The goodness of Guinness

Mark Steyn remembers Sir Alec, who died late last week Aec Guinness was an occasional con- tributor to The Spectator and a regular reader of it, though for some years I was never certain whether he got as far as the film column. His friend Graham Greene had been our motion picture critic and he may have felt, quite reasonably, that the Speccie's movie heyday was long past. But four years ago I was reviewing the Gwyneth Paltrow version of Emma and, prodded by the alleged Jane Austen expert I made the mistake of taking along to the screening, I bemoaned the ghastly dialogue, full of 'ostentatious non-Austenisms like "Good God!"' A letter from Sir Alec arrived a few days later, citing chapter and verse on the use of 'Good God!' in the original novel.

I'm not sure what surprised me most — the fact that, at 82, Alec Guinness could be bothered reading a review of a Gwyneth Paltrow flick, or the fact that he knew his Jane Austen that well. It certainly wasn't for professional reasons. Unlike the other theatrical knights with whom he was linked, he wasn't a period guy. He was the Fool to Olivier's Lear in 1946 and Richard III in the very first of Canada's annual Stratford Festivals in 1953, but film seemed to make him wary of Shakespeare and, when he finally got to Lear, it was on radio: he may have been 'the man of a thousand faces', but the rest of him operated more cau- tiously and on the whole eschewed doublet and hose.

His two great period roles, in their dif- ferent ways, are Charles I in Cromwell and Obi-Wan Kenobi in Star Wars. The consen- sus is that, unlike most movie actors, GuM- ness never played 'himself. But who else is Obi-Wan? The quiet authority, the dignity, the spiritual strength of the character come from Guinness, not from George Lucas and what the actor called the 'second-hand, childish banalities' of the dialogue.

Incidentally, for a classic Guinness per- formance, look up any old talk-show or interview where he's asked if it's true he gets 2J/4 per cent of Star Wars plus addition- al points from the videos, sequels, etc. There's a beatific smile he nailed down early on, as he replies that, my word, yes, apparently, he does, Lots of British actors despise movie work, not least their own, but Guinness pulled off a deal that must have made him one of the wealthiest of English thespians: according to some accounts, he made over £150 million from Star Wars. That's a long way from his Eal- ing salaries, though even then he impressed his colleagues. Meeting Edith Evans at a swank restaurant, he told her not to worry, lunch was on him. He was making The Lavender Hill Mob, and they were paying him £6,000. Dame Edith went into full handbag mode. `£6,000!' she gasped. 'I must make another film. Or do you call them movies?'

Guinness could have used the Star Wars dough to make his own great British film, but that wasn't his style: insofar as one can determine, his last professional engage- ment was a voiceover for, sportingly enough, an Inland Revenue public service announcement. The points-deal was worth it to Lucas: he wanted Star Wars to be mythic, and Guinness obliges; without him, it would be just a poor man's Star Trek — lame actors prancing around in crimplene jumpsuits like a Seventies TV dance troupe.

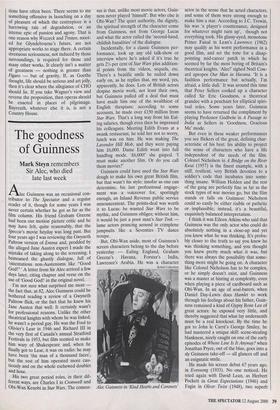

But, Obi-Wan aside, most of Guinness's screen characters belong to the day before yesterday — Ealing England, Graham Greene's Havana, Forster's India, Lawrence's Arabia. He was a character Alec Guinness in 'Kind Hearts and Coronets' actor in the sense that he acted characters, and some of them were strong enough to make him a star. According to J.C. Trewin, his was 'a player's countenance, designed for whatever might turn up', though not everything took. His glassy-eyed, monotone Prince Faisal in Lean's Lawrence (1962) may qualify as his worst performance in a good film, and set the tone for a disap- pointing mid-career patch in which he seemed by far the most boring of Britain's theatrical knights. 'Alec!' sighed Noel Cow- ard apropos Our Man in Havana. 'It is a faultless performance but actually, I'm afraid, a little dull.' It was around this time that Peter Sellers cooked up a character called Sir Eric Goodness, a theatrical grandee with a penchant for elliptical spiri- tual roles. Some years later, Guinness seems to have returned the compliment by playing Professor Godbole in A Passage to India as Sellers in 'Goodness, Gracious Me' mode.

But even in these weaker performances you see flickers of the great, defining char- acteristic of his best: his ability to project the sense of characters who have a life independent of the needs of the film. Colonel Nicholson in A Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) is the finest example, with a stiff, resilient, very British devotion to a soldier's code that incubates into some- thing insane. William Holden and the rest of the gang are perfectly fine as far as the stock types of war movies go, but the film stands or falls on Guinness: Nicholson could so easily be either risible or pathetic or implausible; instead, it's a beautiful, exquisitely balanced interpretation.

I think it was Eileen Atkins who said that Guinness was the only actor who could do absolutely nothing in a close-up and yet you knew what he was thinking. It's proba- bly closer to the truth to say you knew he was thinking something, and you thought you knew pretty much what it was, but there was always the possibility that some- thing more might be going on. A character like Colonel Nicholson has to be complex, or he simply doesn't exist, and Guinness was a master at hinting at complexity, even when playing a piece of cardboard such as Obi-Wan. In an age of soul-barers, when Daniel Day-Lewis does Hamlet to work through his feelings about his father, GuM- ness remained a kind of Gypsy Rose Lee of great actors: he exposed very little, and thereby suggested that what lay underneath must be a real knockout. By the time he got to John le Carre's George Smiley, he had mastered a unique skill: scene-stealing blankness, nicely caught on one of the early episodes of Whose Line Is It Anyway? when Jonathan Pryce, out of the blue, goes into a sly Guinness take-off — all glances off and an enigmatic smile.

He made his screen debut 67 years ago, in Evensong (1933). No one noticed. He tried again with David Lean, as Herbert Pockett in Great Expectations (1946) and Fagin in Oliver Twist (1948), two superb performances. Then came his finest group of pictures — the Ealing years, beginning with Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), in which he played eight different members of the d'Ascoyne family bumped off, in suc- cession, by Dennis Price. Poor old Price actually gives the best performance, but no one cares: Kind Hearts is a novelty turn for Guinness, but the film has a harder edge than his other Ealing films. To contempo- rary movie-goers, British and American, Ealing is a far more remote world than any in Star Wars — the films are hard to get hold of and rarely shown on TV — but they show off brilliantly a youngish actor of unpromising looks but boundless inventive- ness. He had, by all accounts, a lower regard for his art than the other theatrical knights, but it served him well. And, unlike Olivier or Gielgud, Alec Guinness pulled off a unique double: he remains the only man in the galaxy to be knighted both by Her Majesty The Queen and the Jedi.

Previous page

Previous page