Giving them the Facts

The Story of Greece and The Story of Rome. By (O.U.P., 12s. 6d.)

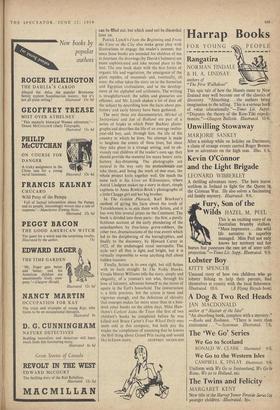

Sia Lives on Kilimanjaro. By A. Riwkin-Brick and A. Lindgren. (Methuen, 8s. 6d.)

The Noble Hawks. By Ursula Moray

(Hamish Hamilton, 12s. 6d.)

Carlotti Joins the Team. By Mike Hawthorn. (Cassell, 10s. 6d.)

Four Wheel Drift. By Bruce Carter. (The Bodlcy Head, 10s. 6d.) 'As the bluebells shake in the breeze, so your tiny feet march to the music of fairy bands . . thus Mary MacGregor, two world wars ago, visualised the young reader of The Story of Greece. Now, after many years' service, this book and its companion volume, The Story of Rome, appear in a new edition, the type-face lifted and the more flowery archaisms pruned back, but still unmistakably dated by the idiom of the writing and of the washy illustrations. It's a pity the re vision wasn't taken further, for as collections of classical myths and legends and historical anec- dotes, both books are valuably comprehensive. More than that, they are written out of affection, not, as so many factual books of the time seem to have been. out of painful duty.

How far the facts-can-be-fun techniques have since been developed can be seen in the rest of the books on the list, and especially in Clarke Hutton's A Picture History of Britain, the book most likely to hit it off with the dungareed, Spock- reared younger set. The brisk, pertinent text runs in and out of the engaging illustrations, their colours almost alight, and takes the reader in sixty-four pages from the discovery of fire to the fireworks on VJ-day. Where the author has been extremely skilful is in selecting the characteristic features that make one period stand out from the next, and in building up a skeletal structure which can be filled out, but which need not be discarded later on.

Patrick Lynch's •From the Beginning and From the Cave to the City also make great play with illustrations to engage the reader's interest; but ' since these books are intended for children of ten to fourteen the drawings (by David Chalmers) are more sophisticated and take second place to the text. The one book deals with the first forms of organic life and vegetation, the emergence of the giant reptiles, of mammals and, eventually, of. man; the other takes the story on to the Sumerian and Egyptian civilisations, and to the develop- ment of the alphabet and arithmetic. The writing is straightforWard; the tables and glossaries are efficient; and Mr. Lynch shakes a lot of dust off the subject by describing how the facts about pre- history and early history have been gathered.

The next three are documentaries. Michel of Switzerland and Jan of Holland are part of a series of bopks in which Peter Buckley photo- graphs and describes the life of an average twelve- year-old boy, and, through him, the life of the country in which he lives. No attempt is made to heighten the events of these lives, but since they take place in a strange setting, and to ob- viously real children of the reader's own age, they should provide the material for many hours' satis- factory day-dreaming. The photographs are natural in the way only the professionals can take 'them; .and being the work of, one man, the whole project knits together well. On much the same tack is Sia Lives on Kilimanjaro, where Astrid Lindgren makes up a story in short, simple captions to Anna Riwkin-Brick's photographs of a little Chagga girl and her big brother.

In The Golden .Pharaoh, Karl Bruckner's method of Bluing the facts about the tomb of Tutankhamen is to mix them with fiction, and it has won him several prizes on the Continent. The book is divided into three parts: the first, a purely fictitious account of the early plundering of the antechambers by free-lance grave-robbers, the other two, dramatisations of the true events which led to the deciphering of the hieroglyphics, and finally to the discovery, by Howard Carter in 1922, of the undamaged royal necropolis. The style isn't all that is light and bright, but it is virtually impossible to write anything dull about hidden treasure.

Finally, fiction in its own right, but still fiction with its facts straight. In The Noble Hawks, Ursula Moray Williams tells the story, simply and elegantly, of a yeoman's son who, through his love of falconry, advances himself to the status of squire in the Earl's household. The conversation is a little precious, but the action is tense and vigorous enough, and the definition of chivalry that emerges makes far more sense than in a hun- dred other books on the olden days. Mike Haw- thorn's Carlotti Joins the Team (the first of two children's books he completed before he was killed) and Bruce Carter's Four Wheel Drift may seem odd in this company, but both pay the reader the compliment of assuming that he knows

the first thing about Grand Prix racing and would

Previous page

Previous page