THE POLITICS OF BLOODY MURDER

Peter °borne says that the Saville inquiry shows that Tony Blair

is prepared to extend clemency to terrorists but not to the British soldiers who were asked to protect us from them

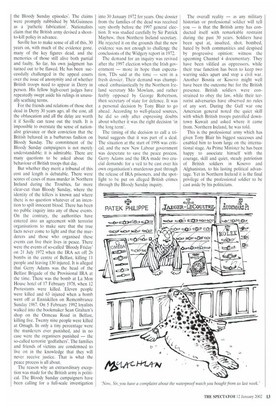

THERE has been plenty to turn the stomach along the road to peace in Northern Ireland: the deals done with murderers, the early release from prison of the terrorists, the proposed amnesty for those on the run.

Most people find this repellent and disquieting. Yet they are resigned to it because they accept that in Northern Ireland the only way forward is by casting a veil of obscurity over the past.

There is one exception to this rule: the British army. While the crimes of loyalist and IRA terrorists have been deliberately forgotten and overlooked, the conduct of soldiers is being put under a microscope by the Saville public inquiry into Bloody Sunday, set up by Tony Blair in early 1998.

Saville is certain to become the longest and most expensive tribunal in British history, and bears comparison only with the trial of Warren Hastings at the end of the 18th century. Already four years old, it is unlikely that it will reach a conclusion before 2004. The costs defy belief. A statement quietly released to Parliament just before Christmas showed that costs to the Northern Ireland Office alone have climbed to £53 million, and are estimated to reach £100 million by the end. The statement was disingenuous. The Ministry of Defence and other government departments have also incurred huge expenses: the total bill is likely to be close to an epic £200 million.

Most of this money is being paid out to lawyers. The British soldiers alone, facing allegations of murder, have almost a score of QCs between them. Last month the rate for senior barristers involved in the inquiry was lifted from £1,500 a day to £1,750 a day, with £750 a day in preparation rates and £125 an hour for travel costs. Junior barristers' rates were lifted from £750 to £875, while their preparation costs went up from £100 to £125.

The inquiry is setting other records, besides being by far the most expensive in history. The opening statement by Christopher Clarke QC, counsel to the tribunal, took a monumental three months. He was on his feet for 176 hours. Fellow lawyers feel sympathy for Clarke. They say that he was on the verge of being made a judge when he accepted his role in the tribunal, which was not expected to last far beyond six months. Clarke has had to wait a good five years longer than expected. It all proved too much for one member of the panel of judges, the New Zealander Sir Edward Somers, who stepped down for personal reasons last year amid reports that he found it hard to get home as much as he would like.

Nobody, however, can challenge the thoroughness of Lord Saville, a commercial lawyer who was appointed, according to legal gossip at the time, partly on the recommendation of the Prime Minister's close friend Charles Falconer QC. He has taken statements or oral evidence from more than 1,500 witnesses so far, with plenty to come.

The hearings take place in Derry's Guildhall, the fine Victorian building in the centre of the city which is less than a mile from the Rossville Flats area where the tragedy took place. It was almost exactly 30 years ago, on 30 January 1972, that some 5.000 people set off from the Bogside on a civil-rights march to protest against internment, the system of arrest without trial imposed by Edward Heath's government (and against which military chiefs had, ironically enough, fruitlessly protested). The authorities declared the march illegal, but that did not stop the protesters setting off for their objective: the Guildhall Square where the inquiry is being held today.

Army roadblocks prevented the marchers from leaving the Bogside and, as the crowd built up, rioting started. Bricks and bottles were thrown at the soldiers, who included members of the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment. In due course, shooting started, and barely 20 minutes later 13 people lay dead. A fourteenth was to die of his injuries several months later. Accounts of what happened are painful to read.

The outrage was immense. Patrick Hillery. then Irish foreign minister and later to become president of the Republic, declared that 'from now on my aim is to get Britain out of Ireland'. The British embassy in Dublin was burnt down. In the House of Commons, the MP Bernadette Devlin accused the home secretary Reginald Maudling of lying, declared that 'I have the right as the only representative in the House who was an eyewitness to ask a question of that murdering hypocrite', rushed across the floor of the Commons and struck Maudling in the face.

The nationalists are convinced that British troops were guilty of cold-blooded, premeditated murder on Bloody Sunday. The British army claimed from the start that the shooting was started by the IRA in a deliberate attempt to provoke a response. Early in the inquiry evidence was produced from intelligence sources that Martin McGuinness — a very senior commander in the provisional IRA in Derry at the time, a fact which this month's Channel 4 documentary on Bloody Sunday characteristically ignores — fired the first shot. According to the report, McGuinness admitted to an informer code-named Infliction that he had 'personally fired the shot from Rossville Flats in the Bogside that had precipitated the Bloody Sunday episodes'. The claims were promptly rubbished by McGuinness as a 'pathetic fabrication'. Nationalists claim that the British army devised a shootto-kill policy in advance.

Saville has to make sense of all of this, 30 years on, with much of the evidence gone, many of the key figures dead, and the memories of those still alive both partial and faulty. So far, his own judgment has turned out to be flawed. He has been successfully challenged in the appeal courts over the issue of anonymity and of whether British troops need to appear in Derry in person. His fellow high-court judges have repeatedly swept aside his rulings in unusually scathing terms.

For the friends and relations of those shot dead in Derry 30 years ago, all the cost, all the obfuscation and all the delay are worth it if Saville can tease out the truth. It is impossible to overstate the sense of nationalist grievance or their conviction that the British behaved in a barbarous fashion on Bloody Sunday. The commitment of the Bloody Sunday campaigners is not merely understandable; it is admirable. There are many questions to be asked about the behaviour of British troops that day.

But whether they merit a tribunal of this cost and length is debatable. There were scores of cases of mass murder in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, far more clear-cut than Bloody Sunday, where the identity of the killers is known and where there is no question whatever of an intention to spill innocent blood. There has been no public inquiry into any of these events. On the contrary, the authorities have entered into an agreement with terrorist organisations to make sure that the true facts never come to light and that the murderers and those who organised these events can live their lives in peace. There were the events of so-called 'Bloody Friday' on 21 July 1972 when the IRA set off 26 bombs in the centre of Belfast, killing 11 people and leaving 130 injured. It is alleged that Gerry Adams was the head of the Belfast Brigade of the Provisional IRA at the time. There was the bomb at La Mon House hotel of 17 February 1978, when 12 Protestants were killed. Eleven people were killed and 63 injured when a bomb went off at Enniskillen on Remembrance Sunday 1987. On 5 February 1992 loyalists walked into the bookmaker Sean Graham's shop on the Ormeau Road in Belfast, killing five. Twenty nine people were killed at Omagh. In only a tiny percentage were the murderers ever punished, and in no case were the organisers punished — the so-called terrorist 'godfathers'. The families and friends of victims are condemned to live on in the knowledge that they will never receive justice. That is what the peace process is all about.

The reason why an extraordinary exception was made for the British army is political. The Bloody Sunday campaigners have been calling for a full-scale investigation into 30 January 1972 for years. One dossier from the families of the dead was received very shortly before the 1997 general election. It was studied carefully by Sir Patrick Mayhew. then Northern Ireland secretary. He rejected it on the grounds that the new evidence was not enough to challenge the conclusions of the Widgery report in 1972.

The demand for an inquiry was revived after the 1997 election when the Irish government — more in hope than expectation, TDs said at the time — sent in a fresh dossier. Their demand was championed enthusiastically by the Northern Ireland secretary Mo Mowlam, and rather feebly opposed by George Robertson, then secretary of state for defence. It was a personal decision by Tony Blair to go ahead, According to well-placed sources, he did so only after expressing doubts about whether it was the right decision in the long term'.

The timing of the decision to call a tribunal suggests that it was part of a deal. The situation at the start of 1998 was critical, and the new New Labour government was desperate to save the peace process. Gerry Adams and the IRA made two crucial demands: for a veil to be cast over his own organisation's murderous past through the release of IRA prisoners, and the spotlight to be put on alleged British crimes through the Bloody Sunday inquiry. The overall reality — as any military historian or professional soldier will tell you — is that the British army has conducted itself with remarkable restraint during the past 30 years. Soldiers have been spat at, insulted, shot, bombed, hated by both communities and despised by progressive opinion: witness the upcoming Channel 4 documentary. They have been vilified as oppressors, while their true function has been to keep two warring sides apart and stop a civil war. Another Bosnia or Kosovo might well have been the outcome but for the British presence. British soldiers were constrained to obey the law, while their terrorist adversaries have observed no rules of any sort. During the Gulf war one American general noted the quiet skill with which British troops patrolled downtown Kuwait and asked where it came from. Northern Ireland, he was told.

This is the professional army which has given Tony Blair his biggest successes and enabled him to loom large on the international stage. As Prime Minister he has been happy to associate himself with the courage, skill and quiet, steady patriotism of British soldiers in Kosovo and Afghanistan, to his lasting political advantage. Yet in Northern Ireland it is the final privilege of the professional soldier to be cast aside by his politicians.

Previous page

Previous page