MAD ABOUT SAFFRON

India's flexible character is being

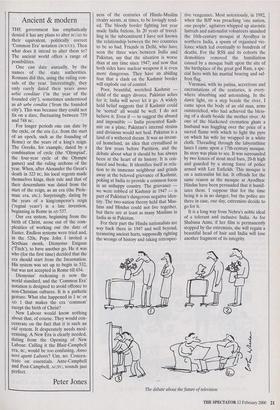

ravaged by Hindu fundamentalists, says Trevor Fishlock Varanasi MILKY morning light revealed the jum- bled outlines of India's holiest city: the temples, shrines, ashrams, palaces, crema- tion sites, tea shops and ghats, the worn river steps where pilgrims rinsed away their sins in the brown Ganges. On one of the ghats cameras and lights had been set up and the screen goddess Shabana Azmi, her head shaved for her starring role, was ready for the first scene of a new movie.

The action, though, was not in the script. Hundreds of yelling Hindu extremists " descended on the set, smashing and burn- ing. Filming stopped. A couple of protesters promised to drown themselves in the holy river if the cameras rolled. 'All in the cause of saffronisation,' an Indian friend said. Saf- fron has for many centuries been the emblematic Hindu colour and today the word is shorthand for Hindu nationalism and, in particular, for fundamentalism.

The skirmish by the Ganges angered many people. 'This is another attempt,' said my friend, 'to dictate what we read and see.' He didn't shrug it off. The saf- fron extremists have a history of supplying brute force to political protest and have killed many people. The Varanasi riot was only partly about a controversial film; it was also an incident in a long struggle by Hindu fundamentalists to change and define India.

The shaved head of the enchanting Sha- bana Azmi may be seen as symbolic. She cut off her hair to play the part of a widow in a film intended to explore the plight of Hindu women made virtual outcasts by their loss of married status. The rowdies assumed the film would offend Hindu sensibilities, not least because it is directed by Deepa Mehta, who once upset people with a movie depict- ing the taboo subject of lesbianism.

If the filming is stopped for good the bullies and bigots will claim another small victory for Hindutva. The word means `Hinduness' and encapsulates the funda- mentalist proposition that Hinduism is superior to any other faith, that Hindus are the original and only creators of Indian culture and are, exclusively, the Indian nation. By extension, the minorities of India, especially Muslims and Christians, had better know their secondary place; or else.

This manifesto opposes the secular polity created by Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister. He warned against Hindu extremism and believed that India must be its paradoxical and difficult self: a flexible, layered, diverse and democratic society. Given its multiplicity of languages and faiths, and the varied mosaic of Hinduism itself — a marvel of beliefs and rituals, without pope, prophet, orthodoxy or single, defining holy book — what else could it be and how else could it be managed?

Nationalists, however, relentlessly pursue the illusion that Indian identity can be redefined by squeezing its diversity into the iron frame of a Hindu state. Hindu con- sciousness grew in the 1870s in reaction to the Raj and to Christian missions. It took a militant form in 1925 with the founding of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the RSS. It kitted out its cadres with white shirts and British police-style baggy khaki shorts, and imposed a martial discipline. In developing its ideology one of its leaders expressed admiration for Nazi purging of the Jews. The RSS grew into a well-organ- ised paramilitary-style nationalist machine and spawned a number of offshoots, at least one of them thuggish. The BJP, the Bharatiya Janata Party, which now forms the government, is the RSS's political arm.

The foundation stone of the RSS is the invented tradition that there was an ancient Hindu golden age ended by Muslim inva- sion 1,000 years ago. Hindus, according to nationlist teaching, were humiliated vic- tims who should assertively regain their pri- macy in their own land. They are also persuaded that they are a vulnerable minority in spite of the fact that they are the overwhelming majority. Hindus are 83 per cent of India's population and Muslims 11 per cent; but nationalists suggest that Hindus are an island in an Islamic ocean and that Muslims intend to outbreed them. There is an idea that Indian Muslims are a fifth column, not truly committed to India: `They cheer for Pakistan in Test matches.'

From the film-set rampage beside the Ganges the trail leads depressingly back- wards to the tragic watershed of Partition. Fifty-three years on, in both India and Pak- istan, old paranoias flourish and the bitter- ness of the centuries of Hindu-Muslim rivalry seems, at times, to be lovingly tend- ed. The bloody border fighting last year made India furious. In 20 years of travel- ling in the subcontinent I have not known the relationship between the two countries to be so bad. Friends in Delhi, who have seen the three wars between India and Pakistan, say that the situation is worse than at any time since 1947; and now that both sides have nuclear weapons it is even more dangerous. They have an abiding fear that a clash on the Kashmir border will explode out of control.

Poor, beautiful, wretched Kashmir child of the angry divorce. Pakistan aches for it; India will never let it go. A widely held belief suggests that if Kashmir could be 'sorted' all would be well. I do not believe it. Even if — to suggest the absurd and impossible — India presented Kash- mir on a plate, Pakistan's internal strains and divisions would not heal. Pakistan is a land of a withered dream. It was an invent- ed homeland, an idea that crystallised in the few years before Partition, and the debate about what it should be has always been at the heart of its history. It is con- fused and broke. It identifies itself in rela- tion to its immense neighbour and grinds away at the beloved grievance of Kashmir, poking at India to provide a common focus in an unhappy country. The grievance we were robbed of Kashmir in 1947 — is part of Pakistan's dangerous negative iden- tity. The two-nation theory held that Mus- lims and Hindus could not live together, but there are at least as many Muslims in India as in Pakistan.

For their part the Hindu nationalists are way back there in 1947 and well beyond, treasuring ancient hurts, supposedly righting the wrongs of history and taking retrospec- tive vengeance. Most notoriously, in 1992, when the BJP was preaching 'one nation, one people', agitators whipped up atavistic hatreds and nationalist volunteers smashed the 16th-century mosque at Ayodhya in northern India, a spasm of organised vio- lence which led eventually to hundreds of deaths. For the RSS and its cohorts the demolition removed the humiliation caused by a mosque built upon the site of the birthplace of the great god Ram, a spe- cial hero with his martial bearing and saf- fron flag.

Varanasi, with its patina, accretions and encrustations of the centuries, is every- where absorbing and astonishing. In the dawn light, on a step beside the. river, I came upon the body of an old man, arms outstretched, who had achieved the bless- ing of a death beside the mother river. At one of the blackened cremation ghats a husband was haggling over the price of a sacred flame with which to light the pyre on which his wife lay wrapped in a white cloth. Threading through the labyrinthine lanes I came upon a 17th-century mosque. Its story was plain to see. It was surrounded by two fences of stout steel bars, 20-ft high and guarded by a strong force of police armed with Lee Enfields. This mosque is on a nationalist hit list. It offends for the same reason as the mosque at Ayodhya: Hindus have been persuaded that it humil- iates them. I suppose that for the time being it is in no danger, but the police are there in case, one day, extremists decide to go for it.

It is a long way from Nehru's noble ideal of a tolerant and inclusive India. As for Shabana Azmi, if her film is permanently stopped by the extremists, she will regain a beautiful head of hair and India will lose another fragment of its integrity.

The debate about the future of television

Previous page

Previous page