedly beleaguered Israeli communi- ty in Gaza goes back to the heady days after the Six Day War. There has always been something of the spirit of the fron- tiersman in the Israeli psyche, and many Israelis looked upon the lands liberated by force of arms as an opportunity for person- al advancement.

In this they were actively encouraged by Moshe Dayan, then defence minister, who had his eye firmly set on consolidating the protection of Israel's borders. Gaza, fur- thermore, was by no means the frontline of the new settlements. The more adventur- ous Israelis such as the Lessingers ven- tured into Sinai where the Israelis intended to put Nasser in his place by building a city of 100,000 people at Yamit on the Red Sea coast.

As newly-weds, Yossi and Zehava thought it too good an opportunity to miss. Yossi, whose uncle had been a professor of oriental languages at All Souls' College, Oxford, aimed to use his architectural skills to good advantage in the new city. But by 1982 the Israeli army was obliged to drag the settlers, including the Lessingers, literally kicking and screaming out of Sinai to enable Begin to honour the treaty resulting from the Camp David peace talks. Some of the Yamit houses were dis- mantled and reconstructed at Gush Katif where the Lessingers, together with many Yamit families, settled to start again.

A monument to what the settlers describe as the betrayal of Yamit has been constructed at the entrance to the main Jewish college at Gush Katif. There is no question, the Lessingers say, of a repeti- tion of Yamit at Gush Katif, no matter what opposition they face from either the Israelis or Palestinians. They have raised a family here and, after losing their home once, are not prepared to let it happen again.

Details of precisely what has been agreed between Peres and Arafat remain sketchy, though the Israeli government says the settlers are to stay put in Gaza after it receives autonomy, with limited protection from the Israeli army. But if the Palestinians are allowed to run their own affairs, the settlers believe they will, in effect, be thrown to the wolves.

The fate of the settlers in Gaza is just one .of the problems which will remain unresolved after the signing of the historic Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement. Once the first Palestinian flag is raised over the Strip, a peaceful future for Yossi and Zehava Lessinger seems unlikely.

Con Coughlin writes for the Sunday Tele- graph.

Previous page

Previous page