Exhibitions

Gracious living

Giles Auty

0 ne great blessing of my life is that I have seldom experienced envy. Even when driving past the stately houses belonging to ancient families or to the lately rich I tend to think of maintenance costs and discom- fort rather than imagine myself hosting glittering receptions. Experience has taught me I was possibly not born to be a landowner. When I bought some acres a few years ago to keep ducks I saw more foxes in a week than the Quorn probably spot in a season. The draughty farmhouse to my damp acres rejoiced in the name Rockville. When I searched the land reg- istry for a more imposing, or at least attractive earlier name, I found the proper- ty was registered formerly as Parc Uren. At present I own nothing more than a Victorian house which enjoys the imagined advantages of being within a conservation area. This has not been enough to prevent my architect neighbour erecting a 500- square-foot building which rises to more than 20 feet along the wall of my boundary. This imposing edifice is simply to house a minuscule swimming-pool. The revised aspect from my garden resembles nothing so much as looking up at the bridge of a corvette.

One of the two excellent exhibitions on at Christie's at present (8 King Street, SW1) deals with some of the art, furniture and objets which have been accepted in lieu of death duty/inheritance tax but have been allowed to remain in situ in the great houses for which they were first commis- sioned. The benefit to the public is that it can normally see these wonderful artefacts in the settings for which they were original- ly designed. Two of the fine houses fea- tured in the exhibition are from Cornwall, a county also lucky enough to boast Parc Uren. Antony House and Cotehele both belong now to the National Trust. The same ownership applies also now to some of the other great houses featured at Christie's: Belton House, Coughton Court, Hardwick Hall, Kedleston Hall, Knole, Nostell Priory, Shugborough, Sudbury Hall and Uppark; while Brodie Castle and Haddo House are now owned by the National Trust for Scotland. By contrast, Hagley Hall and Sledmere House are lived

in and owned still by descendants of the families which first built them.

It is first to Arundel, which enjoys the status of private charitable trust, that we should look, however, for a great pair of full-length portraits by Daniel Mytens. These show the Earl and Countess of Arundel and allude also, through the backgrounds, to the couple's great zeal as collectors. Thomas Howard, second Earl of Arundel, owned a collection of art and antiquities surpassed only by that of Charles I. Other notable paintings include the Strozzi from Kedleston, three Batonis from Uppark, of which the portrait of Sir Matthew Fetherstonhaugh is by some way the best, and two important English por- traits. The first, by John Constable, is of Henry Greswolde Lewis of Weston Park, while the second, by John Everett Millais, is of Cardinal Newman, who became one of Rome's more famous converts in 1845. Unsurprisingly, this latter portrait was

bought by the 15th Duke of Norfolk, a former pupil of Oratory School, which was founded by Newman. The Kedleston Rem- brandt that isn't and wasn't is also featured and reminds me of a notable country family who discovered an early newspaper report which described them as owning a Rembrandt. When asking me to help them identify it I was told: 'We have rather a lot of paintings but aren't sure which one is supposed to be the Rembrandt.'

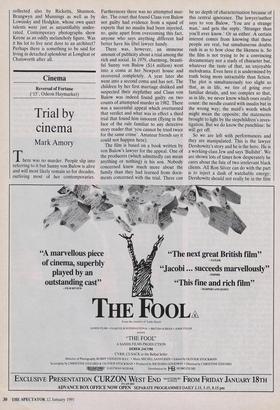

Christie's second exhibition, of works by the artist and illustrator Charles Keene (1823-1891), is more modest in pretension but no less rewarding. Keene is remem- bered by many principally as an illustrator for Punch, yet his work was admired by Camille Pissarro and collected by Degas. He was a draughtsman of unusual author- ity and talent, as more than 160 small works will reveal to those unacquainted previously with his mastery of line. Keene was an 'artist's artist' above all and was 'Sir Matthew Fetherstonhaugh', by Pompeo Girolamo Batoni, at Uppark collected also by Ricketts, Shannon, Brangwyn and Munnings as well as by Lowinsky and Hodgkin, whose own quiet talents were just as unjustifiably under- rated. Contemporary photographs show Keene as an oddly melancholy figure. Was it his lot to live next door to an architect? Perhaps there is something to be said for living in detached splendour at Longleat or Chatsworth after all.

Previous page

Previous page