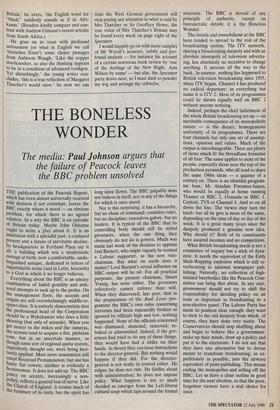

MRS THATCHER'S ZEITGEIST

Timothy Garton Ash enjoys

a German fantasy about modern Britain

DIE ZEIT is Germany's best weekly pap- er. It has published many articles about Britain, notably those by Ralf Dahrendorf. Earlier this year, however, it devoted three prominent pages to perhaps the most ludicrous piece of reportage about Britain that I have ever read. Someone described as 'the young writer Simon Worall', who lives in Germany, here offers us his im- pressions of his native land after long absence.

`After seven years of Conservative gov- ernment one finds a country advancing into the past,' he writes. 'These have been years of an incomparable cultural regress.' From the outset Mrs Thatcher left no doubt of her intention to put the clocks back 100 years.' Every observation, every detail, is then mustered to illustrate this simple thesis. For example, Mr Worall finds a matchbox which depicts a battleship sur- rounded by Union Jacks and the words `England's Glory'. This he considers an `influential talisman of the present, a piece of popular culture from the period after the Falklands war'. Other evidence includes the National Theatre's production of Guys and Dolls in which 'one Depression is shamelessly staged as a nostalgic prepara- tion for the next' and the Royal Shakespeare Company's production of Nicholas Nickleby. `So far as literature is concerned,' continues the young writer, with what one could almost mistake for personal animus, 'the same erosion takes place under the regime of a new junta of Oxford and Cambridge intellectuals around Craig Raine.' This cultural tyrant is described as 'Wortfuhref of a movement called the 'Martial [sic] School'. Raine is alleged to have defined the programme of the Martial School in a pretentious intro- duction to an anthology of Contemporary British Poetry published by `Pinguin Ver- lag'. (The Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry was, of course, edited with an introduction by Blake Morrison and Andrew Motion.) The poetry of this school `reflects a general retreat from reality', and is thus symptomatic of Mrs Thatcher's reactionary Britain.

The centrepiece of Mr Worall's rocky horror show is, however, none other than our own Spectator — 'a British institution like Christmas pudding and the Changing of the Guard'. Our matchless influence is illustrated by the fact that our `Ressortlei- ter "Politik" ', Ferdinand Mount, was for many years Mrs Thatcher's `Chefdenker'. The fact that we have overtaken the New Statesman 'reflects in miniature what is happening in Margaret Thatcher's Eng- land'. There follows an electrifying de- scription of the author's brief visit to our offices.

`As I pushed open the heavy black- painted door of the editorial building of the Spectator in Doughty Street, not far from Fleet Street, and entered a cold damp corridor, almost entirely blocked by a huge cabinet in Victorian style,' writes Mr Worall, 'I had the feeling of stepping back into the past. Closing the door behind me I saw that a hundred years of rain and fog had covered the copper doorknob and locks with blotches and verdigris. I passed on and spied through a doorway a mummi- fied figure in frockcoat and wig, enveloped in cobwebs — but the figure moved, picked up the telephone.' (Well, frockcoat and wig of course — we expect no less from our literary editor. But cobwebs?) Advancing bravely through this chamber of horrors, our hero entered a room 'which looked as if it had last been renovated on the eve of Waterloo'. There he found our deputy editor, 'a young Cambridge graduate cal- led Andrew Gimson'. 'Because I feared the ceiling might collapse at any moment, I began our interview without delay.'

By Mr Worall's account, our deputy editor sat for most of the interview leaning back in his chair, 'his highly-polished black golf shoes [golf shoes?] resting on the desk . now and then he arose and strode up and down — as if to imitate Napoleon —, his hands behind his back, occasionally stamping with his foot to emphasise a point.' At this point, Mr Worall, whom we have begun to suspect of possessing some sense of humour, reassures us that the suspicion was quite unjustified. 'When we spoke about racial problems in Great Britain,' he avers, 'the English word for "black" suddenly sounds as if in Afri- kaans.' (Readers kindly compare and con- trast with Andrew Gimson's recent articles from South Africa.) He goes on to treat with profound seriousness (or what in English we call lierisches Ernst') some choice passages from Auberon Waugh. 'Like the copper doorknocker, so also the thinking appears to be in a condition of advanced verdigris. Yet disturbingly,' the young writer con- cludes, 'this is a true reflection of Margaret Thatcher's world view.' So now we can trust the West German government will stop paying any attention to what is said by Mrs Thatcher or Sir Geoffrey Howe; the true voice of Mrs Thatcher's Britain may be found every week on page eight of the Spectator. I would happily go on with more samples of Mr Worall's accurate, subtle and pro- found analysis — for instance his account of a certain notorious book review by 'one of the darlings of the New Right, Ann Wilson by name' — but alas, the Spectator party draws near, so I must dash to powder my wig and arrange my cobwebs.

Previous page

Previous page