ARTS

Aseason which was meant to cele- brate LCDT's 21st anniversary turned out to be more of a knell for a company heading for the rocks. Towards the end of the third and final week there was only a smattering of people at the Wells — many presumably scared off by the direness of the opening programme, The Phantasma- goria. Brazenly commercial, this promotes itself as a modern version of the magic lantern shows of the 1790s, with mythical characters, special effects and showbiz dancing, but its creators badly misjudged the level of junk fodder that even Joe Public will swallow.

Except for a mildly amusing solo built round a trick smoking-jacket (by Darshan Singh Bhuller for Kenneth Tharp), the first half is the work of Robert Cohan, the company's director, who has a lot to answer for this season. Feeble ideas and schoolboyish jokes make Michael Clark's more juvenile efforts seem masterpieces of wit and theatricality; while the one promis- ing section, featuring dancers clad in Bridget Riley stripes camouflaged against an identical background, has its impact diminished by the perfunctoriness of Cohan's choreography.

Part two is mostly given over to dancing, arranged by Tom Jobe, renowned for his popular touch, but who on this occasion dishes up half a dozen routines so banal they would not even make a cabaret floor on a Sealink ferry. Semi-disco, semi-Come Dancing — and under-rehearsed at that the numbers are divided into sections dedicated to Patsy Cline, Piaf, Callas and three miscellaneous men. 'Probably Aids victims,' I heard someone venture at the interval. It was the most depressing even- ing I've spent in years.

Robert North's Fabrications, which be- gan the second programme, was only marginally better. 'Inspired' by an assort- ment of Elizabeth Emanuel's costume de- signs, the choreography is correspondingly disjunctive — lurching from Kabuki slap- stick to wild-animal imitations — and hopelessly lacking in movement ideas. As if responding to the paucity of material, the dancers looked flaccidly unplaced, and yet this is a company known for its strength and clarity.

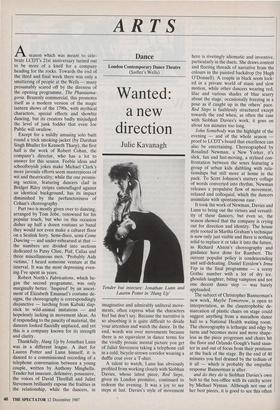

Thankfully, Hang Up by Jonathan Lunn was in a different league. A duet for Lauren Potter and Lunn himself, it is danced to a commissioned recording of a telephone conversation between a young couple, written by Anthony Minghella. Tender but insecure, defensive, possessive, the voices of David Threlfall and Juliet Stevenson brilliantly expose the frailties in the relationship, while the dancers, in

Dance

London Contemporary Dance Theatre (Sadler's Wells)

Wanted: a new direction

Julie Kavanagh Tender but insecure: Jonathan Lunn and Lauren Potter in 'Hang Up' imaginative and admirably unliteral move- ments, often express what the characters feel but don't say. Because the narrative is so absorbing it is quite difficult to divide your attention and watch the dance. In the end, words win over movements because there is no equivalent in dance terms for the vividly prosaic mental picture you get of Juliet Stevenson taking a telephone call in a cold, bicycle-strewn corridor wearing a duffle coat over a T-shirt.

A talent to watch, Lunn has obviously profited from working closely with Siobhan Davies, whose latest piece, Red Steps, given its London premiere, continued to redeem the evening. It was a joy to see steps at last. Davies's style of movement here is rivetingly idiomatic and inventive, particularly in the duets. She draws content and fleeting threads of narrative from the colours in the painted backdrop (by Hugh O'Donnell). A couple in black seem lock- ed in a private world of stasis and slow motion, while other dancers wearing red, lilac and various shades of blue scurry about the stage, occasionally freezing in a pose as if caught up in the others' pace. Red Steps is faultlessly structured except towards the end when, as often the case with Siobhan Davies's work, it goes on about ten minutes too long.

John Somebody was the highlight of the evening — and of the whole season proof to LCDT's board that excellence can also be entertaining. Choreographed by Rosalind Newman, a New Yorker, it's slick, fun and fast-moving, a stylised con- frontation between the sexes featuring a group of urban kids dabbling with rela- tionships but still more at home in the pack. To Scott Johnson's stuttery collage of words converted into rhythm, Newman releases a propulsive flow of movement, relaxed and colloquial, which the dancers assimilate with spontaneous ease.

It took the work of Newman, Davies and Lunn to bring out the virtues and versatil- ity of these dancers, but even so, the season showed that the company is crying out for direction and identity. The house style rooted in Martha Graham's technique is now only just visible and there is nothing solid to replace it or take it into the future, as Richard Alston's choreography and guidance have done for Rambert. The current populist policy is condescending and self-defeating. Daniel Ezralow's Irma Vep in the final programme — a corny Gothic number with a lot of dry ice, ghoulish laughter, biting vampires and not one decent dance step — was barely applauded.

The subject of Christopher Bannerman's new work, Maybe Tomorrow, is open to interpretation, as the claustrophobic de- marcation of plastic chairs on stage could suggest anything from a marathon dance hall to a National Health waiting room. The choreography is lethargic and edgy by turns and becomes more and more shape- less as the piece progresses and chairs hit the floor and Orlando Gough's band saun- ter in and out of focus from their positions at the back of the stage. By the end of 40 minutes you feel drained by the tedium of it all — which is probably the empathic response Bannerman is after.

and do they do is Siobhan Davies's own bob to the box-office with its catchy score by Michael Nyman. Although not one of her best pieces, it is good to see this often solemn, introverted choreographer loosen up and work at speed. And in the context of the programme, it did at least provide a ray of hope.

Previous page

Previous page