BOOKS

A liberal of the old school

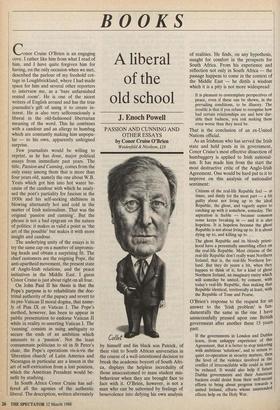

J. Enoch Powell

PASSION AND CUNNING AND OTHER ESSAYS by Conor Cruise O'Brien

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 118

Conor Cruise O'Brien is an engaging cove. I rather like him from what I read of him, and I have quite forgiven him for having, on the only occasion when we met, described the parlour of my freehold cot- tage in Loughbrickland, where I had made space for him and several other reporters to interview me, as a 'bare unfurnished rented room'. He is one of the nicest writers of English around and has the true journalist's gift of using it to create in- terest. He is also very selfconsciously a liberal in the old-fashioned libertarian meaning of the word. This he combines with a candour and an allergy to humbug which are constantly making him unpopu- lar — to his own, apparently unfeigned surprise.

Few journalists would be willing to reprint, as he has done, major political essays from immediate past years. The title, Passion and Cunning, comes from the only essay among them that is more than four years old, namely the one about W.B. Yeats which got him into hot water be- cause of the candour with which he analy- sed the poet's partiality for fascism in the 1930s and his self-seeking shiftiness in blowing alternately hot and cold in the matter of Irish nationalism. That was the original 'passion and cunning'. But the phrase is not a bad epigram on the nature of politics: it makes as valid a point as 'the art of the possible' but makes it with more insight and candour.

The underlying unity of the essays is to try the same cap on a number of unpromis- ing heads and obtain a surprising fit. The chief customers are the reigning Pope, the anti-apartheid movement, the present state of Anglo-Irish relations, and the peace initiatives in the Middle East. I guess Conor Cruise is just about right on all four.

On John Paul II his thesis is that the Pope's purpose is to rehabilitate the doc- trinal authority of the papacy and revert to its pre-Vatican II moral dogma, that name- ly of Pius IX or Vatican I. The Pope's method, however, has been to appear in public presentation to endorse Vatican II while in reality re-asserting Vatican I. The 'cunning' consists in using ambiguity to secure the ends of an ambition which amounts to a 'passion'. Not the least consummate politician to sit in St Peter's chair, the Pope's operations vis-à-vis the 'liberation church' of Latin America and Nicaragua in particular are a lesson in the art of self-extrication from a lost position, which the American President would be- nefit by studying.

In South Africa Conor Cruise has suf- fered all the agonies of the authentic liberal. The description, written alternately by himself and his black son Patrick, of their visit to South African universities in the course of a well-intentioned decision to break the academic boycott of South Afri- ca, displays the helpless incredulity of those unaccustomed to mass student mis- behaviour when they are brought face to face with it. O'Brien, however, is not a man who can be suborned by feelings of benevolence into defying his own analysis of realities. He finds, on any hypothesis, naught for comfort in the prospects for South Africa. From his experience and reflection not only in South Africa — the passage happens to come in the context of the Middle East — he distils a wisdom which it is a pity is not more widespread:

It is pleasant to contemplate perspectives of peace, even if these can be shown, in the prevailing conditions, to be illusory. The trouble is that if you refuse to recognise how bad certain relationships are and how dur- able their badness, you risk making them even worse than they need be.

That is the conclusion of an ex-United Nations official.

As an Irishman who has served the Irish state and held posts in its government, Conor Cruise's most effective dissection of humbuggery is applied to Irish national- ism. It has made him from the start the most destructive critic of the Anglo-Irish Agreement. One would be hard put to it to improve on this analysis of nationalist sentiment:

Citizens of the real-life Republic feel — at times, and dimly for the most part — a bit guilty about not living up to the ideal Republic, the ghost, and vaguely aspire to catching up with it somehow, someday. The aspiration is feeble — because common sense keeps breaking in — and it is also hopeless. It is hopeless because the ghost Republic is not about living up to. It is about dying up to, and killing up to. . .

The ghost Republic and its bloody priest- hood have a perennially unsettling effect on the real-life Republic. Most citizens of the real-life Republic don't really want Northern Ireland; that is, the real-life Northern Ire- land. But they do yearn a bit, when they happen to think of it, for a kind of ghost Northern Ireland, an imaginary entity which will someday be united, by consent, with today's real-life Republic, thus making that Republic identical, territorially at least, with the Republic of Tone and Pearse.

O'Brien's response to the request for an answer to the 'Irish problem' is fun- damentally the same as the one I have unsuccessfully pressed upon one British government after another these 15 years past:

If the governments in London and Dublin learn, from unhappy experience of this Agreement, that it is better to stop tinkering with ambitious 'solutions', and to return to quiet co-operation in security matters, then the level of the violence involved in the conflict of irreconcilable wills could in time be reduced. It would also help if future Dublin governments and their American backers could desist from their well-meant efforts to bring about progress towards a united Ireland, efforts whose unintended effects help on the Holy War.

Previous page

Previous page