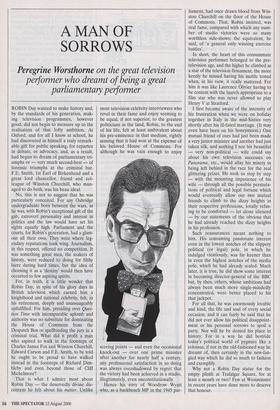

A MAN OF SORROWS

performer who dreamt of being a great parliamentary performer

ROBIN Day wanted to make history and, by the standards of his generation, mak- ing television programmes, however good, did not begin to measure up to the realisation of that lofty ambition. At Oxford, and for all I know at school, he had discovered in himself a truly remark- able gift for public speaking, for repartee in debate, or advocacy, and, as a result, had begun to dream of parliamentary tri- umphs or — very much second-best — of forensic triumphs at the criminal bar. F.E. Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead and a great lord chancellor, friend and col- league of Winston Churchill, who man- aged to do both, was his beau ideal.

No, this is not to suggest that he was particularly conceited. For any Oxbridge undergraduate born between the wars, as he was, with Robin's exceptional gift of the gab, extrovert personality and interest in politics and the law would have set his sights equally high. Parliament and the courts, for Robin's generation, had a glam- our all their own. They were where leg- endary reputations took wing. Journalism, in this respect, offered no competition. It was something great men, the makers of history, were reduced to doing for filthy lucre during hard times, but the idea of choosing it as a 'destiny' would then have occurred to few aspiring spirits.

For, in truth, it is little wonder that Robin Day, in spite of his glory days in British television which earned him a knighthood and national celebrity, felt, in his retirement, deeply and unassuageably unfulfilled. For him, presiding over Ques- tion Time with incomparable aplomb and authority was no substitute for dominating the House of Commons from the Despatch Box or spellbinding the jury in a criminal trial. What did it profit a man who aspired to walk in the footsteps of Charles James Fox and Winston Churchill, Edward Carson and F.E. Smith, to be told he ought to be proud to have walked instead in the footsteps of Richard Dim- bleby and even beyond those of Cliff Michelmore?

That is what I admire most about Robin Day — the deservedly divine dis- content he felt about his metier. Unlike most television celebrity interviewers who revel in their fame and enjoy seeming to be equal, if not superior, to the greatest politicians in the land, Robin, to the end of his life, felt at least ambivalent about his pre-eminence in that medium, rightly sensing that it had won at the expense of his beloved House of Commons. For although he was vain enough to enjoy scoring points — and even the occasional knock-out — over one prime minister after another for nearly half a century, any professional satisfaction in so doing was always overshadowed by regret that the victory had been achieved in a studio, illegitimately, even unconstitutionally.

Hence his envy of Woodrow Wyatt who, as a backbench MP in the 1945 par- liament, had once drawn blood from Win- ston Churchill on the floor of the House of Commons. That, Robin insisted, was real fame, compared with which any num- ber of studio victories were so many worthless side-shows; the equivalent, he said, of 'a general only winning exercise battles'.

In short, the heart of this consummate television performer belonged to the pre- television age, and the higher he climbed as a star of the television firmament, the more keenly he missed having his mettle tested when, in his view, it really mattered. For him it was like Laurence Olivier having to be content with the laurels appropriate to a film star who was never allowed to play Henry V at Stratford.

I first became aware of the intensity of his frustration when we were on holiday together in Italy in the mid-Sixties very shortly after his ill-fated marriage. (It may even have been on his honeymoon.) One mutual friend of ours had just been made a very junior minister and another had just taken silk, and nothing I nor his beautiful — very non-political — wife could say about his own television successes on Panorama, etc., would allay his misery in being left behind in the race for the real glittering prizes. He took us step by step — with the mounting impatience of his wife — through all the possible permuta- tions of political and legal fortune which would eventually allow our two mutual friends to climb to the dizzy heights in their respective professions, totally refus- ing to be comforted — let alone silenced — by our statements of the obvious that he had already reached the dizzy heights in his profession.

Such reassurances meant nothing to him. His consuming passionate interest even in the lowest notches of the slippery political (or legal) pole, in which he indulged vicariously, was far keener than in even the highest notches of the media pole, which he had already scaled. Much later, it is true, he did show some interest in becoming director-general of the BBC but, by then, others, whose ambitions had always been much more single-mindedly concentrated, were better placed to hit that jackpot.

For all that, he was enormously lovable and kind, the life and soul of every social occasion, and it can fairly be said that he did not ever allow his political disappoint- ment or his personal sorrows to spoil a party. Nor will he be denied his place in history. For in a way he did bestride today's political world of pygmies like a colossus, if not in the old-fashioned way he dreamt of, then certainly in the new-fan- gled way which he did so much to fashion and exemplify.

Why not a Robin Day statue for the empty plinth at Trafalgar Square, for at least a month or two? Few at Westminster in recent years have done more to deserve that honour.

Previous page

Previous page