Exhibitions

Edward Burra (Lefevre, till 18 December) James Cowie (Bourne Fine Art, till 18 December) Eric Robertson (Piccadilly Gallery, till 24 December)

Putting on the style

Giles Auty

In most Western countries emphasis on style has become more and more central to the culture. Today entire industries depend on the transience of style to activate the buying habits of millions. Even the most thoughtful, anti-consumerist conservatives among us could be held to project their own distinctive, low-key 'style', while at the other extreme youthful obsessions with appearance, mannerism, vocabulary and mode of transport create for many their sole, ersatz illusion of individuality. Little observation is required to note that the dimmer and more monosyllabic the expo- nent, the more extreme the modes of dress and behaviour. Yet surely punks, skin- heads et al are simply other manifestations of the insecure conformist? The genuine radical in such a peer group would have little choice now but to dress and behave conservatively.

Inevitably the current youthful obsession with the superficialities of 'street' style has moved up a cultural notch to infest the world of contemporary art. Speaking with a group of young would-be art critics the other day, it was clear that style is now the major means of identification and reassur- ance between aspirant members. The style currently in favour is based on crude, uncouth drawing allied to arbitrary or meaningless symbolism. The illusion given is one of anarchy and excitement and is intended to convey — if anything — the errors committed by 'the establishment' in dealing with more or less every facet of life on this planet. In short, what could any responsible young artist do other than feel outraged and alienated?

Writing of the Turner Prize last week, I ventured to suggest that generous sponsors should now cast their nets rather wider if seeking to encourage the new and genuine- ly significant. Artists who have merely shown some aptitude for picking up the superficialities of current international styles have no legitimate claim to the latter description. I find it hard to understand why responsible critics and other adjudica- tors show themselves so consistently gulli- ble in their involvement with the latest modes. The creation of significant style has to be a personal, rather than an interna- tional process. The artist cannot help being original, in the only sense in which such a description has value, if pursuing his or her personal interests.

Britain has an enviable record of produc- ing idiosyncratic artists and I would recom- mend young artists to make these, rather than the merely fashionable, their guides. Not to ape their styles, of course, but to examine the reasons for their singularity; lengthy study of a straightforward land- scape by Edward Burra is necessary before one understands the reasons for its extraor- dinary charge.

Exhibitions of work by Edward Burra (1905-1976) are all the more welcome for their rarity. The Lefevre Gallery (30 Bru- ton Street, W1) is currently showing 21 important works, some of which will be unfamiliar to many viewers. I feel Burra's odd, impish genius shines through most strongly when it is least self-conscious. `The Alley, Ireland' and 'In the Lake District No. 1' please me particularly for such reasons. The former makes use of an extraordinary composition to give a haunt- ing evocation of place and time. Burra's landscapes are still critically undervalued, perhaps because full of subtle nuances which the style-obsessed ignore. James Cowie (1886-1956) at Bourne Fine Art (14 Mason's Yard, Duke Street, SW1) is another example of the true individualist. His work relates faintly, if unconsciously, to Neue Sachlichkeit — the `new objectivity' of artists such as Christian Schad in Germany — and to the glassy realism of Meredith Frampton in England, yet is markedly kinder in spirit than the first and less frigid than the latter. Fifty- five small drawings and paintings show the versatility and artistic bite of this sensitive Scottish realist. Exquisite pencil drawings have a restrained elegance that is curiously self-effacing. Cowie, like other good artists, formulated a style for himself which was inextricably bound up with what he alone wanted to say. Style or formal innovation conceived for reasons other than personal expression have the ill-fitting appearance of borrowed clothes.

Lovers of true pictorial subtlety will find much to enjoy in works such as 'Corn- stooks, Hospitalfield' and 'Appledore I'. In the latter, a flight of steps leads the eye, via a brightly coloured arch and tall chim- ney, to the distant shore of the estuary. No sky is seen but we understand exactly what sort of day it was when the artist brought his knowledge and skill to bear on record- ing a few moments in the ,life of a small North Devon town. The artist's sense of construction shines through similarly in `Still Life with Four Shells' and 'Portrait of

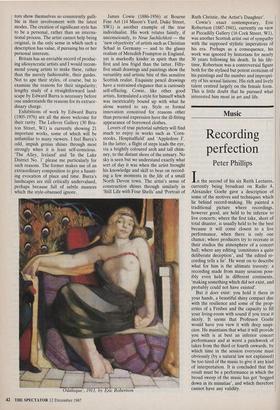

'Odalisque', 1913, by Eric Robertson

Ruth Christie, the Artist's Daughter'.

Cowie's exact contemporary, Eric Robertson (1887-1941), currently on view at Piccadilly Gallery (16 Cork Street, WO, was another Scottish artist out of sympathy with the supposed stylistic imperatives of his era. Perhaps as a consequence, his work was ignored by historians for nearly 30 years following his death. In his life- time, Robertson was a controversial figure both for the stylised but potent eroticism of his paintings and the number and impropri- ety of his sexual liaisons. His rich and lively talent centred largely on the female form. This is little doubt that he pursued what interested him most in art and life.

Previous page

Previous page