New Zealand Letters of Thomas Arnold the Younger, and Letters

of Arthur Hugh Cough edited by James Bertram (University of Auck- land and OUP 80s)

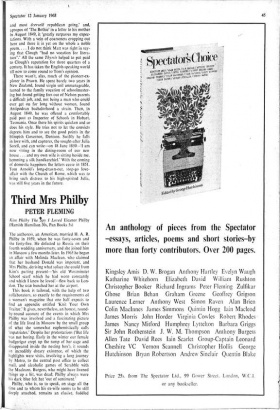

Amorous prawn

DAVID WILLIAMS

Thomas was Arnold of Rugby's favourite son. The Doctor's nickname for him was 'Prawn.' What prompted the name we shan't now ever know; it's the kind that ought to suit somebody small, somebody relying, for his quiet life, on the effectiveness of a defensive shell. But Tom Arnold wasn't like that at all. He was tall and handsome, a bit blundering in his social re- lationships; he took a First in Greats; he was impulsive and anti-establishment—indeed quite a hot-breathing revolutionary, restless and un- easy in early Victorian England with power and privilege still firmly vested in the hands of a tiny few; he fell in love easily; he see-sawed quite spectacularly between unbelief and belief. Clough immortalised him in 'The Bothie,' where he called him: 'Hewson the radical hot, hating lords and scorn- ing ladies, Silent mostly, but often reviling in fire and fury Feudal tenures, mercantile lords, competition and bishops, Liveries, armorial bearings, amongst other things the Game-laws; He could speak, and was asked-to by Adam, but Lindsay aloud cried (Whiskey was hot in his brain) Confound it, no, not Hewson, A'nt he cock-sure to bring in his eternal political humbug?'

The Arnolds, of course, like the Stephens, the Macaulays and the Wedgwoods, are one of England's mandarin families. Tom himself can't, I suppose, be said to have achieved any- thing especially notable (though he must have been nice to know), but he was the father of Mrs Humphry Ward, a woman of most for- midable accomplishment, and grandfather of Julian and Aldous Huxley.

Tom wasn't creative then, but these letters of his from New Zealand and later Tasmania bring to life a most likeable personality even if they tell us disappointingly little about early colonising days in the Antipodes at the end of the 1840s. They were sent across the world on their six-months journey to his family at Pox How in the Lake District, or to Arthur Hugh Clough. At the beginning of the series Clough' is still a fellow of Oriel, but by the end, after his rejection of orthodoxy and the Thirty-nine Articles, has taken up residence at University Hall, Gordon Square-111e Stincomalean position' as he sadly calls it. Eight letters from Clough to Tom Arnold are also printed here, together with one or two gossipy, affectionate ones from his mother or-sisters, and as an end- piece there are the so-called 'Equator Letters,' written by Arnold to J. C. Shairp during the course of his long voyage out.

Clough's letters give the book a distinction wouldn't otherwise otherwise have, and although the bulk' of these have already appeared in Professor Mulhauser's admirable 1957 edition of Clough's letters, the unpruned versions we get here 4:1Ol add something of value. The Equator letters trace without much novelty the familiar pro- gress of a Victorian intellectual from the glad, confident morning of Anglican conformism towards some form of personal faith stripped of ancient formularies and not blandly blind' to the grievous social injustices suffered by 98 per cent of his fellow-countrymen. 'Thanks be to God and to George Sand' Tom says— coupling that tigress, used to famous partners,'; with one that even she might have found diffi- cult to dominate—% . I found that this misery, which I had been so anxious to alleviate on the assumption that it could not but exist, was altogether an outrage and an offence in the sight of God.'

Is there enough in this volume to justify all• the careful scholarship which Professor Bertram of the University of Wellington brings to it? Well, lust about, though the crop in this par- ticular strawberry bed has, for the most part, already been picked and bottled. The book is chiefly valuable in that it succeeds in demon- strating for us the admiration—veneration almost—a gifted youngster like Tom Arnold had for Clough, who is slowly emerging as one of the major mid-nineteenth-century figures with more to say to our own generation' than perhaps any other writer of his time. Tom's more famous brother, Matthew, wrote his Thyrsis six years after Clough's early death. It is a lush poem, murmurous with hot-house melancholy over what he feels to have been Clough's wasted life. Matthew Arnold certainly meant no unkindness, but he was convinced, as his letters show, that Clough never found his métier as a writer. (Not unprofound, not un- grand, not unmoving—but unpoetical' is one of his typical comments.)

Tom Arnold won't have any part in this attitude. For him Clough in 1848 is 'the wildest and most ecerveM republican going,' and, apropos of 'The_ Bothie' in a letter to his mother in August 1849, it 'greatly surpasses my expec- tations. With a vein of coarseness cropping out here and there it is yet on the whole a noble poem.... I do not think Matt was right in say-, ing that Clough "had no vocation for litera- ture".' All the same Thyrsis helped to put paid to dough's reputation for three quarters of a century. It has taken the English-speaking world till now to come round to Tom's opinion.

There wasn't, alas, much of the pioneer-ex- plorer in Prawn. He spent barely two years in New Zealand, found virgin soil unmanageable, turned to the family vocation of schoolmaster- ing but found getting fees out of Nelson parents a difficult job, and, not being .a man who could ever get on for long without women, found Antipodean bachelorhood a strain. Then, in August 1849, he was offered a comfortably paid post as Inspector of Schools in Hobart, Tasmania. Once there his spirits quicken and so does his style. He tries not to let the convicts depress him and to see the good points in the blimpish Governor, Denison. Swiftly he falls in love with, and captures, the sought-after Julia Sorell, and can write—on 18 June 1850-1 am now fitting in the dining-room of our new house. . . and my own wife is sitting beside me, hemming a silk handkerchief.' With the coming of domestic happiness the letters cease in 1851. Tom Arnold's long-drawn-out, stop-go love- affair with the Church of Rome, which was to bring such distress to his high-spirited Julia, was still five years in the future.

Previous page

Previous page