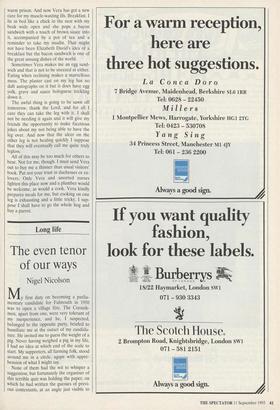

Long life

The even tenor of our ways

Nigel Nicolson

My first duty on becoming a parlia- mentary candidate for Falmouth in 1950 was to open a village fête. The Cornish- men, apart from one, were very tolerant of my inexperience, and he, I suspected, belonged to the opposite party, briefed to humiliate me at the outset of my candida- ture. He invited me to guess the weight of a pig. Never having weighed a pig in my life, I had no idea at which end of the scale to start. My supporters, all farming folk, stood around me in a circle, agape with appre- hension of what I might say.

None of them had the wit to whisper a suggestion, but fortunately the organiser of this terrible quiz was holding the paper, on which he had written the guesSes of previ- ous contestants, at an angle just visible to

my despairing eyes, and I was able to read, 56, 52, 47, 60 . . . Ibs, I supposed. I subject- ed the pig to expert scrutiny and then announced, '49'. 'My God, you've won it!' he cried. But I lost the election.

At our village fete this summer there was a contest for guessing the weight of a sheep, but I did not enter for it. All the other stalls duplicated those in Cornwall more than 40 years ago. These things are immutable. There must be a coconut shy, the ringing of a post with horseshoes, pony rides, home-made pottery, cakes and jam, the tossing of a truss of hay over a movable bar, and a competition to find the dog with the waggiest tail. The fete was opened by a retired judge, 'without more ado' (can he ever have used that dank little phrase in court?), and we walked around the field greeting our familiar neighbours in their unfamiliar roles.

It must be admitted that we are not a very handsome lot, but what we lack in looks we make up by variety of character. Since I was a boy in this same village the main changes are social. While there is undeniably a consciousness of class, it is no longer explicit. The smart ladies do not wear smart hats and the squires come tie- less. There are no labourers. The very term would be offensive, but it is not for that reason that they have disappeared. Farms no longer have need for them.

In my youth six men worked full-time on an average farm, now none. The farmer employs contract men and machinery when he needs them, and that is not often. Once he thought it his duty to make two ears of corn grow where only one grew before, but when he succeeded, he was paid to stop. So village life is infinitely more diverse. Look- ing round the fête, I could identify builders, commuters, foresters, doctors, tradesmen and the vicar. Our prosperity is modest but evident. There are no miser- able poor.

I do not mind the disappearance of the traditional countryman. We are an unsenti- mental lot. I have never heard a word of regret for the replacement of carthorses by combine harvesters nor of nostalgia that we can no longer smell at this time of year the reek of drying hops. We care deeply for our countryside and protect it against ill- sited bungalows or brick-factories. Our farmers keep their hedges trim for looks' sake when it would be more sensible and profitable to uproot them.

All this is done unostentatiously. We are not an excitable people. The village fête is the only occasion in the year when we all meet as a community, and the unadventur- ousness of it is very English. I think of the bulls rampaging through the streets of Pamplona, of the riotous celebrations that end the French vintage, of the Notting Hill carnival, of New Orleans and Oberammer- gau, and wonder why it is that in our coun- try villages we rest content with pots of home-made jam, pony rides and guessing the weight of a pig.

Previous page

Previous page