Where does it lie?

John McEwen

ART AND THE BEAUTY OF GOD by Richard Harries Mowbray, f14.99, pp. 150 Richard Harries is the Bishop of Oxford and this short book, dedicated 'to the clergy and people of his diocese' and subtitled 'A Christian Understanding', is designed to bring the 'increasing awareness of the spiritual dimension of the arts' with- in the compass of the Church:

Unless the Christian faith has an understand- ing and a place for the arts it will inevitably fail to win the allegiance of those for whom they are the most important aspect of life.

He addresses a pressing problem. The word 'spiritual' does seem to have been bandied about of late more than at any time since the 1960s, which marked — and this was surely the most important historical shift of that decade — a great withdrawal of Christian faith in western Europe. Now, after 30 years of Christianity going untaught in state education, we have a growing proportion of the population with no understanding at all of the aesthet- ic history of the West. No wonder people grope for a 'spiritual dimension' to their lives. Man cannot live by bread alone, as the sudden collapse of the Soviet Empire has shown. But in the arts and in western Europe an ingrained hatred of clericalism Persists, and through clericalism of authori- ty in any form.

The Bishop states the Christian case as follows:

It is central to Christianity, properly under- stood, that there is a resemblance, a relation- ship between the beauty we experience in nature, in the arts, in a genuinely good per- son and in God: and that which tantalises, beckons and calls us in beauty has its origin in God himself.

As a Protestant he deplores his church's Iconoclasm, comparing it unfavourably with Orthodox Christianity, in particular, which over the centuries has rarely lost sight of 'the beauty of God'.

Beauty partakes of wholeness, harmony and illumination of every kind, but only if it Is integral to truth. Truth is moral integrity, for the artist, artistic integrity; thus things that are ugly can be beautiful. Beauty is also objective, its characteristics discernible to all and definitely not in the subjective eye of the beholder. Kitsch is therefore its deceitful opposite — a moral, spiritual and aesthetic failure which nonetheless exposes their inseparability. The Bishop reserves his greatest contempt for kitsch as 'an enemy of the Christian faith'.

For a Christian the world is good both because God, who is supreme good, has created it and because, in the person of his Son, he has embraced it in human life. Even more than that, in the Resurrection he has raised earthly beauty to everlasting life. The Church has always rejected here- sies like Gnosticism and Manichaeism which taught that the physical world should be despised as being evil in itself or at least inferior to the supernatural. But there must nevertheless be a balance. Earthly beauty can only be properly appreciated and enjoyed when it is seen in the light of and in relation to the divine glory. He quotes St Augustine comparing this with a betrothed woman who says: The ring is enough, I do not want to see his face again'. But the ring is to be appreciated, the giver is to be loved. God in his love is supreme beauty making each of us 'a creative artist in rela- tion to life itself.

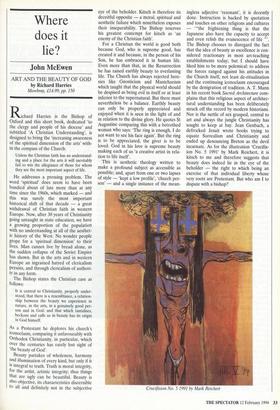

This is aesthetic theology written to make a profound subject as accessible as possible; and, apart from one or two lapses of style — 'kept a low profile', 'church per- son' — and a single instance of the mean- ingless adjective 'resonant', it is decently done. Instruction is backed by quotation and touches on other religions and cultures — "the frightening thing is that the Japanese also have the capacity to accept and even relish the evanescence of life "'. The Bishop chooses to disregard the fact that the idea of beauty as excellence is con- sidered reactionary in most art-teaching establishments today; but I should have liked him to be more polemical: to address the forces ranged against his attitudes in the Church itself, not least de-ritualisation and the continuing iconoclasm encouraged by the denigration of tradition. A. T. Mann in his recent book Sacred Architecture com- plains that this religious aspect of architec- tural understanding has been deliberately struck off the record by modern historians. Nor is the nettle of sex grasped, central to art and always the jungle Christianity has sought to keep at bay. Jean Genbach, a defrocked Jesuit wrote books trying to equate Surrealism and Christianity and ended up denouncing Breton as the devil incarnate. As for the illustration 'Crucifix- ion No. 5 1991' by Mark Reichert, it is kitsch to me and therefore suggests that beauty does indeed lie in the eye of the beholder — the right to which being an exercise of that individual liberty whose very roots are Protestant. But who am I to dispute with a bishop?

Crucifixion No. 5 1991 by Mark Reichert

Previous page

Previous page