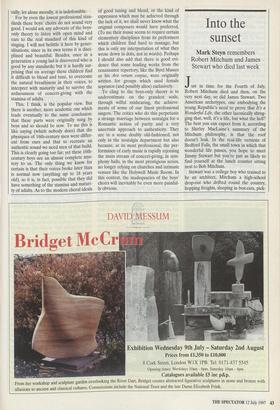

Into the sunset

Mark Steyn remembers Robert Mitchum and James Stewart who died last week Just in time for the Fourth of July, Robert Mitchum died and then, on the very next day, so did James Stewart. Two American archetypes, one embodying the young Republic's need to prove that It's a Wonderful Life, the other laconically shrug- ging that, well, it's a life, but what the hell? The best you can expect from it, according to Shirley MacLaine's summary of the Mitchum philosophy, is that the roof doesn't leak. In the real-life versions of Bedford Falls, the small town in which that wonderful life passes, you hope to meet Jimmy Stewart but you're just as likely to find yourself at the lunch counter sitting next to Bob Mitchum.

Stewart was a college boy who trained to be an architect, Mitchum a high-school drop-out who drifted round the country, hopping freights, sleeping in box-cars, pick- ing up a little dough digging ditches, get- ting jailed for vagrancy, working on chain- gangs ... Stewart — in striking contrast to that other American icon, John Wayne gave up his career, without prompting, to enlist in the Air Force, flying 20 bombing missions and winning a DFC; Mitchum got busted for pot, a scandal so rare in 1948 that Time magazine felt obliged to run a helpful footnote explaining what marijuana was. Stewart was a modest fellow who lived a pleasant, quiet life; Mitchum was set upon by half-a-dozen sailors and was on his way to whipping 'em until his wife stepped in because he was beginning to enjoy it.

The two were physically complementary, too: Stewart was lanky, stringy, gangly, and every inch sucked out of his own chest measurement seemed to have been poured into Mitchum's; Mitchum was sleepy-eyed, Stewart's baby blues were fiercely awake, blazing with indignation, wonder, curiosity. Mitchum favoured economy of spec n; Stewart played men with so much to say their tongues couldn't always keep up either that or he was shrewd enough to realise that those big theatrical speeches needed his trademark stammer to make them digestible. Both men sang, occasion- ally: in Born to Dance (1936), Stewart intro- duced Cole Porter's 'Easy To Love' in a wonderfully light, fragile tenor while strolling with Eleanor Powell in Central Park; a couple of choruses later, Miss Pow- ell is high-kicking around the statues and, for no particular reason, a passing cop is doing impressions of histrionic symphony conductors, and it's only when the picture's over that you realise Stewart's verse and chorus are the only affecting, human moments in what's otherwise a blow-out of generic production-line bombast, culminat- ing in a star-spangled Eleanor Powell rat-a- tat-tatting away surrounded by orgasmic cannons. Mitchum, for his part, made a couple of languorous calypso albums.

Stewart's characters, in the days before William Jefferson Clinton tarnished the formulation, were called Thomas Jefferson Destry (Destry Rides Again) and Jefferson Smith (Mr Smith Goes to Washington) the common man striving, as in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), to live up to high principles, abstract values, concep- tual authority: 'You shoot it out with them and for some reason they get to look like heroes,' says Stewart's Deputy Destry. 'But you put 'em behind bars and they look little and cheap.' Mitchum's Sheriff Harrah, in El Dorado (1966), is unburdened both by such ideological certainty and by Jefferso- nian forenames. His common man is formed by experience.

Think of them as the Bailey brothers: in 1946, in It's a Wonderful Life, Stewart played George Bailey, the role that came to define him; in 1947, in Out of the Past, Mitchum played Jeff Bailey, the role in which his screen persona — terse, cynical, trench-coated — first swam into focus. George Bailey wants nothing more than to leave town and put his life behind him; Jeff Bailey does just that — but discovers he can't escape his past. Fifty years on, asked to conjure up Mitchum, our collective memory still fixes on Jeff Bailey — the tough guy in the fedora with the cigarette dangling from the lower lip. We forget how easily he was stitched up by a conniving, murderous dame, Jane Greer — just as, in Angel Face a couple of years later, even sweet little Jean Simmons did for him. Stewart, on the other hand, acted with wingless angels and imaginary rabbits (Har- vey) but there's nothing sentimental about him — rather a steely unobtrusive tough- ness that cracks through Frank Capra's suf- focating paeans to hicksville integrity.

In the shorthand of television impres- sionists, Mitchum was a pair of frog eyes and an impassive voice; Stewart was even simpler — no 'Play it again' or 'I don't give a damn', just a long, rustic, stuttered `Awwwwwwwwwww% Distilled to such small, precise distinguishing marks, both men seem the very essence of motion pic- ture acting. Yet Stewart played on Broad- way and even Mitchum, after paying his dues behind bars, down mines and in the boxing ring, broke into acting by joining a community theatre group in Long Beach. Each had his persona, yet each, in his best work, effortlessly transcended it. Think of Mitchum in Cape Fear, think of the moment in Rear Window when Raymond Burr, the killer in the apartment opposite, looks back at the chair-bound Stewart, and the watcher becomes the watched — Stew- art was the only golden-age leading-man secure enough to show real fear. Or, if that's too obvious, try The Glenn Miller Story, and marvel at how he captures the bandleader's curiously stiff smile: for as natural an actor as Stewart, there can have been few more awkward assignments than Miller's stiffness. But in such paradoxes as naturalistic stiffness is true, emblematic stardom made: Stewart nice but tough, Mitchum tough but vulnerable. They were wonderful lives. Won't you come home, George Bailey? And Jeff, too.

Ask your teacher to answer your sex questions. My knowledge was gleaned at the street corner, many years ago, and is now completely outdated"

Previous page

Previous page