A very mixed-up mole

Nicholas von Hoffman

Washington

Englishmen betray their country for sex and/or love; Americans do it for money. But did Michael Straight, the Anglo-American, betray his, or what did he do, or not do, that he should have done, or not done? Straight, whose brother Whitney was the chairman of Rolls-Royce, has published a book here, more of a memoir than an autobiography, telling his part in the Blunt, Burgess et a/ spy ring (After Long Silence by Michael Straight, W.W. Norton and Co, New York, 1983). It is the unfocused confession of a wealthy young man who was part of, but not party to — he says — the homosexual communism of Cambridge University in the 1930s. It is a confused tale of a deracinated, disoriented, discombobulated man who was too weak to say yes or no, to act, or firmly decide to stand aside.

This is a man who says he knew what Burgess was up to for years, but could not bring himself to pick up the phone and tell the authorities. He says he had to be asked. At one point, for example, he went to his cousin, Tracy Barnes, then deputy director of the CIA, and said, 'Ask me about Cam- bridge.' Barnes said he wasn't interested in Cambridge, no doubt cringing at the thought of listening to .his ineffectual kinsman ramble on about undergraduate days. But, says Straight, 'I needed one beckoning gesture to lead me on. Without it I lacked the resolution to carry out my im- pulse.' Indeed, by his own description he lacked resolution. One wonders if this man has been able to procreate.

Instead of turning Burgess in, by Straight's account, he tried to get the spy to retire from the foreign service. Straight re- counts that he ran into Burgess in Washington in 1950 and gave him a ride in his car. He says he realised that Burgess had probably told the Communists secrets they needed to set the ambush on Korea's Yalu River, which almost cost the United States an army. This realisation seemed to call forth something akin to determination in Straight, although it would be thought of as no more than a quiver in another man: 'I no longer felt numb. Instead, anger rose within me. "You told me in 1949 that you were go- ing to leave the Foreign Office. You gave me your word."

"Did I say that? Perhaps I did. I believ- ed at the time that I was about to leave the Foreign Office," he added. "I actually did go on extended tour. I did almost leave when I returned, but they insisted on fin- ding another job for me. Then they posted me here."

"You broke your word to me," I said. "Yes. Well," he said, "this is where I am getting off if you will pull over." ' Did he turn him in? No, but 'I was ready at that moment to tell the authorities all I knew. With that in mind, I went to see the British official whom I knew best in Washington.

"I have some information about Guy Burgess that I wanted to give to the British government," I said. My friend smiled at me, and said, "You too?" "My dear fellow," he added, "you will have to take your place at the end of the line. And I should warn you, the line runs all the way

around the block." It was almost as if the British government did not want to hear what I and others had to say. It was all too embarrassing.'

Embarrassing? Well, Straight says that he got involved in the outer edges of treason when his friend at the University, John Cornford, was killed in the Spanish Civil War. He tells how this broke him up com- pletely and explains that he was such a shat- tered wreck that Anthony Blunt and friends were able to impose their will on him. The Kremlin, they told him, wanted him to go to America and be a mole. He was to work his way up in the field of high and interna- tional finance and, having succeeded, we presume he was to turn the Chase Manhat- tan Bank over to the Rooskies.

By his account, Straight thrashed against these orders. They were amended to merely going back to America, a place he had not been to since he was eight years old and with which he was completely out of touch, and there he was to hold himself in readiness for dark derring-do. Still, he resisted, but 'my pleas to be released had been reviewed by Stalin, so Anthony [Blunt] told me... and had been rejected, and I was trapped in a way that neither An- thony nor I could assess.' It strains creduli- ty to think of Red Ivan the Terrible late at night in his Kremlin cubicle reviewing assignments of undergraduate poofs and their heterosexual friend, Mr Michael Straight. One might have thought he would have found some pleasanter task for himself — say arranging for the shooting of that odd batch of ten thousand people he had almost forgotten about.

Straight arrives in the United States and goes to Washington where, thanks to wealth and the social connections of his family, he gets a private meeting with Franklin Roosevelt. So why not Stalin too? 'I went to sec Roosevelt [who knew a clunker when he was handed one] in his White House study,' writes our anti-hero. 'He tried to think of agencies that might take me on, and he gave up. "Why not get some outside experience and then join the government?" he said.' A characteristically Rooseveltian way of getting out of hiring this oddball and yet not giving an outright no, something FDR found hard to do.

In the end Straight wound up in the State Department as a volunteer. He went down to the office every morning and, by his own description, read the newspapers, cut in- teresting items out of them and used them as the factual basis to write reports. He had no access to cables or secrets or important meetings. He simply hung out, writing his reports from time to time. He says they were circulated and that he got pass grades on the margin from some of the big shots upstairs. Nevertheless, he says the Russians thought highly enough of this low-level penetration of high-level places to give him a control agent or espionage nanny.

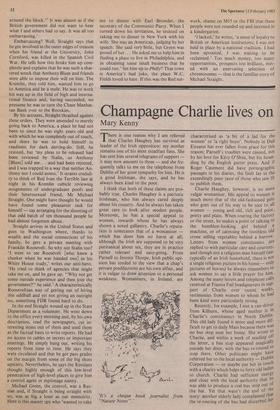

Michael Green, the control, was a Rus- sian and, if Straight is being straight with us, was as big a loser as our memoirist. Here is this master spy who 'wanted to take

me to dinner with Earl Browder, the secretary of the Communist Party. When I turned down his invitation, he insisted on taking me to dinner in New York with his wife. She was an American, judging by her speech. She said very little, but Green was proud of her... He asked me to help him in finding a place to live in Philadelphia, and in obtaining some small business that he could run.' Set him up in Phhlly? That town is America's bad joke, the place W.C. Fields loved to hate. If this was the Red net-

work, shame on M15 or the FBI that these people were not rounded up and interned in a kindergarten.

'I lacked,' he writes, 'a sense of loyalty to British or American institutions; I was not held in place by a national tradition. I had been uprooted, I was waiting to be reclaimed.' Too much money, too many opportunities, prospects too brilliant, mix- ed with an enervating selection of chromosomes — that is the familiar story of Michael Straight.

Previous page

Previous page