2 - Beer and Scuffles From GRACE SCOTT A TIME-HONOURED South African

custom, which has spread to the Rhodesias, is for town councils and management boards with large African populations in their responsibility to sell beer to them and to use the profits for financing welfare schemes, sports facilities and other amenities. And lately there has 'peen a ten- dency for some town councils to use a portion of such profits on essential services as well. One or dency for some town councils to use a portion of such profits on essential services as well. One or two—Salisbury Municipality, for instance, which has as much as £200,000 in accumulated beer pro- fits—refuse to do this on moral grounds; but in some of the smaller, less affluent municipalities such inhibitions are often thrown overboard, to meet commitments to their ever-increasing urban African populations. With no means of collecting rates from Africans as yet, they are faced with the formidable problem of providing water sup- plies, drainage, roads, maintenance and admini- strative staffs and other essentials out of a deficit on house rentals. Small wonder they are tempted to turn to their easies1 and most lucrative source of income—beer.

Children's playgrounds, football pitches, youth clubs, entertainment halls and cemeteries for Africans are all dependent upon the amount of beer Africans can be persuaded to drink. They cannot hope to better their social lot unless they drink it in sufficient quantities. And Government or municipal officials, however upright, high- principled and abstemious, if questioned on the ethics of such a system, say that the African must have his beer; not only is it his national drink, but it is a most valuable form of food, and has impor- tant medicinal properties as well.

Kaffir beer, as it is more frequently called, is brewed from the grain of maize, millet or kaffir corn, whichever is the main crop of the district.

It takes from two to five days to mature, turns sour very quickly and cannot be stored for more than two or three days, so that a quick turnover is an economic necessity. Its alcoholic content is roughly 3 per cent. to 4 per cent, and it is sold in the beerhalls for 7d. a quart.

In an American TV programme about Central Africa last year, the narrator described kaffir beer as served in municipal beerhalls as being 'made with the odour, texture and warm soapiness of pig swill, and so served.' To the average white man the brew, which still retains much of its sedi- ment (or 'porridge' as Africans call it), might well look more fit for swine than for human consump- tion, especially served as it is in the beerhalls in rough, handleless tins. But Africans themselves have great faith in the food value of their beer and sometimes prove their point by subsisting on it for several days on end. The fact that during this time they lose all desire for solid food is to them indicative of its virtue.

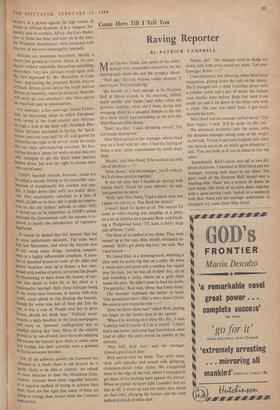

It is worth while comparing the vital statistics of kaffir beer with those of milk, since the value of milk as a food is universally recognised.* Even without very close scrutiny, the Egures explode the kaffir beer myth. Its medicinal quali- ties are small and most of the nourishment that City Fathers like to imagine they are selling to African imbibers is probably removed in the resi- due which is usually sold to pig farmers. Their stock, according to reports, waxes extremely fat on the diet.

Municipal beerhalls, or beer gardens as some prefer to call them, are usually neither halls nor gardens and vary in style and comfort according to the wealth of the location; but they continue to provide fun and relaxation for thousands. A beerhall is usually an enclosure with a few benches, a small 'bar' to house and serve the beer, and two or three latrines. Customers stand, walk around or sit on the ground in convivial groups. A band may add gaiety to the proceedings. In the Lusaka beerhalls a large hangar-like structure is being erected in one corner (on the proceeds from the 1958 profits) and this, when it is completed, should pay dividends in the wet season by pro- viding shelter for the hundreds of patrons who might otherwise be deterred by the rains.

Unhappily, however justified the City Fathers feel in improving beerhall facilities, however fine a food they insist kaffir beer is, and however many excellent benefits are derived from its profits, it can still be the African's worst enemy. One Northern Rhodesia Judge said in court recently that 85 per cent. of African murders were committed as a result of overindulgence in beer. Police would probably estimate the general crime percentage at an even higher figure. Hos- pital staffs would testify that their busiest time in African hospitals is at week-ends when they are called upon at all hours to patch up the damage wrought by knives, axes, clubs, fists and teeth in the course of brawls which tend to start over the tins of kaffir beer. Any motorist in the country knows that to drive in the vicinity of the loca- tions after beerhall closing time is a hazardous business. The streets are full of reeling, shouting, drunken Africans—some on bicycles, some under them, some on their feet weaving crazily from one side of the road to the other, some being dragged along by willing if unsteady friends, oblivious of passing traffic (unless they are in a truculent mood and are aiming stones at it). Many a so-called political incident has proved to be little more than an alcoholic show of bravado on the part of a few disgruntled Africans. Kaffir-beer enthusiasts can say what they like about its medicinal or nutritive qualities; it can convert a reasonable African into a sodden sub-human.

Kaffir beer recently became an issue here when the United National Independence Party (UNIP) staged a boycott of municipal beerhalls in the

KAFFIR BEER *MILK (Rhodesian Variety) (per ounce) ( per ounce)

Protein 0.9 grammes 0.2 grammes Carbohydrates 1.2 grammes 0.7 grammes Fat 1.0 grammes nil Vit. A 30 int. units nil Vit. B, 4 int. units approx. 1 int. unit Vit. C 0.3 mgms. 0.2 mgms.

Riboflavin 0.04 mgms. 0.007 mgms.

Nicotinic Acid Trace 0.14 Calories 17 5-15 (depend- ing on amount of 'porridge' left in beer). territory as a protest against the high rentals of houses in African locations. It is a 'weapon' fre- quently used in southern Africa; the Cato Manor riots in Natal last June and later on in the year, the Windhoek disturbances, were connected with boycotts of the local municipality beerhalls.

Africans are inveterate boycotters. Hardly a season has passed in Central Africa in the past decade without somebody boycotting something, somewhere. Very few Africans would agree with the view expressed by Mr. Macmillan in Cape Town, deprecating the proposed British boycott of South African goods before the South African Houses of Assembly, when he declared, 'Boycotts will. never get you anywhere'; they have played an important part in emancipation.

For example : a few years ago, before Federa- tion, by boycotting shops in which Europeans were served at the front counter and Africans through a hole in the back wall, Northern Rho- desian Africans succeeded in having the 'hatch' System removed once and for all, and gained for themselves 'the right to be served inside the shops like any other self-respecting customer. By boy- eattiog butchers' shops for weeks on end they not Only managed to get the blackf white barriers broken down, but won the right to choose their OW n cuts of meat.

UNIP's beerhall boycott, however, could not be called a success. Owing to the irresistible com- bination of exceptionally hot weather and pay- day, it broke down after only two weeks' dura- tion. One Municipality admitted to a loss of nearly £2,000 on its beer, but it made no impres- Slon on the city fathers' attitude to rents. Still, It turned out to be important, as UNIP's action Provided the Government with the excuses it re- quired to justify the introduction of repressive legislation.

It cannot be denied that this boycott had led to some unfortunate incidents. The rains were late last November, and when the boycott was In full swing many things, including tempers, were in a highly inflammable condition. A num- ber of thatched houses in some of the older and Poorer locations went up in flames; a few men, armed with bottles of petrol, terrorised the people by threatening to burn down the houses of any- 00e who dared to slake his or her thirst at a u.lunicipality beerhall. Only those Africans living In the better-class locations, in houses with iron roofs, could afford to risk flouting the boycott, though for some time few of them did. For the rest, it was a case of 'People who live in grass houses should not drink beer.' Political arson' became a daily headline in the local newspapers and many an 'innocent' conflagration was so labelled during that time. Most of the culprits Proved to be out-of-work ne'er-do-wells enjoying the excuse the boycott gave them to make some real trouble, but their activities were a godsend to the Government benches.

For all the arbitrary powers the Governor has Obtained as a result, there is one boycott he is hardly likely to be able to control: the refusal Of most Africans to meet the Monckton Com- Mission. Africans have never regarded boycotts as a negative method of trying to achieve their ends; there are few signs that many of them are g.°Ing to change their tactics when the Commis- sion arrives.

Previous page

Previous page