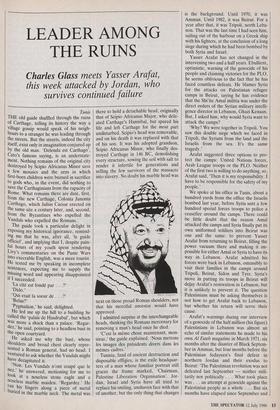

LEADER AMONG THE RUINS

Charles Glass meets Yasser Arafat,

this week attacked by Jordan, who survives continued failure

Tunis THE old guide shuffled through the ruins of Carthage, telling its history the way a village gossip would speak of his neigh- hours to a stranger he was leading through the streets. But the streets, indeed the city itself, exist only in imagination conjured up by the old man. Delenda est Carthago', Cato's famous saying, is an understate- ment. Nothing remains of the original city destroyed by Scipio Africanus Minor save a few mosaics and the urns in which first-born children were burned in sacrifice to gods who, in the event, did nothing to save the Carthaginians from the rapacity of Rome. What remains there are date, first, from the new Carthage, Colonia Junonia Carthago, which Julius Caesar erected on the same site a century later, and, second, from the Byzantines who expelled the Vandals who expelled the Romans. The guide took a particular delight in exposing my historical ignorance, remind- lag me that he was, after all, 'le guide officiel', and implying that I, despite pain- ful hours of my youth spent rendering Livy's commentaries on the Punic Wars Into execrable English, was a mere tourist. He tested me by speaking in incomplete sentences, expecting me to supply the missing word and appearing disappointed if I succeeded.

`La cite est fonde par . . .?' `Dido.'

'Qui etait la soeur de . . .?'

'Belus?'

`Pygmalion,' he said, delighted. He led me up the hill to a building he called the `palais de Hasdrubal', but which was more a shack than a palace. `Regar- dez,' he said, pointing to a headless bust in the open courtyard. He asked me why the bust, whose shoulders and broad chest clearly repre- sented a Roman general, had no head. I ventured to ask whether the Vandals might have decapitated it. `Non. Les Vandals n'ont coupe que le nez,' he answered, motioning for me to look at a noseless stone eagle and a noseless marble maiden. `Regardez.' He ran his fingers along a piece of metal buried in the marble neck. The metal was there to hold a detachable head, originally that of Scipio Africanus Major, who defe- ated Carthage's Hannibal, but spared his life and left Carthage for the most part undisturbed. Scipio's head was removable, and on his death it was replaced with that of his son. It was his adopted grandson, Scipio Africanus Minor, who finally des- troyed Carthage in 146 BC, demolishing every structure, sowing the soil with salt to render it infertile for generations and selling the few survivors of the massacre into slavery. No doubt his marble head was next on those proud Roman shoulders, not that his merciful ancestor would have approved. I admitted surprise at the interchangeable heads, thinking the Romans mercenary for removing a man's head once he died. `C'est la meme chose maintenant, mon- sieur,' the guide explained. 'Nous mettons les images des presidents divers dans les memes cadres.'

Tunisia, land of ancient destruction and disposable effigies, is the exile headquar- ters of a man whose familiar portrait still graces the frame marked, 'Chairman, Palestine Liberation Organisation'. Jor- dan, Israel and Syria have all tried to replace his smiling, unshaven face with that of another, but the only thing that changes is the background. Until 1970, it was Amman. Until 1982, it was Beirut. For a year after that, it was Tripoli, north Leba- non. That was the last time I had seen him, sailing out of the harbour on a Greek ship with his fighters, at the conclusion of a long siege during which he had been bombed by both Syria and Israel.

Yasser Arafat has not changed in the intervening two and a half years. Ebullient, optimistic, warning of the genocide of his people and claiming victories for the PLO, he seems oblivious to the fact that he has faced countless defeats. He blames Syria for the attacks on Palestinian refugee camps in Beirut, saying he has evidence that the Shi'ite Amal militia was under the direct orders of the Syrian military intelli- gence director in Lebanon, Ghazi Kenaan. But, I asked him, why would Syria want to attack the camps?

`Why? We were together in Tripoli. You saw this double siege which we faced in Tripoli, the Syrians from the land and the Israelis from the sea. It's the same tragedy.'

Arafat suggested three options to pro- tect the camps: United Nations forces, Arab League troops or the PLO. Neither of the first two is willing to do anything, so, Arafat said, 'Then it is my responsibility. I have to be responsible for the safety of my people.'

We spoke at his office in Tunis, about a hundred yards from the office the Israelis bombed last year, before Syria sent a few hundred special forces troops to police a ceasefire around the camps. There could be little doubt that the reason Amal attacked the camps and Syria finally put its own uniformed soldiers into Beirut was one and the same: to prevent Yasser Arafat from returning to Beirut, filling the power vacuum there and making it im- possible for either Amal or Syria to have its way in Lebanon. Arafat admitted his forces were back in Lebanon, ostensibly to visit their families in the camps around Tripoli, Beirut, Sidon and Tyre. Syria's move in putting its troops in Beirut will delay Arafat's restoration in Lebanon, but it is unlikely to prevent it. The question Palestinians must be asking themselves is not how to get Arafat back to Lebanon, but whether his return will serve their cause.

Arafat's warnings during our interview of a genocide of the half million (his figure) Palestinians in Lebanon was almost an echo of similar statements he made to his own Al Fateh magazine in March 1971, six months after the disaster of Black Septem- ber in Amman, but four months before the Palestinian fedayeen's final defeat in northern Jordan and their exodus to Beirut: 'The Palestinian revolution was not defeated last September — neither mili- tarily nor politically . . . What took place was . . . an attempt at genocide against the Palestinian people as a whole . . But six months have elapsed since September and the revolution is here to stay with all its leadership . . . the revolution which was able last September to withdraw its head from under the guillotine — this revolution will never end or be brought to its knees.' Neither the rhetoric nor the hopelessness of the Palestinians, both refugees and those under occupation, has changed much since then.

Issam Sartawi, the physician and Palesti- nian politician whose plainspeaking and willingness to compromise led to his mur- der by fellow Palestinians in 1983, was one of the first to take the wind out of Arafat's sails after the 'victory' in Beirut when the PLO withdrew in 1982: he said that with another victory like Beirut the next PLO executive committee meeting would take place in Fiji. Sartawi was critical of the Palestinian leadership as a whole. I once asked him why the Palestinians had had such poor leaders, from Haj Amin Hus- seini who led them to defeat in 1948 to Ahmed Shukairy, the first PLO head, who is remembered today only for his statement that he would throw the Jews into the sea. `We had a good leader in Palestine once,' Sartawi said, tut we crucified him.'

Arafat's ambiguous approach to achiev- ing his goals has brought him enemies for all the wrong reasons. Syria opposes him, and is acting against him now in Lebanon, because he pursued a diplomatic option. Jordan opposes him, has just expelled his Al Fateh colleagues from Amman and is trying to co-opt him in the West Bank and Gaza, because he pursued the armed strug- gle. What most interests Arafat loyalists is that Syria and Jordan, while they disagree on the question of compromise with Israel, are on good terms with each other and agree that Yasser Arafat's head must come off the statue. Still, Arafat survives, even against established survivors hike Syria's Hafez al-Assad and Jordan's King Hus sein.

This is a time for soul-searching among Palestinians, not that there have been many times since 1948 when they could avoid wondering what went wrong. Those PLO people in Damascus who fought against Arafat in 1983 at Syria's behest would like some accommodation with the Old Man, but Syria will not permit a reconciliation yet. Arafat's own loyalists are discussing what to do next, whether some wholly new stategy ought to be adopted. Arafat said they were discussing things like urging Palestinians in Israel and the occupied territories to imitate the blacks in South Africa with non-violent civil disobedience and mass demonstra- tions. Another idea is a return to Lebanon, to give the PLO a military base again now that the US and Israel have firmly closed the door to Arafat's diplomatic overtures. Both courses have their pros and cons. Civil disobedience would be difficult to organise among a population as outnum- bered and controlled as the Arabs in Israel are, and there is no guarantee everyone would respond if Arafat did call a strike; but such a scheme would have a tremendous impact in Israel and the US if it worked.

Returning to Lebanon would invite Sy- rian and Israeli attack, and it could not help but involve the PLO once again in Lebanon's internal conflict. Arafat would however be welcomed by many people: the Christian President Amin Gemayel, who would like to see someone else opposing Syria; the Iranian-backed Hizballah, the Party of God, which already has a working alliance with Arafat to fight the Israelis in south Lebanon and to oppose the Amal militia; and most of the Sunni Muslim population of west Beirut, who regard Arafat as a natural ally in opposing the Shi'ites and in establishing some kind of order. Even the US Embassy might be glad to see him return, although no American official can say so, because it could reopen under his protection as it was until 1982.

`What you guys don't understand,' a Palestinian friend from Nazareth said, re- ferring to the foreign press, 'is that Arafat represents no threat to anybody. All he wants is to have his picture taken on the White House lawn and give his people houses and the chance to buy video games.'

Arafat is as far today from that modest goal as he ever was. By any standard, he has failed his people. Under his leadership, they were massacred and their fighters were driven out of Jordan. They fought the Israelis in the occupied territories and in Lebanon, but they paid a terrible price Israeli bombardment and butchery by Lebanese Christians and, latterly, Shi'ite Muslims. Yet his head is still on his shoulders, and most Palestinians regard him as their leader. David Hirst wrote, in The Gun and the Olive Branch (Faber, 1984), of Palestinian leaders who led the disastrous revolt against the British in 1936, 'The traditional leadership may not have enjoyed much respect, but it was the only leadership the Arabs had; deservedly or not, it was symbolic of their aspirations . . . .' As 'le guide officel' might have said, `Plus ca change, plus . . .

Previous page

Previous page