The war

Poor little bastards of Vietnam

Marina Warner

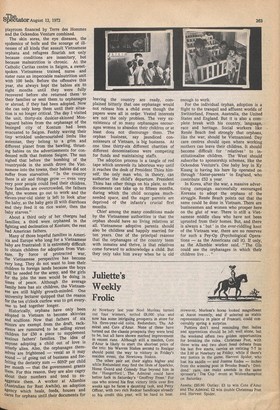

Contraceptives are available free in the PX stores of the US army, but it only needs one glance at the cots in the ramshackle orphanages of Saigon to realise that very few GIs seem to know what they are for.

In self-defence, they say, "When a man knows he's going out on a mission, that he's probably going to die, he can't plan anything." But in the streets of Saigon clean-jawed soldiers in their ironed and tailored uniforms lean over the fragile street urchins and pat them and woo them and tempt them with candy, fumbling for a relationship with these children scattered by their war efforts, who scrape a living hawking newpapers and Playboy, shining GI boots and journalists' shoes, and sleeping heaped up on doorsteps at night after curfew. And in the city's orphanages photographs of proud adoptive parents of Vietnamese babies testify to some American attempts to expiate.

During the current offensive, 700,000 old men, women and children have been swept from their homes and their living by the North Vietnamese and Vietcong attacks and by American bombing. Of these 700,000 refugees, herded now in 283 camps where they eke out an existence on government-donated rations of rice and salt, the Vietnamese Red Cross estimated that 40,000 are babies and 170,000 children between two and twelve years old. Some of these will discover, with the lapse of weeks, as their dispersed families do not reappear, that they are orphans.

There were 140,000 official orphans in Vietnam before the offensive. Such a round count did not take in the multiplying children who remain unregistered because they live off their wits in the streets, or the 400,000 children on the Ministry of War Veterans' books, whose soldierfathers have been killed to date, and whose mothers live on the war widows' monthly pittance. It did however include the children abandoned in the maternity hospitals by mothers whose economic plight makes it impossible for them to raise children and work for their bread at the same time. This practice has continued this year as always, but no Saigon orphanage reported a sudden increase during the last two months' bitter fighting.

Three days after the birth, the mother can sign a release, an tact of forsaking' to the hospital, and leave without her child. Many of these foundlings have American fathers. There is no separate reckoning for rnttis children, but workers in welfare here have estimated there must be 15,000 to 50,000 of them. (Rumours of half a million were wildly exaggerated.) Metis are by no means all forsaken. One gentle plump bar girl I met kept her little girl with her, but when a son was born, by a Navy rating, she put him in care with a friend's family for £9 a month. That was four years ago. Though she feels that Dung is still hers, she says wanly that he does not want to come and live with her now as he treats the other family as his own. Other mothers, who have parents of their own, or a trickle of money from the States, hold on to their children and will produce, proudly, albums of bright snapshots from their handbags when you offer them a drink.

There has been a great deal of alarmism about Vietnamese mothers dumping these babies because they brand them as 'collaborators.' But the Vietnamese have lived, through so many months and years of warfare and occupation the French, the Japanese, the Americans — that they are fatalist and enduring beyond western imagining and such impulsive repudiations. Also, they do not, contrary to the ravening press reports, expect a rout in South Vietnam. It is true however that in Hue during the Tet offensive in 1968 the Vietcong and North Vietnamese marked and ruthlessly proscribed westerners and all those who had truck with them. In South Vietnem, a girl on the arm of a US soldier runs a gauntlet of catcalls and heckling. Economics, prejudice, but not panic governs Vietnamese mothers. More ,metis are abandoned in ratio to their numbers than Vietnamese babies in ratio to theirs because Americans do not marry their Vietnamese girlfriends. Vietnamese fathers on the whole do. Nor are there social security benefits or family allowances for unmarried mothers in Vietnam. Nor is there birth control for women.

Outside Hoi Due Anh orphanage, where she had committed her newborn baby, a sixteen-year-old girl hovered miserably. She had no family, no work, no means of support. For her the wrench was the only intolerable alternative.

Hoi Due Anh (Society for the Nourishment of Children), founded forty-one years ago through the piety of Buddhist benefactors and therefore one of the oldest orphanages in Saigon, lies higgledy-piggledy in the centre of the city behind a row of shops and booths that sometimes donate their surplus to the children. Inside, babies doze on bare plastic with heavy stiff rags for nappies; the two-year-olds' thin bodies erupt in boils; the Vietnamese helpers squat with their belongings in corners of the flyblown courtyard or of the children's rooms, and unfortunately, but quite naturally, favour their own offspring, who live with them, with the best morsels from the daily slush of rice and fish. The threeto eight-year-olds sleep in an ill-ventilated dormitory under a communal mosquito net. Some of the children are handicapped and incontinent; the others cannot climb out of the nest without waking everyone up. Each morning one shrinks from the reek. The best room of the entire building, large, light, airy and scrupulously cleaned by the older girls, is kept locked and never used. It cannot be requisitioned. It is for prayer. Oxfam contributed to another good, airy room, and some Marines spent "surplus energy ", as their officer called it, painting over the institutional beige in places. A Vietnamese teacher, called Ko Tan, has transformed a kindergarten classroom into a marvellous panorama of painted cows and trees and flowers — her domain is like water in the Sahara.

The Ockendon Venture of Woking are also tackling the squalor. Their gentle, sensible and determined representative, Renee Beach, has already organised a group of thirteen of the worst handicapped children to go to England, together with two Vietnamese teachers, for the therapy and attention it is impossible to obtain in Saigon. Buddhism instills such defeatism about fate — karma — and nature's will, that cripples are meant to accept their condition without struggle.

Hoi Due Anh is a typical Vietnamese orphanage. It is better than some. Some money could improve it overnight, for the Ky Kuang Pagoda, where bonzesses with shaved pates and saffron robes minister gracefully to 120 children, has been transformed recently by a thorough replastering, repainting, refitting and a toy-filled playroom financed by Terre des Hommes and the Ockendon Venture combined.

The skin sores, the eye diseases, the epidemics of boils and the scourge of illnesses of all kinds that assault Vietnamese orphans and refugees flourish not only because conditions are insanitary, but because malnutrition is chronic. At the Catholic Caritas centre in Saigon, a sweetspoken Vietnamese trained nurse and sister runs an impeccable malnutrition unit with 100 beds. Before the offensive this year, she always kept the babies six to eight months until they were fully recovered before she returned them to their families or sent them, to orphanages or abroad, if they had been adopted. Now she can only keep them until their situation is no longer critical. The day I visited the unit, thirty-six duskier-skinned Montagnard babies from the orphanage of the besieged city of Kontum had been evacuated to Saigon. Feebly waving their tiny wrinkled undernourished limbs like antennae, they belong to a grim and different planet from the bawling, thrusting babies on the advertisements for condensed milk that festoon Saigon. The nun sighed that before the bombing of the countryside in the south drove the Vietnamese into the towns, their babies did not suffer from starvation. "In the country there is air and things grow — even very very poor people could feed their children. Now families are overcrowded, the fathers fight, the women go out to work and the eleven-year-old sister is left to look after the baby, so the baby gets ill with diarrhoea and they feed it on rice water, then the baby starves." About a third only of her charges had families; a third were orphaned in the fighting and decimation of Kontum; the rest had American fathers.

Many of those hopeful families in America and Europe who long for a Vietnamese baby are frustrated: it is extremely difficult to obtain children for adoption from Vietnam. By force of protracted war, the Vietnamese perspective has become very long. They do not want to lose their Children to foreign lands because the boys Will be needed for the army, and the girls for the jobs the men would be doing in times of peace. Although the average family here has six children, the Vietnamese are still highly growth-minded. One University lecturer quipped that the reason for the ten o'clock curfew was to get everyone to bed together longer. Historically, orphans have only, been adopted in Vietnam to become skivvies and scullions. Now that fathers of six minors are exempt from the draft, racketeers are rumoured to be selling street Children for £50 a piece to supplement anxious fathers' families. The idea of anyone adopting a child out of love is utterly alien. Also, the orphanages themselves are frightened — venal as it may sound — of going out of business and forfeiting the derisory sum — 60NP per child Per month — that the government grants them. For this reason, they are also cagey about their numbers and tend to exaggerate them. A worker at Allambie (Australian for Rest Awhile), an adoption agency which heals, feeds, houses and cares for orphans until their documents for leaving the country are ready, complained bitterly that one orphanage would not release him a child even though the papers were all in order. Vested interests are not the only problem. The very exexistence of so many orphanages encourages women to abandon their children or at least does not discourage them. The orphan business, say jaundiced connoisseurs of Vietnam, is big business. At one time thirty-six different charities of different denominations were competing for funds and maintaining staffs.

The adoption process is a tangle of red tape which unravels its laborious way until it reaches the desk of President Thieu himself, the only man who, in theory, can authorise the child's departure. President Thieu has other things on his plate, so the documents can take up to fifteen months, during which the child occupies muchneeded space, and the eager parents are deprived of the infants's crucial first months.

Chief among the many conditions made by the Vietnamese authorities is that the orphan should have no living relatives at all. Vietnamese adoptive parents should also be childless and happily married for ten years. One of the principal reasons that the orphanages of the country teem with inmates and thrive, is that relatives come forward to acknowledge a child. But they only take him away when he is old For the individual orphan, adoption is a flight to the tranquil and affluent worlds of Switzerland, France, Australia, the United States and England. But it is also a complete break with his country, language, race and heritage. Social workers like Renee Beach feel strongly that orphans, like the war, should be Vietnamised. Day care centres should open where working mothers can leave their children. It should become difficult for relatives ' to institutionalise children. The West should subscribe to sponsorship schemes, like the Ockendon Venture's. One baby boy in Ky Kuang is having his hare lip operated on through ' foster-parents ' in England, who contribute £52 a year.

In Korea, after the war, a massive advertising campaign successfully encouraged Koreans to adopt the orphans of the struggle. Renee Beach points out that the same could be done in Vietnam. There are businessmen and women who prosper here on the glut of war. There is still a Vietnamese middle class who have not been uprooted from their homes. But, and there is always a 'but' in the ever-riddling knot of the Vietnam war, there are no reserves for such a Pay-Op (Psychological Operations — as the Americans call it). If only, as the Allambie worker said, "The GIs could see the orphanages in which their children live ... "

Previous page

Previous page