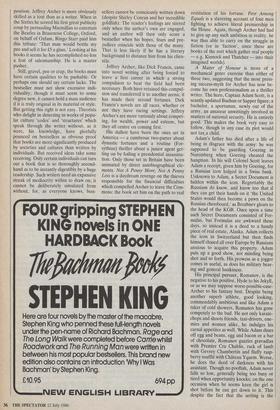

A load of . . . gravel

David Sexton

A MATTER OF HONOUR by Jeffrey Archer

Hodder & Stoughton, £9.95

In a recent Spitting Image programme the puppet Jeffrey Archer was seen ham- mering away furiously at a typewriter. On closer inspection this machine was shown to be equipped with just four letters, C, R, A and P. All the other keys were pound signs.

Was this fair as well as funny? About the cash there is no doubt. In the Guardian report on last year's best-selling paper- backs Jeffrey Archer's First Among Equals came second to Sue Townsend's Growing Pains of Adrian Mole in numbers sold, but, costing 80 pence more, it was easily the top money-maker, clocking up £3,508,144. And the recent television version of Kane and Abel was allegedly seen by more people (13.7 million) than voted Tory in the last election.

But are the books any good? Perhaps the question is naive. In his survey of crime fiction, Snobbery with Violence, Colin Watson said of Edgar Wallace, the Archer of the Twenties, that 'trying to assess Wallace's work in literary terms would be as pointless as applying sculptural evalua- tion to a load of gravel.' If a book is good for three million it is good enough. Yet there are loads of gravel and loads of gravel; some sell, some do not. Why?

It is not altogether a question of what's on the page. For any best-selling author promotion is no less important than com- position. Jeffrey Archer is more obviously skilled as a tout than as a writer. When in the Sixties he scored his first great publicity coup by persuading Macmillan to entertain the Beatles in Brasenose College, Oxford, on behalf of Oxfam, Ringo Starr paid him this tribute: 'That man would bottle my pee and sell it for £5 a glass.' Looking at his books it seems he has accomplished no less a feat of salesmanship. He is a master pusher.

Still, gravel, pee or crap, the books must have certain qualities to be pushable. Or perhaps one should say certain lacks. The bestseller must not show excessive indi- viduality; though it must seem to some degree new, it cannot hold a mass audience if it is truly original in its material or style. But getting this right is not easy. Theorists who delight in detecting in works of popu- lar culture 'codes' and 'structures' which speak through the writer without, as it were, his knowledge, have gleefully pounced on bestsellers as obvious proof that books are more significantly produced by societies and cultures than written by individuals. But received ideas take some receiving. Only certain individuals can turn out a book that is so thoroughly second- hand as to be instantly digestibly by a huge readership. Such writers need an expansive streak of mediocrity within to draw on; it cannot be deliberately simulated from without, for, as everyone knows, best- sellers cannot be consciously written down (despite Shirley Conran and her incredible goldfish). The reader's feelings are stirred only when the author's own are engaged, and an author will then only score a bestseller when his hopes, fears and pre- judices coincide with those of the many. That is less likely if he has a literary background to distance him from his clien- tele.

Jeffrey Archer, like Dick Francis, came into novel writing after being forced to leave a first career in which a strong compulsion to beat the field had been necessary. Both have retained this compul- sion and transferred it to another arena; it has made their second fortunes. Dick Francis's novels are all races, whether or not they have racing settings. Jeffrey Archer's are more variously about compet- ing, for wealth, power and esteem, but they all centre on coming first.

His dullest have been the ones set in America — a cumbrous two-parter about dynastic fortunes and a routine (For- sythian) thriller about a junior agent get- ting on by foiling a presidential assassina- tion. Only those set in Britain have been animated by direct autobiographical ele- ments. Not A Penny More, Not A Penny Less is a daydream revenge on the thieves responsible for the financial difficulties which compelled Archer to leave the Com- mons: the book set him on the path to real restitution of his fortune. First Among Equals is a slavering account of four men fighting to achieve literal premiership in the House. Again, though Archer had had to give up any such ambition in reality, he was thus able to carry on the struggle in fiction (or in 'faction', since these are books of the sort which gather real people — e.g. Kinnock and Thatcher — into their imagined worlds).

A Matter of Honour is more of a mechanical genre exercise than either of these two, suggesting that the most press- ing success-myth for Archer has now be- come his own professionalism as a thriller writer. The hero, Captain Adam Scott, is a scantly updated Buchan or Sapper figure; a bachelor, a sportsman, newly out of the army, an amateur unwittingly involved in matters of national security. He is entirely good. This makes the book very easy to follow, though in any case its plot would not tax, a child.

Adam's father has died after a life of being in disgrace with the army: he was supposed to be guarding Goering in Nuremberg when Goering cheated the hangman. In his will Colonel Scott leaves Adam a receipt, given him by Goering, for a Russian icon lodged in a Swiss bank. Unknown to Adam, a Secret Document is hidden within the icon. Regrettably the Russians do know, and know too that if they can get their hands on it 'the United States would then become a pawn on the Russian chessboard,' as Brezhnev gloats to the head of the KGB. Once upon a time such Secret Documents consisted of For- mulas, but Formulas are awkward these days, so instead it is a deed to a handy piece of real estate, Alaska. Adam collects the icon in Switzerland but then finds himself chased all over Europe by Russians anxious to acquire this property. Adam puts up a good show, not minding being shot and so forth. His prowess as a jogger comes in useful, as does his military bear- ing and general hunkiness.

His principal pursuer, Romanov, is the negative to his positive, Hyde to his Jekyll, or as we may suppose worst-possible-case- Archer to his fantasy best. Despite being another superb athlete, good looking, commendably ambitious and like Adam a taker of cold showers, Romanov has gone competely to the bad. He not only karate- chops and shoots friends, taxi-drivers, ene- mies and women alike, he indulges his carnal appetites as well. While Adam dines off egg and beans, egg and bacon or a bar of chocolate, Romanov guzzles gravadlax with Premier Cm Chablis, rack of lamb with Gevrey Chambertin and fluffy rasp- berry soufflé with Château Yquem. Worse, he does the deed of darkness with his assistant. Though no pooftah, Adam never falls so low, generally being too busy or tired when opportunity knocks; on the one occasion when he seems keen the girl is shot before he can get down to it. This despite the fact that the setting is the summer of 1966, as we are reminded by much laboriously pasted-in period detail: Morris Minors, Mary Quant, the Beatles, new Italian restaurants, petrol at six shill- ings a gallon, Chelsea flats at four pounds a week. One of the more interesting things about the book is how it assumes that from the Eighties the Sixties look a distant land of romance, decency and primordial En- glishness.

Significantly, Romanov's absolutely worst wickedness is that, having de- nounced his own father to the KGB, he abuses the immense patrimony he inherits. By contrast Adam, who gets no cash, has the great aim in life of vindicating his father's honour: 'His heart thumped within his chest as he considered how Pa's life has been wasted by the murmurings and in- nuendoes of lesser men.' Via the icon he eventually obtains another Secret Russian Document with which to quash these Les- ser Men, so affirming his kinship with pater and his values. 'Adam continued to admire him above all men. Sometimes the very thought made him feel strangely out of place in the swinging Sixties.' Most novels deal with people rebelling in some way against their backgrounds. Archer's is the opposite, a positively anti-Oedipal plot; psychologically as well as in every other way the book is completely conservative. Stylistically it is equally loyal to its forbears. Virtually every sentence is a mini-anthology of clichés. The characters express themselves through a very small repertoire of expressions: chins are lifted, shoulders squared, eyes are lowered, mouths tight-lipped, nods are curt, glances sidelong, blinks nervous. The only upsets in this prefabbing come when the parts don't quite fit together. The reader may be justifiably puzzled with the sequence when it is said that 'If Romanov or any of his cohorts come face to face with Scott they'd better remember that he was awarded a Military Cross when faced with a thousand Chinese.' In the plot too there are ill-fitting pieces — including a ludicrous escape from Imprisonment in an embassy — but no matter. All the building bricks are so comfortingly familiar themselves that the reader is unlikely to be perturbed. Similar- ly the serried prejudices about Russians, homosexuals, Americans and the serving and commercial classes are useful rather than offensive. There is so clearly nothing Personal in them.

In short, saying that Jeffrey Archer 'YrItesMeccano prose is praise not critic- IsM; his natural attraction to stereotypes is his prime asset as a novelist. At no stage is the reader burdened by anything complex or original; the book is never so trouble- some as to demand thought. For tired men on trains, weary of things that stay wrong however thought about, a story in which everything comes out right so unthinkingly has its tranquilising attraction. As 'spiritual gin' the book will no doubt go down a treat.

Previous page

Previous page