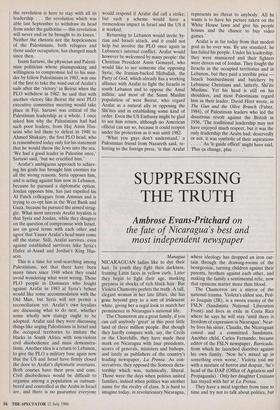

SUPPRESSING THE TRUTH

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard on the fate of Nicaragua's best and most independent newspaper

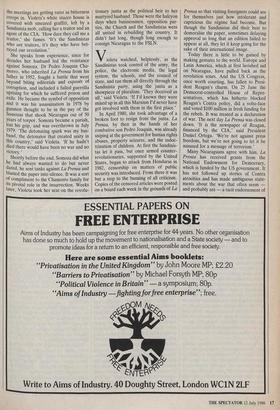

Managua NICARAGUAN ladies like to dye their hair. In youth they fight their darkness, framing Latin faces in yellow curls. Later they begin to fight their age, masking greyness in shocks of rich black hair. But Violeta Chamorro prefers the truth. A tall, elegant woman in her late fifties, she has gone beyond grey to a sort of iridescent white, giving her a regal look to match her prominence in Nicaragua's national life.

The Chamorros are a great family, if you can call anybody 'great' in this poor little land of three million people. But though they hardly compare with, say, the Cecils or the Churchills, they have made their mark on Nicaragua with four presidents, scores of generals, ministers and bishops, and lately as publishers of the country's leading newspaper, La Prensa. As con- servatives, they opposed the Somoza dicta- torship which was, technically, liberal. Those were the days when politics united families, indeed when politics was another name for the rivalry of clans. It is hard to imagine today, in revolutionary Nicaragua, where ideology has dropped an iron cur- tain through the drawing-rooms of the bourgeoisie, turning children against their parents, brothers against each other, and making the family a sentimental relic, now that opinions matter more than blood.

The Chamorros are a mirror of the national trauma. Violeta's eldest son, Ped- ro Joaquin (JR), is a sworn enemy of the FSLN (Sandinista National Liberation Front) and lives in exile in Costa Rica where he says he will stay 'until there is freedom of expression in Nicaragua'. Near- by lives his sister, Claudia, the Nicaraguan consul and a committed Sandinista. Another child, Carlos Fernando, became editor of the FSLN newspaper, Barricada, from which he launched diatribes against his own family. 'Now he's mixed up in something even worse,' Violeta told me with a mixture of horror and despair, 'he's head of the DAP (Office of Agitation and Propaganda).' Only her daughter Cristiana has stayed with her at La Prensa.

They have a meal together from time to time and try not to talk about politics, but the meetings are getting rarer as bitterness creeps in. Violeta's white stucco house is covered with smeared graffiti, left by a Sandinista mob, calling her a traitor and an agent of the CIA. 'How dare they call me a traitor,' she fumes. 'It's the Sandinistas who are traitors, it's they who have bet- rayed our revolution.'

She speaks from experience, since for decades her husband led the resistance against Somoza. Dr Pedro Joaquin Cha- morro, who inherited La Prensa from his father in 1952, fought a battle that went beyond biting editorials and exposés of corruption, and included a failed guerrilla uprising for which he suffered prison and exile. He became the symbol of opposition and it was his assassination in 1978 by gunmen thought to be in the pay of the Somozas that shook Nicaragua out of 50 years of torpor. Somoza became a pariah, lost his grip, and was overthrown in July 1979. 'The detonating spark was my hus- band, the detonator that created unity in this country,' said Violeta. 'If he hadn't died there would have been no war and no victory.'

Shortly before the end, Somoza did what he had always wanted to do but never dared, he sent tanks against La Prensa and blasted the paper into silence. It was a sort of compliment to the Chamorro family for its pivotal role in the insurrection. Weeks later, Violeta took her seat on the revolu-

tionary junta as the political heir to her martyred husband. Those were the halcyon days when businessmen, opposition par- ties, the Church and the Sandinistas were all united in rebuilding the country. It didn't last long, though long enough to consign Nicaragua to the FSLN.

Violeta watched, helplessly, as the Sandinistas took control of the army, the police, the electronic media, the legal system, the schools, and the council of state, and ran them all directly through the Sandinista party, using the junta as a showpiece of pluralism. 'They deceived us all,' said Violeta. 'If I'd known they were mixed up in all this Marxism I'd never have got involved with them in the first place.' In April 1980, she took advantage of a broken foot to resign from the junta. La Prensa, by then in the hands of her combative son Pedro Joaquin, was already sniping at the government for human rights abuses, property seizures, and the indoc- trination of children. At first the Sandinis- tas let it pass, but once armed counter- revolutionaries, supported by the United States, began to attack from Honduras in 1982, censorship on matters of public security was introduced. From there it was but a step to the banning of all criticism. Copies of the censored articles were posted on a board each week in the grounds of La Prensa so that visiting foreigners could see for themselves just how intolerant and capricious the regime had become. But though the Sandinistas did their best to demoralise the paper, sometimes delaying approval so long that an edition failed to appear at all, they let it keep going for the sake of their international image.

Today there is little to be gained by making gestures to the world. Europe and Latin America, which at first lavished aid on Nicaragua, have pulled back as the revolution sours. And the US Congress, once worth courting, has fallen to Presi- dent Reagan's charm. On 25 June the Democrat-controlled House of Repre- sentatives, which has hitherto blocked Reagan's Contra policy, did a volte-face and voted $100 million in fresh funding for the rebels. It was treated as a declaration of war. The next day La Prensa was closed down. 'It is the newspaper of Reagan, financed by the CIA,' said President Daniel Ortega. 'We're not against press freedom, but we're not going to let it be misused for a message of terrorism.'

Many Nicaraguans agree with him. La Prensa has received grants from the National Endowment for Democracy, which is funded by the US government. It has not followed up stories of Contra atrocities and has made ambiguous state- ments about the war that often seem and probably are — a tacit endorsement of President Reagan's policy. And its report- ing has become shrill and venomous over the years. `I used to read La Prensa avidly in the old days,' said an ageing cobbler, `but now it's become a pro-imperialist paper: it's all tied up with the Church, and the rich, and Reagan. It's a pity.'

Critics ask whether it is the same paper at all. In 1980 three-quarters of the staff walked out under Xavier Chamorro, brother of the murdered Pedro Joaquin and himself a director of La Prensa, and formed a new pro-government paper called El Nuevo Diario. La Prensa was left with a small core of conservatives and never regained its former authority or compet- ence. 'Violeta is just a housewife,' says Xavier. 'She's out of her depth in politics. And Pedro Joaquin is a pale imitation of his father. He likes to take up defiant causes, but he doesn't know what he's doing. As a member of the family, it's sad for me to see them so totally misguided.'

La Prensa saw its finest days before the revolution. It has fallen apart like the family that created it, and the country it once served. Its closure is more symbolic than real, for in truth there is no place for a newspaper in the battle that lies ahead. `Let those Nicaraguans who love their country stay in Nicaragua, and let those who love Reagan and his millions go to Miami,' said Daniel Ortega, challenging his enemies to fight. 'Or if they have the courage, join the Contras in the moun- tains.' From now on it's guns that count.

Previous page

Previous page