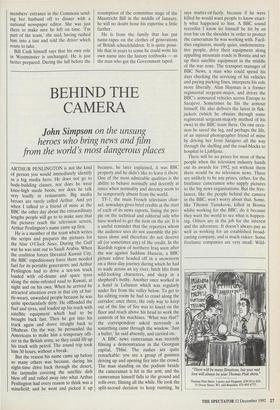

BEHIND THE CAMERA

John Simpson on the unsung heroes who bring news and film from the world's most dangerous places

ARTHUR PENLINGTON is not the kind of person you would immediately identify as a big media hero. He does not go to body-building classes, nor does he wear knee-high suede boots, nor does he talk very loudly in restaurants. Big media heroes are rarely called Arthur. And yet when I talked to a friend of mine at the BBC the other day about the extraordinary lengths people will go to to make sure that the pictures reach the television screen, Arthur Penlington's name came up first.

He is a member of the team which writes the scripts and prepares the pictures for the Nine O'Clock News. During the Gulf war he was sent out to Saudi Arabia. When the coalition forces liberated Kuwait City, the BBC expeditionary force there needed fuel for its portable generators; and Arthur Penlington had to drive a ten-ton truck loaded with oil-drums and spare tyres along the mine-infested road to Kuwait, at night and on his own. When he arrived he attracted attention even in that city of bat- tle-weary, unwashed people because he was quite spectacularly dirty. He offloaded the fuel and tyres, and loaded up his truck with satellite equipment which had to be brought back fast. Then he got into his truck again and drove straight back to Dhahran. On the way, he persuaded the Americans to make him a temporary offi- cer in the British army, so they could fill up his truck with petrol. The round trip took him 30 hours, without a break.

But the reason his name came up before so many others was because, during his night-time drive back through the desert, the tarpaulin covering the satellite dish blew off and rolled away into what Arthur Penlington had every reason to think was a minefield; and he went and picked it up because, he later explained, it was BBC property and he didn't like to leave it there. One of the most admirable qualities is the ability to behave normally and decently at times when normality and decency seem to be temporarily absent from the world.

TF-1, the main French television chan- nel, nowadays gives brief credits at the start of each of its news reports, listing the peo- ple on the technical and editorial side who have worked to get the item on the air. It is a useful reminder that the reporters whom the audience sees do not assemble the pic- tures alone and therefore do not deserve all (or sometimes any) of the credit. In the Kurdish region of northern Iraq soon after the war against Saddam Hussein, a BBC picture editor headed off in a snowstorm on a three-day journey during which he had to wade across an icy river, hitch lifts from wild-looking characters, and sleep in a shepherd's bothy. Another once worked in a hotel in Lebanon which was regularly under fire from the valley below. To get to his editing room he had to crawl along the corridor; once there, the only way to keep out of the line of fire was to kneel on the floor and reach above his head to work the controls of his machines. 'What was that?' the correspondent asked nervously as something came through the window. 'Just a bullet,' he said absently, and carried on.

A BBC news cameraman was recently filming a demonstration in the Georgian capital, Tblisi. The rushes are quite remarkable: you see a group of gunmen driving up and opening fire into the crowd. The man standing on the podium beside the cameraman is hit in the arm, and the cameraman himself falls to the ground and rolls over, filming all the while. He took the split-second decision to keep running, he says matter-of-factly, because if he were killed he would want people to know exact- ly what happened to him. A BBC sound recordist I know let himself be hit by an iron bar on the shoulder in order to protect the cameraman he was working with. Facil- ities engineers, mostly quiet, undemonstra- tive people, drive their equipment along appalling mountain roads in Bosnia and set up their satellite equipment in the middle of the war zone. The transport manager of BBC News, a man who could spend his days checking the servicing of his vehicles and paying parking fines, interprets his role more liberally. Alan Hayman is a former regimental sergeant-major, and drives the BBC's armoured vehicles across Europe to Sarajevo. Sometimes he fits the armour himself. He also delivers the latest in flak- jackets (which he obtains through some regimental sergeant-majorly method of his own) to the BBC team there. On one occa- sion he saved the leg, and perhaps the life, of an injured photographer friend of mine by driving her from Sarajevo all the way through the shelling and the road-blocks to hospital in Ljubljana.

There will be no prizes for most of these people when the television industry hands out its awards for 1992, yet without them there would be no television news. There are unlikely to be any prizes, either, for the freelance cameramen who supply pictures to the big news organisations. But the free- lances, like the people behind the camera in the BBC, won't worry about that. Some, like Tihomir Tunukovic, killed in Bosnia whilst working for the BBC, do it because they want the world to see what is happen- ing. Others are in the job for the interest and the adventure. It doesn't always pay as well as working for an established broad- casting company, and is much riskier. Some freelance companies are very small: Wild- cat, for instance, which consists simply of a cameraman and a producer/reporter. Newsforce, by contrast, which is based in Cyprus and staffed mostly by Australians, is the size of a small television station and sends its crews and picture editors any- where. Australian and British cameramen are generally regarded as the best at war coverage.

The biggest and most successful of the British freelance companies is Frontline. Frontline is essentially an agency for cam- eramen and women; it is organised by a small core of full-time shareholders, who market their own work and that of other freelances. Much of it goes to Germany and Japan — it helps that one of the shareholders speaks good Japanese — and the best appears on British television. Frontline has stopped accepting the tradi- tional freelance offerings of shaky, hand- held combat footage which trombones in and out of the action like an amateur video — what is known in the trade as Wobblevision'. Instead, it will use only well-shot, properly crafted reports.

Frontline began with a small group of self-taught, ex-army people, most of them from 'good' regiments, who wanted some- thing more exciting than a new career in the City. They gravitated to Peshawar, on the north-west frontier of Pakistan, and began to cover the war in Afghanistan. Many crooks and charlatans were doing the same thing, and some dubious footage worked its way onto American television in particular. Pictures of what seemed to be spectacular mujaheddin successes against Soviet troops were really filmed in Pak- istan. Once an American network showed a bombing raid by Soviet aircraft — only the aircraft in question were clearly Pak- istani, and the bomb explosions were cut in from other footage.

The British group in Peshawar was very different. Men like Peter Jouvenal, Rory Peck and Ken Guest competed with each other to get the best pictures of action between the Russians and the mujaheddin, and their work carried its own guarantee: none of them would be associated with anything that was questionable. Peter Jou- venal — formerly of the Royal Horse Artillery — was the central figure of the group, and no one made more trips into Afghanistan than he did. Bearded and wearing Afghan dress, he looked like some 19th-century player of the Great Game.

He and I managed to get into Kabul together immediately after the Soviet withdrawal. Guided by a Shi'ite mujahed- din group, we drove through the city in the jeep belonging to the chief of the secret police, which the mujaheddin had pro- cured for us to demonstrate their influ- ence. We left two days later, just ahead of the secret police who had found out where we were. I looked round at Peter as he sat ramrod-straight in the taxi we were escap- ing in and hissed, 'Can't you stop looking so much like a bloody British officer?' He slouched down in his seat, but it didn't help. His speech is famously clipped. On our way back from Kabul, he had been driving for two days and nights when we found ourselves stuck in thick snow on a narrow mountain road with a line of bro- ken trucks on one side and a precipice on the other. 'What's the worst that could happen?' I asked, nervous that we might have to spend the night there. 'We could always go over the edge,' he said, briskly. He and the cameraman Vaughan Smith, a former Guards officer who used his old army background to talk his way into Saudi Arabia during the Gulf war and obtained the best and most spectacular television pictures of the ground fighting, now help to run Frontline. Its success lies in its ability to combine the freelance instinct with professional discipline. But these are people who do not feel comfort- able working for a big organisation. Tira Shubart, with whom I live, is another

A 0 /3 E R7 TN0 /`••■PSO'v • 'I suppose it's just one of those things.' Frontline member. She worked with me as a producer in Bucharest during the Ruma- nian revolution; at one stage, in order to get our report to the television station for satelliting to the BBC in London, she had to run 200 yards through a field with sol- diers and Securitate snipers firing at each other across it. She got there, and the report was broadcast. Afterwards, no one thanked her for it except me, and when the awards came round, her name wasn't men- tioned. For the people behind the camera, doing the job properly has to be its own reward.

John Simpson is Foreign Affairs Editor of the BBC.

Previous page

Previous page