ARTS

Art

Mr Bawden's birthday

Giles Auty

Edward Bawden: Line Engravings 1927-29 (Victoria & Albert Museum, Constable Gallery, till 10 April) Today, supposing you get your copy of this issue on Thursday, is the artist Edward Bawden's 85th birthday. The Victoria & Albert Museum is putting on a small exhibition of prints from recently dis- covered plates in his honour. Before view- ing this, I am having lunch with another venerable Academician. Like Edward Baw- den the latter is now slightly deaf but I look forward to our conversation with great pleasure. While many of my colleagues inflame themselves over the supposed neg- lect of young artists, my sympathies are rather more with the old, whom we like- wise seldom seem to cherish sufficiently.

When a boy, I was first taught to paint in oils by an elderly artist who had lost most of his painting hand in the first world war.

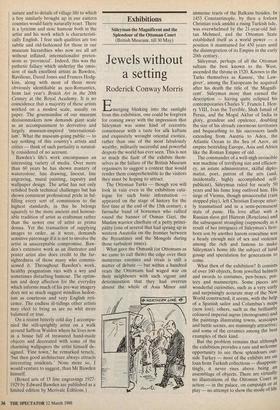

Edward Bawden's 'London Back Garden' Undeterred, he continued to paint left- handed, putting the notch in his remaining stump to intriguing use as a receptacle for pencils and brushes. Principal among my reasons for respecting my seniors is the knowledge that most have seen more than I, suffered more losses and, in many cases, have served this country in time of war. Edward Bawden had an extensive and eventful record as a war artist, being present at Dunkirk, in the Middle East, North Africa and Italy. In passage to the UK from Suez via Capetown, his transport was torpedoed 600 miles off Lagos. After five days in a lifeboat the survivors were picked up by a Vichy French warship and interned at Mediouna. When released by invading Americans, the artist was sent to New York and finally arrived home in an Atlantic convoy, losing all his recent draw- ings in the process. Such a tale may have a moral for many present-day young artists who too often wallow in despair over nothing at all.

Some of Bawden's wartime artist col- leagues were Edward Ardizzone, Anthony Gross, William Coldstream and Carel Weight. Where should we look to find a similarly distinguished group today to re- cord experiences of an active war zone? One might question the utility under such conditions not only of Op, Pop, Minimal, Conceptual and Performance artists but those of a wholly abstract persuasion also. To which of the five winners so far of our four, much-vaunted Turner Prize competi- tions would you personally entrust graphic renderings of, say, the epic evacuation of Dunkirk? (Edward Bawden's moving drawings may be seen at the Imperial War Museum.) Is it some feature of our peace- time complacency and arrogance that artists now take less and less direct interest in the physical world?

Edward Bawden's imagery forms an important component of my own child- hood memories. His paintings and those of his close friend Eric Ravilious, whose artistic life was cut tragically short while serving as a war artist in Iceland, were among the first I saw, by living artists, in reproduction. Bawden's paintings and drawings, whose subject matter centred around the village of Great Bardfield in Essex, where the artist lived for so many years, were distinguished by a response to nature and to details of village life to which a boy similarly brought up in our eastern counties would fairly naturally react. There is a lyricism and stoic humour both in the artist and his work which is characteristi- cally English. I fear such qualities are too subtle and old-fashioned for those in our museum hierarchies who now see all art without inflated, internationalist preten- sions as 'provincial'. Indeed, this was the pathetic fallacy which underlay the 'omis- sion of such excellent artists as Bawden, Ravilious, David Jones and Frances Hodg- kins, along with most of those more obviously identifiable as neo-Romantics, from last year's British Art in the 20th Century' at the Royal Academy. It is no coincidence that a majority of these artists worked on a modest scale, usually on paper. The gourmandise of our museum decisionmakers now demands giant scale as an accompaniment to derivative and largely museum-inspired 'international- ism'. What the museum-going public — to say nothing of this country's artists and critics — think of such partiality is natural- ly considered of no account.

Bawden's life's Work encompasses an interesting variety of media. Over more than 60 years he has shown mastery of watercolour, line drawing, linocut, line engraving, mural painting, tapestry and wallpaper design. The artist has not only relished fresh technical challenges but has shown consistent professional pride in ful- filling every sort of commission to the highest standards; in this he belongs squarely to the more ancient and honour- able tradition of artist as craftsman rather than the newer one of artist as prima donna. Yet the transaction of supplying images to order, as it were, demands sensitive patronage if it is not to involve the artist in unacceptable .compromise. Baw- den's extensive work as an illustrator and poster artist also does credit to the far- sightedness of those many who commis- sioned it. Throughout Bawden's work, healthy pragmatism vies with a wry and sometimes disturbing humour. The optim- ism and deep affection for the everyday which informs much of his pre-war imagery does not so much suggest mindless hedon- ism as courteous and very English reti- cence. The endless ill-tidings other artists may elect to bring us are no whit more balanced or true.

On a recent bitterly cold day I accompa- nied the still-sprightly artist on a walk around Saffron Walden where he lives now in a house full of treasured hand-made objects and decorated with some of the charming wallpapers the artist himself de- signed. 'Fine town,' he remarked tersely; tut then good architecture always attracts interesting residents.' None more so, I would venture to suggest, than Mr Bawden himself.

(Boxed sets of 15 line engravings 1927- 1929 by Edward Bawden are published as a limited edition by Merivale Editions.)

Previous page

Previous page